In 2017 or thereabouts, the poet Ross Gay decided to begin a daily practice of noticing, of intentionally paying attention to small things (or large) that brought him delight. He wrote a short essay each day about the things he observed and collected them into The Book of Delights, which was published in 2019. Sandi Fifield Haber’s exhibition at Yancey Richardson Gallery earlier this year brought Gay’s book to mind, because her photographic and multimedia works are the fruits of close and attentive observation. The series is called The Thing in Front of You, as if to underline the fact that a traffic cone, the curve of a white brick wall, a cactus, or a scrap of orange construction netting are all worth noticing and, in her case, photographing. They then become part of an inventive visual vocabulary that she draws on to create these disorienting and delightful photo-based works.

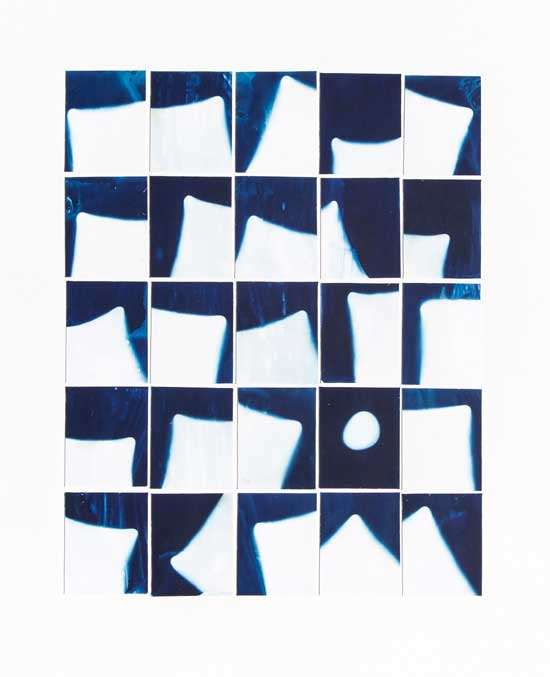

This noticing has long been part of Haber Fifield’s practice. The photographs in Between Planting and Picking, from 2009-10, for example, were taken on and around small family farms, but more often featured throwaway tools like pink and blue plastic buckets or a kinked hose on the grass than fields of crops or pastures. Her studio practice has evolved over time from single images to collage and multi-media works in which she hand cuts her photographs and combines often unrelated imagery as well as – in seven of the works on view – elements like an orange plastic disk, a slender bar of wood, or a slice of Plexiglas. These three-dimensional bits accentuate the geometric qualities of the photographs as well as their already evident focus on materiality.

Certain colors – blue, yellow, orange – echo throughout the works. The yellow of a piece of Plexiglas along the side of one piece draws the eye to the slice of yellow wood placed diagonally in another. A bright ultramarine blue pops up in several pieces. These colors – as well as the sneakered feet that clearly belong to the photographer in one of the photographs – allude to the singular sensibility behind all of these images, to the fact that we’re being made privy to Fifield’s way of seeing, her way of noticing and recombining everyday elements.

