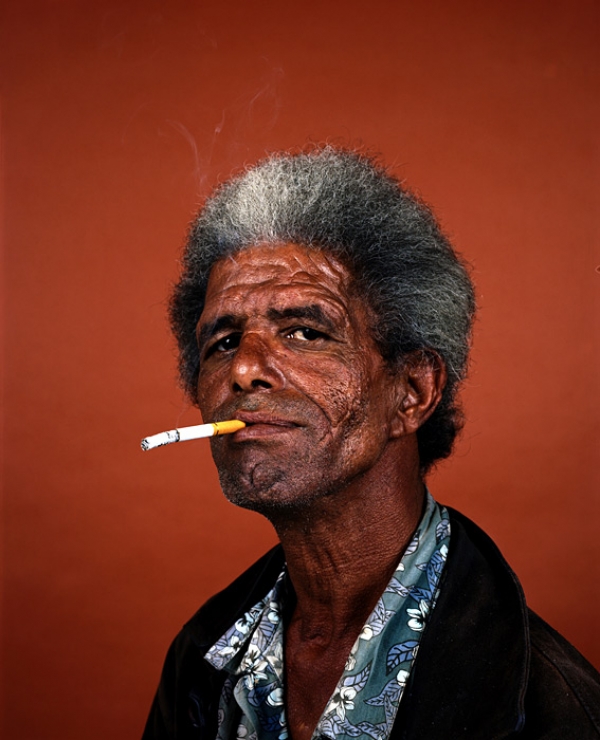

Pieter Hugo’s Kin, on view at Yossi Milo Gallery through October 19, is the photographer’s most restrained and thoughtful body of work to date. Earlier series, such as The Hyena & Other Men, Nollywood, and Permanent Error, lent themselves to visual flamboyance: itinerant performers traveling with enormous “pet” hyenas; surreally costumed actors in Nollywood, Nigeria’s film industry; or apocalyptic images of young people on the outskirts of Accra, Ghana, picking through the debris in burning waste dumps. Critics have denounced Hugo, a white South African who lives in Cape Town, for exoticizing his subjects in these photographs, but the images in Kin are more subdued, illustrating, instead, the web of connections that ties Hugo himself, even loosely, to his countrymen.

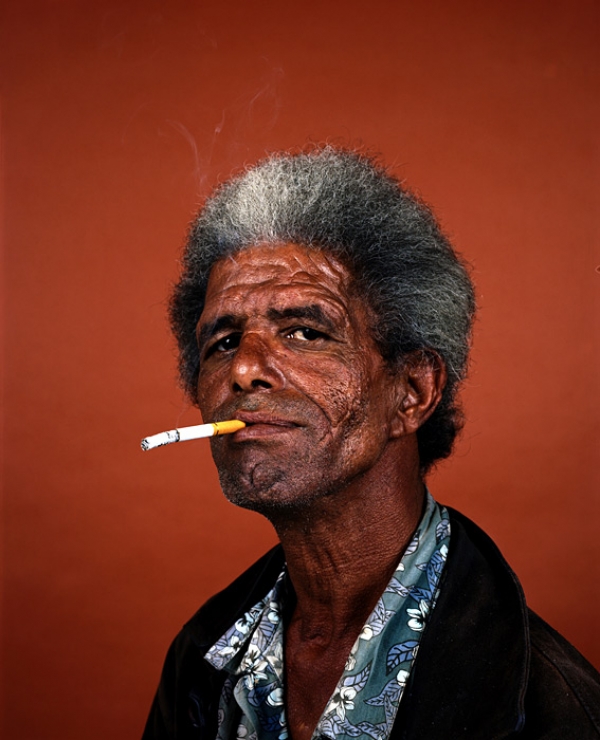

As the title suggests, Kin follows an ever-widening circle of connections and associations, some biological, some simply geographical. There is a photograph of his pregnant wife, naked, as well as a self-portrait of Hugo with his newborn daughter, and a portrait of Ann Sallies “who worked for my parents and helped raise their children.” The personal takes a back seat to the political in other pictures: a picture of a homeless man in Johannesburg, for instance, and a portrait of two men, Thoba Calvin and Tshepo Cameron Sithole, both in ceremonial dress, embracing on a frilly white bedspread. Though this information is not in the exhibition, Calvin and Sithole were married in South Africa, a country with a record of violence toward gays and lesbians, in a ceremony that combined Zulu and Tswana traditions.

The portraits are interspersed with interiors and still lifes – grapes, a gourd, and a dried-out melon on a table against a pockmarked wall; a worn teddy bear slouched in a chair next to a television set – that offer a glimpse of ordinary, day to day life. Further context is provided by an aerial view of Diepsloot, a settlement of shacks north of Johannesburg, near the wealthy suburb of Dainfern. This series, which Hugo created over eight years, laments the legacy of colonialism and apartheid seen in the segregation of townships and cities and people and relationships. It isn’t clear, for the most part, how, or whether, many of the subjects are related to each other: but this body of work would seem to suggest that their specific relationships are less important than their shared humanity.