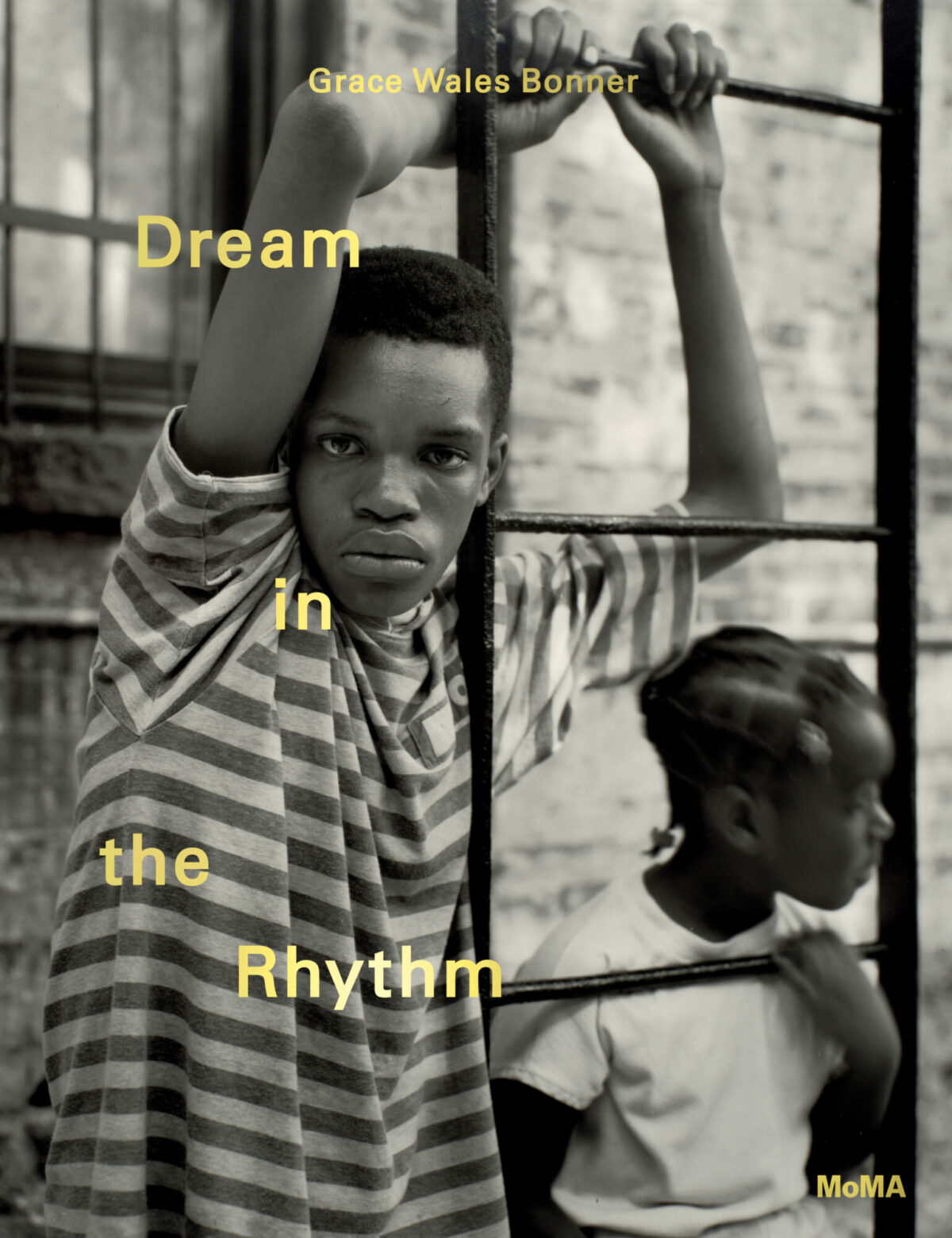

In Citizen, Claudia Rankine’s brilliant meditation on race, she observes, “The past is a life sentence, a blunt instrument aimed at tomorrow.” The two concurrent shows at Steven Kasher Gallery through October 29, photographs of the Black Panthers by Stephen Shames and contemporary color portraits by Ruddy Roye, are, together, a powerful illustration of the truth of that observation, when the same battles continue to be fought more than 40 years later, 150 years later. A photograph in the Shames show, of a boy with his fist raised in front of the New Haven County Courthouse during the trial of Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins in 1970, leads into the Ruddy Rowe show, where the first image shows a woman in a Cleveland street during the National Republican Convention, her fist raised in the same gesture.

Roye, who grew up in Jamaica and lives in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, is a member of Kamoinge, the influential black photography collective. Several years ago, he began walking around his neighborhood, taking photographs and posting them to Instagram, where he now has close to 260,000 followers. Roye accompanies his posts with thoughtful, often lyrical comments, and those are reproduced next to the 20 images in the exhibition. “There is a reason why my words are married to my pictures,” he wrote in an Instagram post (not included in the show) from August 26, 2016. “They are guides, pillars spoken in black and white set to prevent the wayward thinking or behaviors of the yahoos.”

Intimacy and empathy are the hallmarks of the large color portraits (35 by 35 in.) on view, as well as a simmering sense of anger – at the way the people he photographs, mainly African American, often from Bed-Stuy, are either viewed with suspicion, or not seen at all. His subjects include a man helping an older woman cross a snow-covered street, two young black men holding hands at the Gay Pride Parade, and a young woman in green-tinted hair wearing a hand-lettered cardboard sign that says “I hope I don’t get killed for being black today.” In an image reminiscent of something by Saul Leiter, Roye photographed a man, a Jamaican immigrant like himself, from behind a rain-streaked pane of glass, smudges of color, including the red, white, and blue of the flag, reflected in the glass – a partial, elusive sort of American dream.