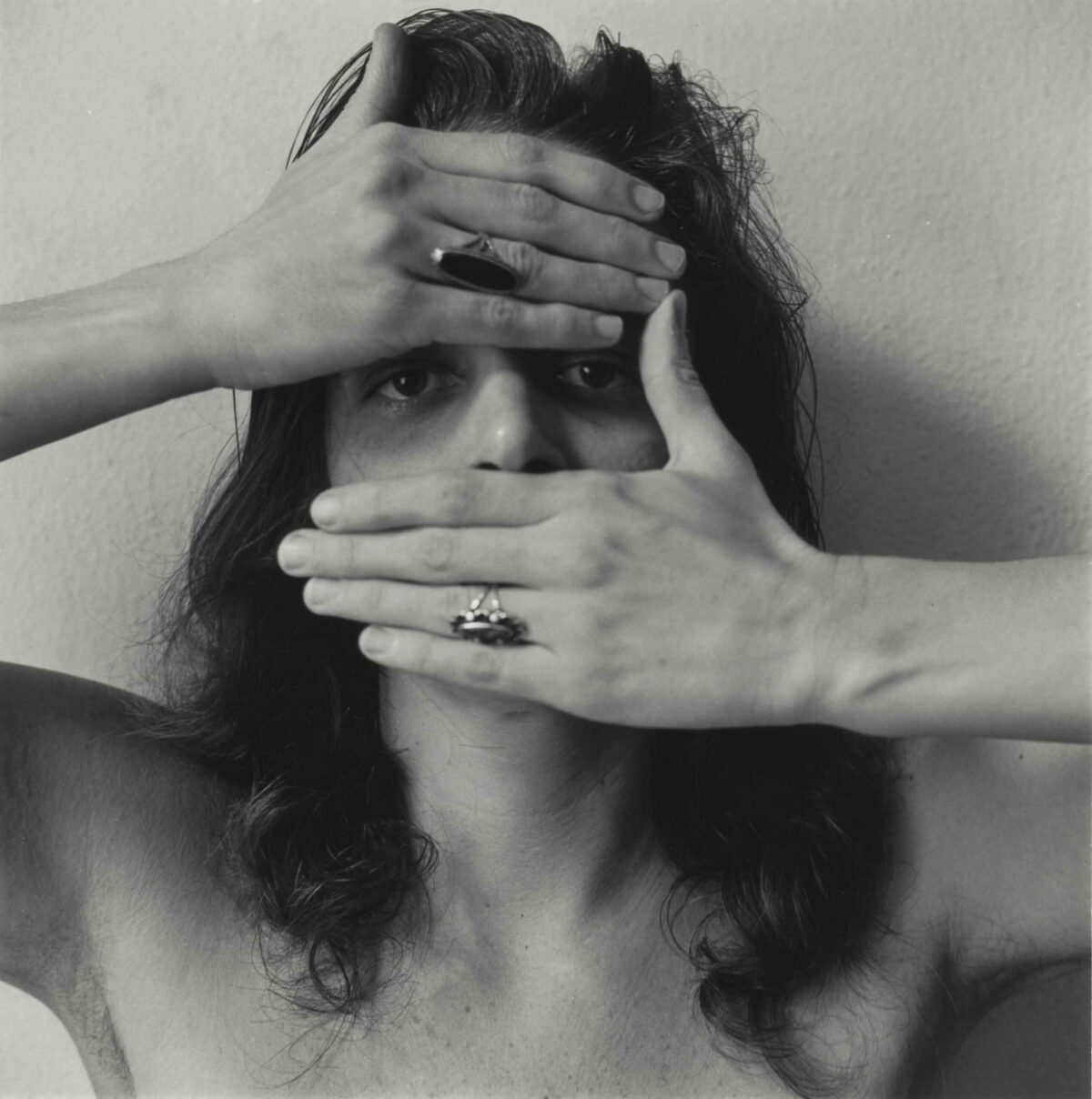

A towering figure in Japanese photography, Issei Suda has received little to no attention in the West. This small, focused show was the first posthumous exhibition of his work since he died last year. The 25 black-and-white prints, shot from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, were drawn from his 1996 monograph Human Memory, which received the Domon Ken Award, Japan’s most prestigious photography prize. Early in his career, Suda worked as a stage photographer with legendary avant-garde theater impresario Sūji Terayama. Under his influence, Suda continued to pursue the mystical side of daily life, taking as his subjects the folk roots of Japanese culture as well as the street life of Japan’s fast-growing urban centers.

