When the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg took the bench to read a dissent, she often wore collars of intricate metal work or copper and gunmetal-colored jewels that glinted against her black judicial robes. It was as though she had donned armor befitting a warrior for justice. Following her death in September 2020, her numerous court collars became icons, appearing in tributes across the country. A few weeks later, photographer Elinor Carucci visited the United States Supreme Court to photograph two dozen collars and necklaces worn during Ginsburg’s illustrious career. The entire photographic series was acquired by The Jewish Museum and is on view for the first time through May 28 (a concurrent exhibition is on view at Edwynn Houk Gallery through February 10).

Given the uniform of judicial robes designed for men, Ginsburg’s sartorial choices were limited to her neckware and she used them to speak to her values (the rainbow-beaded collar in support of LGBTQ+ rights); to honor her relationships (collars gifted to her by her law clerks); and to reflect her passions (the black-and-white jabot from the Metropolitan Opera’s production of Stiffelio). In one particularly moving image, Carucci photographs a collar representing Ginsburg’s family, the interior revealing the hand-sewn words of her husband: “It’s not sacrifice, it’s family.” Carucci makes art from these artifacts, acknowledging their craftsmanship while elevating their personal significance. When viewed together, the series creates a collective portrait of a formidable woman.

Ginsburg was a titan, a lionized historical figure of progressive politics whose likeness has become a pop-culture phenomenon, reproduced as action figures, bobble heads, t-shirts, and tattoos. But to view the exhibition through the lens of celebrity worship would ignore the exceptional curatorial choice by The Jewish Museum to contextualize Carucci’s contemporary photographs alongside Judaica jewelry from the museum’s collection. Standing and wall-mounted cases display 19th– to late-20th-century amulets from the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Europe. These were worn for marriage, childbirth, or other times that called for extra strength, resolve, or ceremony. Similar talismanic properties are seen in Ginsburg’s tactical use of adornment to transform traditionally feminine items into sources of strength. Even her daintiest lace collar is a projection of her power.

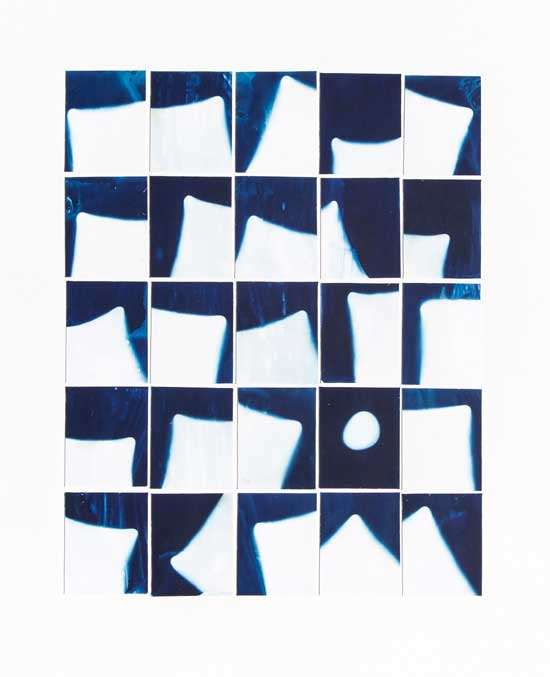

Carucci is known for her deeply intimate photographs of her family, her body, and her experiences with motherhood and aging. She does not shy away from the body’s fragility, from flesh and blood, from the aspects of familial and romantic relationships normally sequestered behind closed doors. Carucci’s work has always relied on visual synecdoche, focusing on parts to tell of the whole – details rather than scenes, facial expressions cropped out of frames, limbs fragmented. In her first foray into the still-life genre, she deftly uses directness and simplicity to achieve a similar result. The collars are presented in a small, true-to-life scale. Photographed straight-on against a black background evocative of Ginsburg’s judicial robes, the collars take on a reverent, emotional quality absent their wearer. RBG Collars: Photographs by Elinor Carucci is an exhibition of two women: both Jews in America, both mothers, both embracing the Jewish principle of tikkun olam (repairing the world) – one through her pursuit of justice, the other through her art.