If there’s truth to the phrase “out of sight, out of mind,” its cruelest manifestation may be the environmental disasters happening all over the planet. Example: in early June, the sky over New York City and Philadelphia turned a murky, choking orange as wildfire smoke from the Canadian interior drifted southeast and mixed with extant air pollution. An ominous if fleeting moment in climate-change-affected weather was reported breathlessly for several days before other pressing news knocked it out of the headlines.

That reportage, and how or if we respond to crises that don’t directly impact us, came to mind when viewing Occidental. Richard Mosse’s latest series, bearing the color-shifted palette for which he’s known (which involves using an infrared film that transforms greens into vivid pinks), invited us to consider the conflicting paradigms that frame our relationship to nature, environmental ethics, and personal comfort.

Starting in 2018, Mosse and his creative collaborators documented environmental crime scenes in Colombia, Brazil, and multiple locations in Peru, including the indigenous Kichwa town 12 de Octubre. Named for the date that Christopher Columbus “discovered” the Americas, the town is located close to swamps, forests, and rivers befouled by oil spills and heavy metals. The malfeasant and unnamed multinational corporation responsible for these disasters mined in regions so remote that many of the most egregious spills can only be located using data retrieved from satellites.

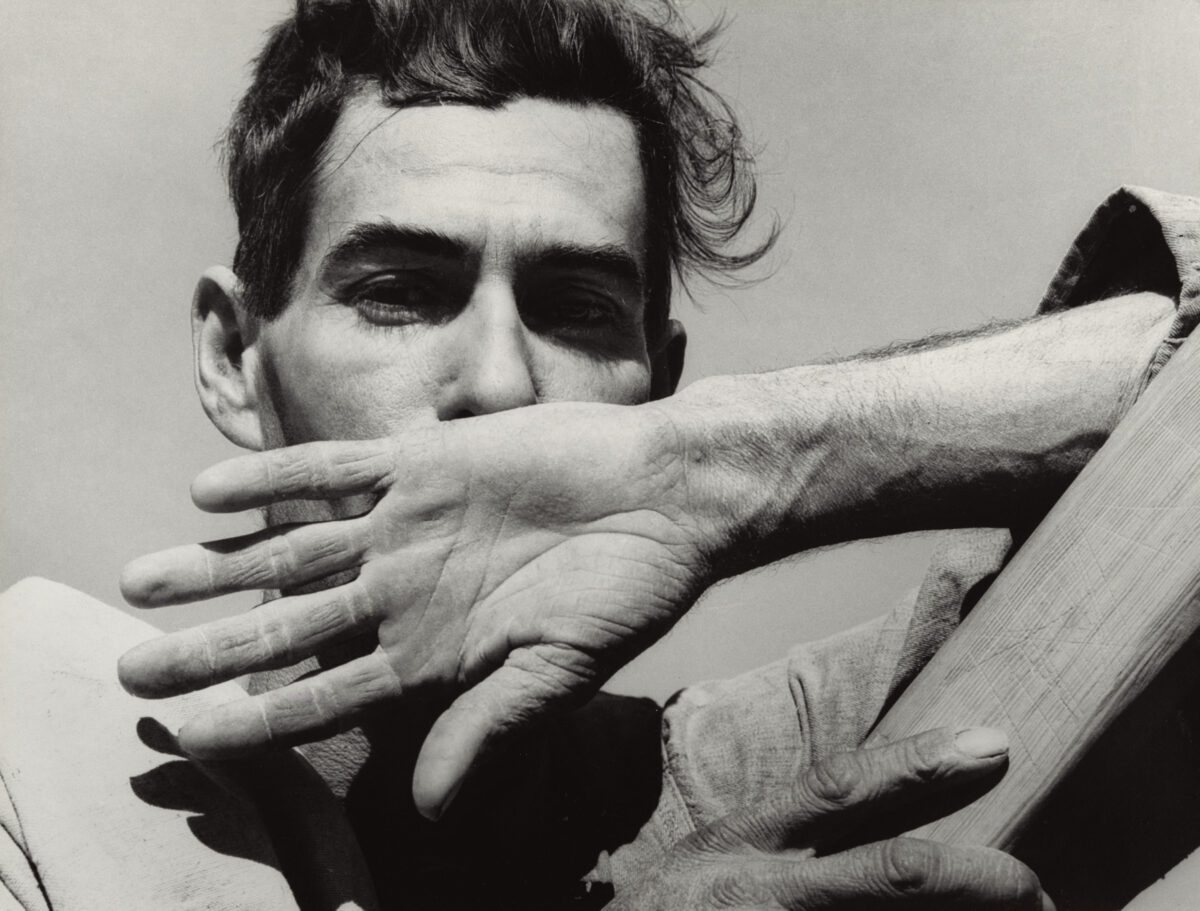

Mosse employed similar GIS (Geographic Information Systems) to locate and eventually access one of those sites. Oil Spill on Kichwa Territory I and III, 2023, deliver immersive views of the dense jungle ecosystem bisected by eroded oil pipes. The lush foliage arching over contaminated water conveys both the potency of natural forms and disgrace at their violation. Captured using drone technology, Abandoned Oil Plant Infrastructure, San Jacinto, Block 192, Loreto, 2022, affords a distant view of environmental catastrophe. From this vantage point, the roads cut through the Peruvian jungle – first to build and then permit service to and from the plant – subdivide the ravaged landscape into what ironically resemble red blood cells clustered on a microscope slide.

Mosse’s photographs from his time in the tropical Brazilian city Belém do Pará emphasize our reverence for domesticated natural forms and offer a bittersweet counterpoint to the wholesale environmental degradation he witnessed elsewhere in the Amazon Basin. Plant in the home of Elaine Aruda, artist, Belem, Pará, 2023, features a potted plant that appears to peak around the corner from its container. I learned, visiting the exhibition, that Mosse regards this and other compositions of house plants as portraits. This framing suggests a consideration of portraiture and its many functions, including as visual connections between past and present, and reminders of life’s brevity and fragility.

In contrast to Broken Spectre, Mosse’s relentless, immersive four-channel film that was installed down the street from Altman Siegel at the newly opened Minnesota Street Project Foundation media space, Occidental’s still images afforded a measured viewing experience. Though dwarfed by the gallery’s high ceilings, the large C-prints ably reinforced the film’s urgent message of widespread ecocide unfolding throughout the Amazon Basin. All of that said, I left the gallery with nagging questions. Does Mosse’s trademark color-shift method aestheticize ecological travesty? Can contemplating ecocide in blue-chip art galleries motivate us to curb the material addictions that require resource extraction and tacitly condone the violence it engenders? If not, what is the point of such large-scale art projects?