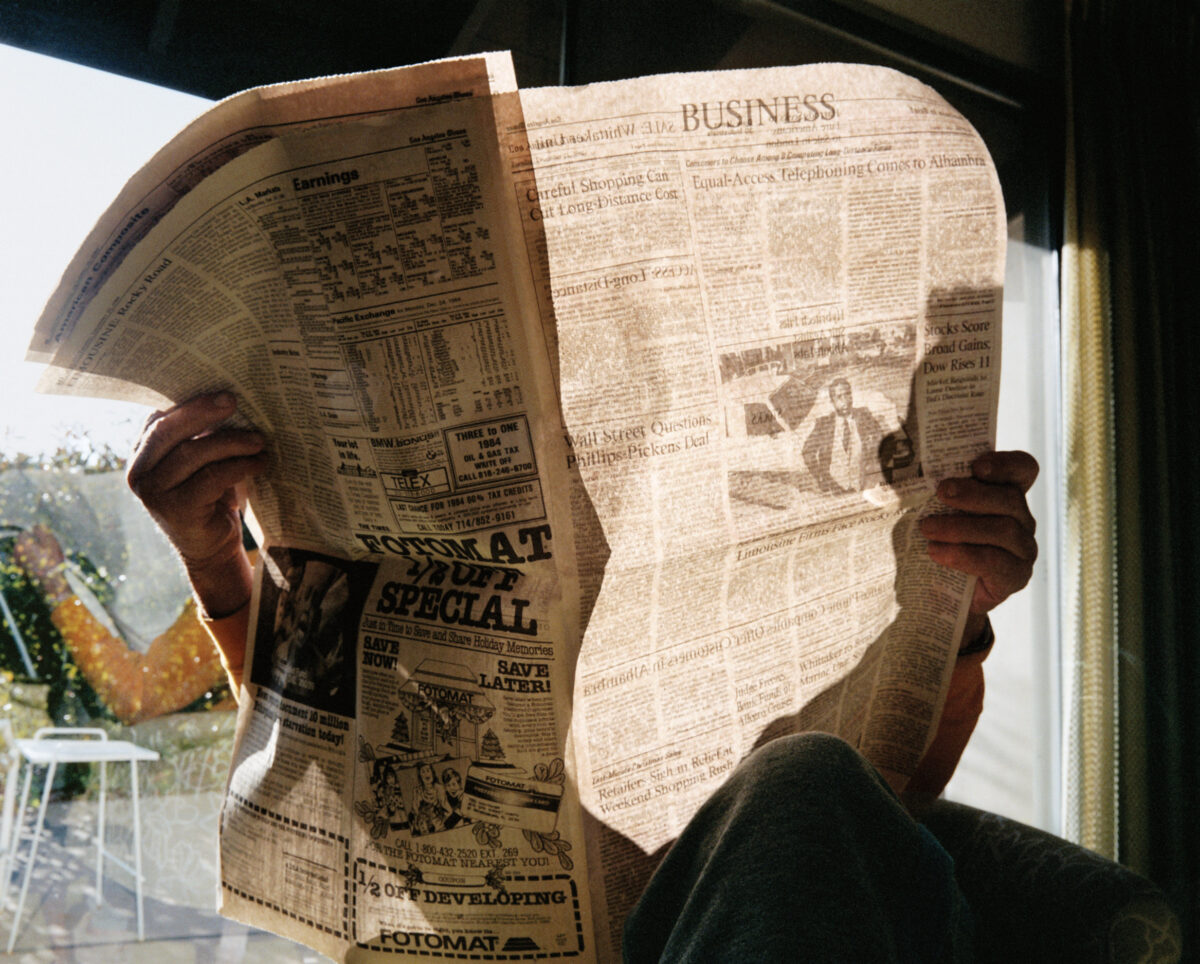

Here and there, a person might be glimpsed in one of her photographs, almost incidentally. A fragment of a face is just visible behind the orange plastic disk in one picture; a small, solitary figure on a bench in another faces away from the camera and also away from the riot of images going in behind him (a stubborn, scraggly plant that’s shoved its way past a striped traffic cone, a wavy cut-out shape in orange, another plant, all floating in a sea of white). They could be read as small reminders of our insignificance, generally speaking, or conversely, of our outsized impact on the natural world, as evidenced by the detritus we leave in our wake (particle board, cement bricks, chain link fencing). In a few images, plant life seems to jockey for space with manmade materials.

But there is also a reading of this work in which it’s not about making meaning of any kind, but rather about the visual pleasure of composition, of playing with spatial elements, with lines and shapes, and with picture plane and perception. It’s about juxtaposing and overlapping – colliding, even – images, as well as cutting around them and allowing them to float free without conventional formats of presentation. In rebuffing conventional ways of decoding a photograph, Haber Fifield’s works invite a richer way of thinking about and looking at them.