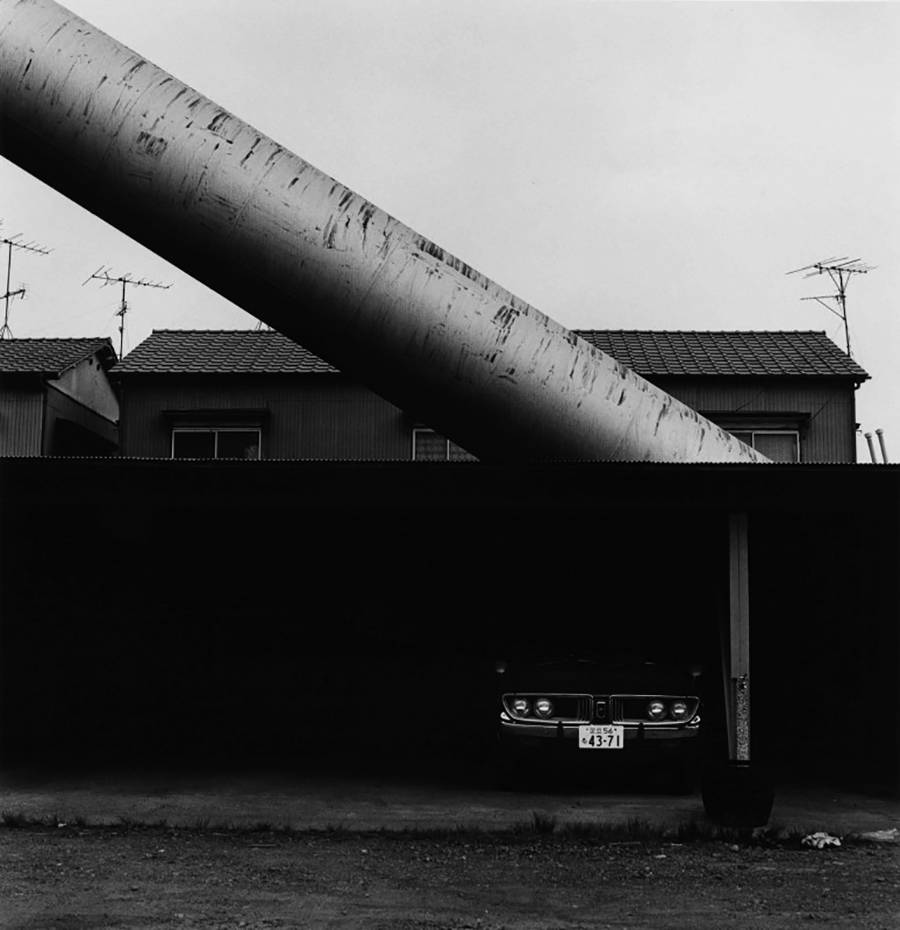

Unlike the artists identified with the Provoke movement – among them Daido Moriyama, Yutaka Takanashi, and Kōji Taki – whose are-bure-boke style (roughly translated as grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus), with its frontal assault on the medium of photography itself, could more easily be read through a modernist lens, Suda was also a precise formalist who carefully constructed photographic spaces to reveal subtle distortions and teasing visual cul-de-sacs. The atmosphere is austere with a deep undercurrent of dislocation and alienation, the result of rapid socioeconomic changes engulfing Japan. But one would not mistake this work for documentary. In a photograph such as Shinden, Adachi-ku, 1981, with its unlikely composition, Suda’s quiet, deliberate style lends a prosaic scene a palpable sense of the uncanny, in part due to his deceptively sophisticated use of the flash. In Gujo-Shirotori-Gifu,1983, a wonderfully Friedlander-esque visual pun, in which a vine twists its way to the apex of a road sign, the lighting is at once too much and not enough, as if it were high noon on a planet with a too-small sun. And much like Atget, as read by the Surrealists, was seen to be an unwitting chronicler of the transformation of aesthetic and social space, Suda’s street scenes reveal a highly ambivalent sense of nostalgia. That the precise associations which might be triggered in a Japanese viewer – of memory and history and hope for the future – can seem elusive to a Western audience does not diminish in the least the quiet visual pleasure of these elegant, austere compositions.