It would have been enough to have James Baldwin’s essay back in print, thanks to Taschen Books, an essay that in spite of having been written more than 50 years ago is depressingly, awfully, and inevitably relevant. So little has changed since Baldwin wrote about the casual violence of race hatred, the manipulation of the white working class by oligarchs, and the unthinking pursuit of money above everything. It would have been enough to have Baldwin’s anguished voice in our ear. But we have so much more than that. In 1963, the same year a president was assassinated, Baldwin, a black, gay American writer and the greatest essayist of his generation, together with his high school friend Richard Avedon, conceived a project of words and images that they eventually titled Nothing Personal. Published in 1964, it was meant to be a book that would do something. It would expose America to itself. Baldwin would expose his despair. Avedon would expose his anger and alienation in ways he would never do again, simply by choosing and sequencing pictures he had already shot. Taschen has reprinted the original work in one volume and a new edition in a second volume, with elaborate supporting material and a new essay by critic Hilton Als.

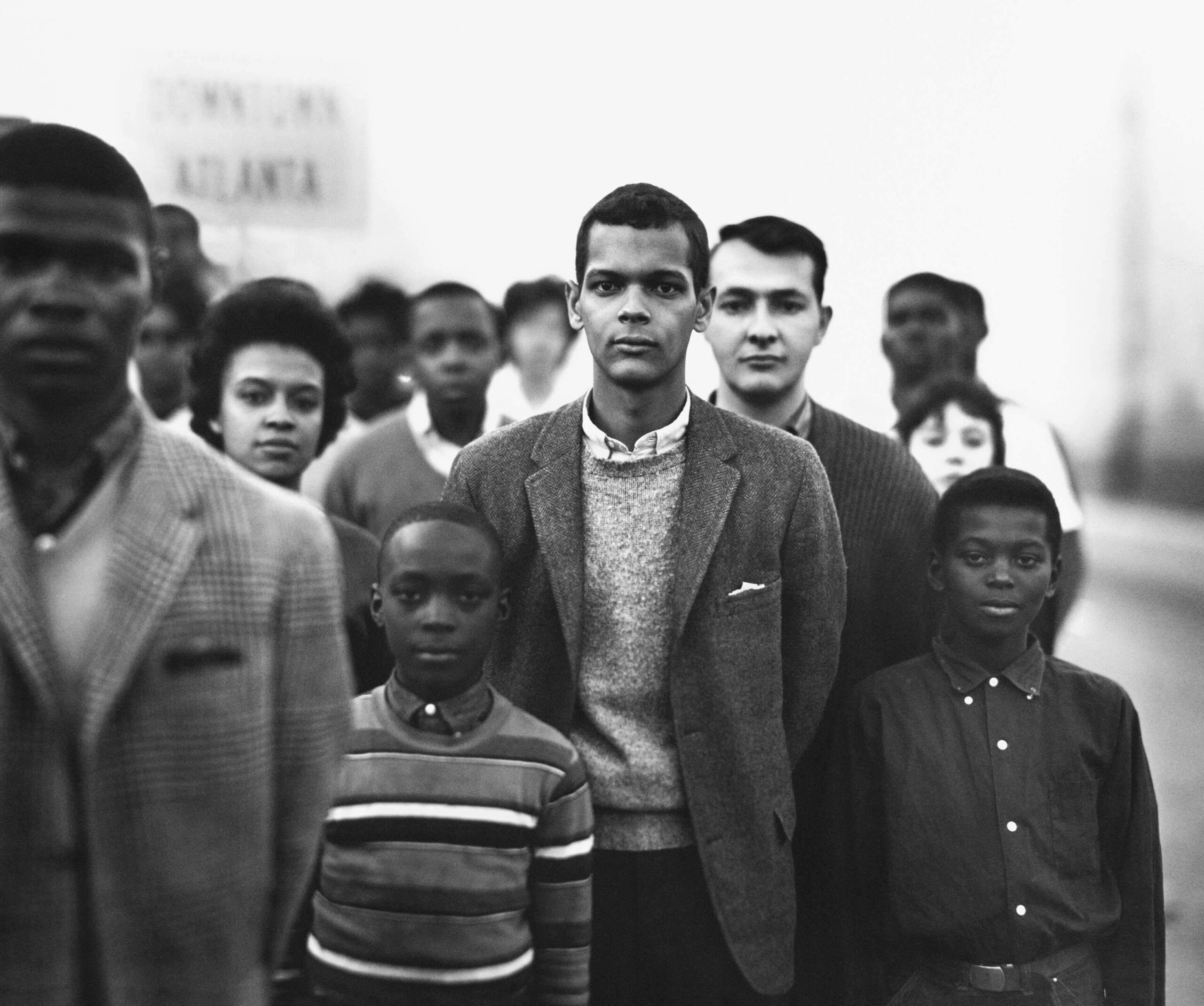

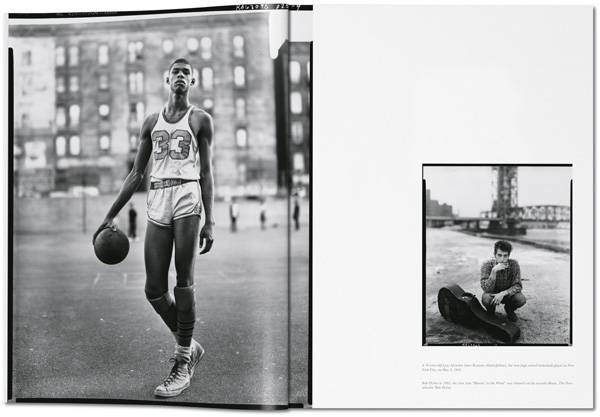

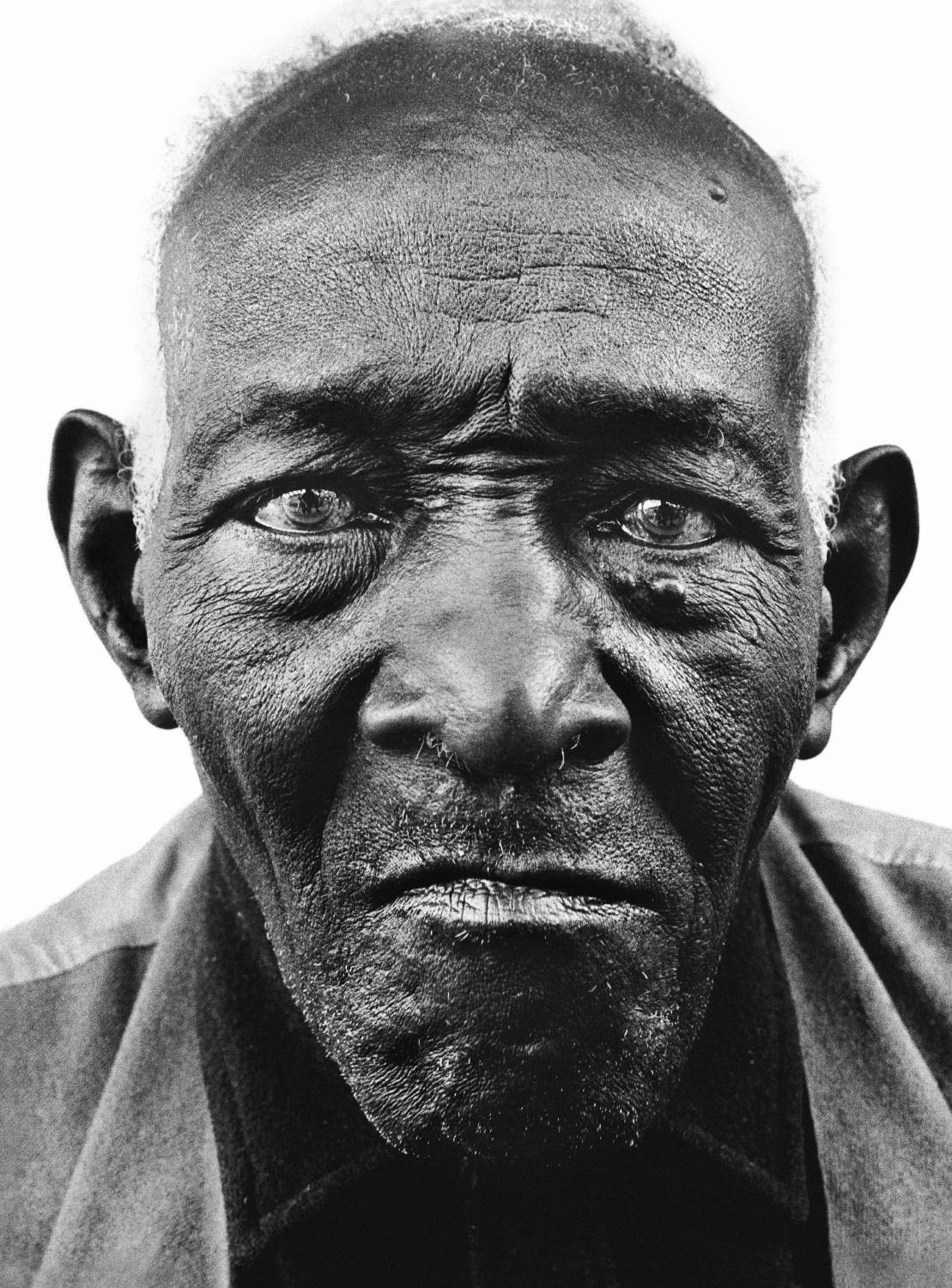

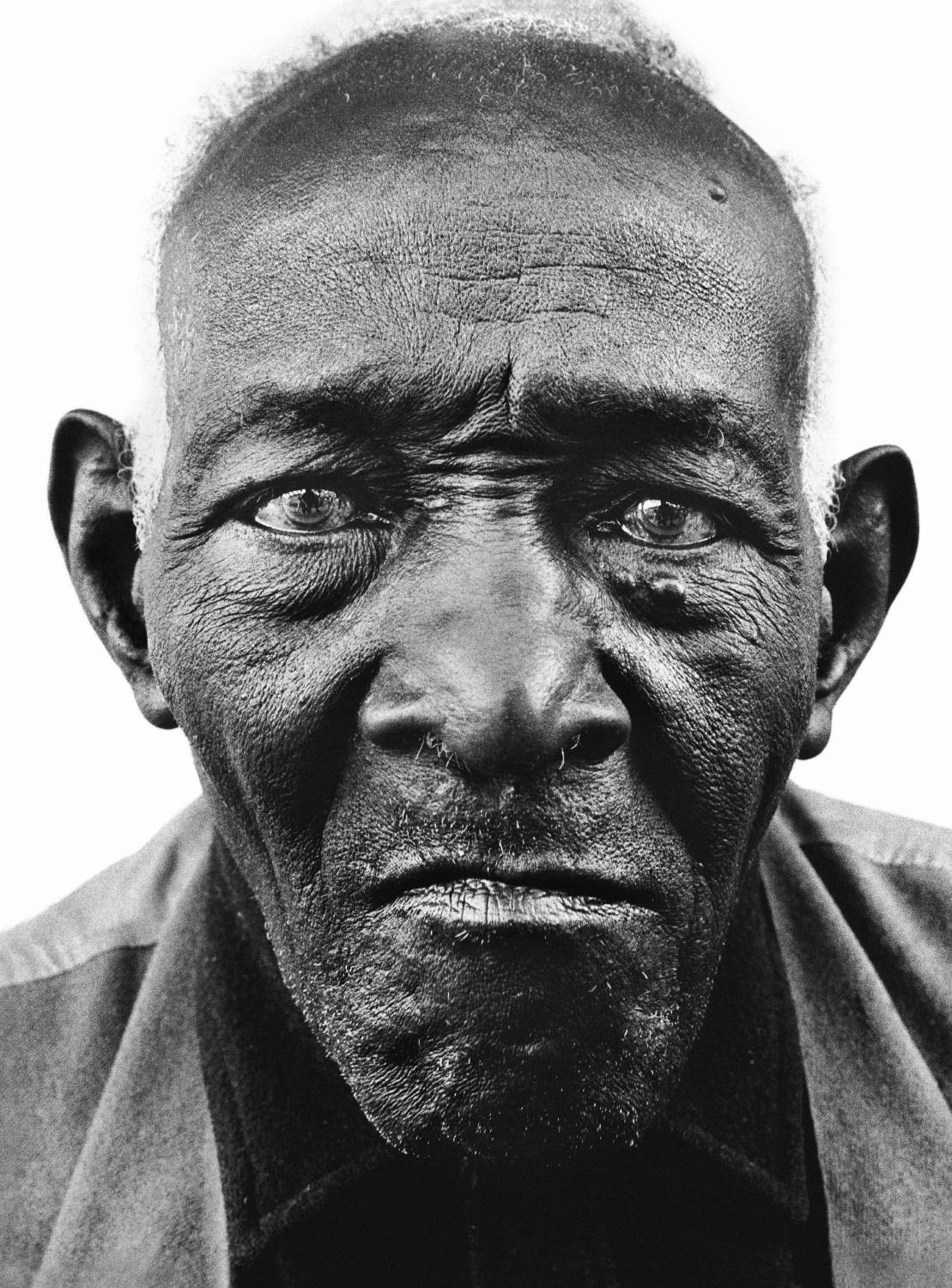

On view through January 13, the exhibition at Pace, organized with Pace/MacGill and the Avedon Foundation, puts all this material on the wall and under glass. It includes everything from the high school yearbook and literary magazine edited by Baldwin and Avedon to candid family shots around the Baldwin family kitchen table to contact sheets from some of the shoots represented by portraits in the book. By 1963, Avedon was still shooting some environmental portraits and – as an extended display at Pace revealed – impactful documentary images. But he had already developed his signature portrait style of large format black and white against a white seamless background, a strategy that often turns his subjects into specimens. We can almost feel them writhe. In the company of Baldwin’s societal soul-searching, the photographs feel so decontextualized they seem at first to be telling a completely different story. High-society wedding celebrants? The Everly Brothers? The now-legendary portrait of an exhausted, pensive Marilyn Monroe and another of the ancient William Casby, born a slave? The contact sheets are important here. With hindsight, we can see Avedon looking and, strangely like Arbus, always landing on the extreme image, the least normal of every session. Avedon manages to make the Everlys appear as malevolent as a pair of contract killers, Dwight Eisenhower as moon-eyed and otherworldly as Borges. As insider-outsiders, both Avedon the Jew and Baldwin the black recognized that American normalcy was a fiction, purchased at the price of coercive violence. That violence is made explicit by the giant image of prizefighter Joe Lewis’s closed fist aimed at the viewer. Powerlessness is met with protest in the only language the country really understands. Nothing Personal was prophetic: “God gave Noah the rainbow sign/ No more water, the fire next time.”