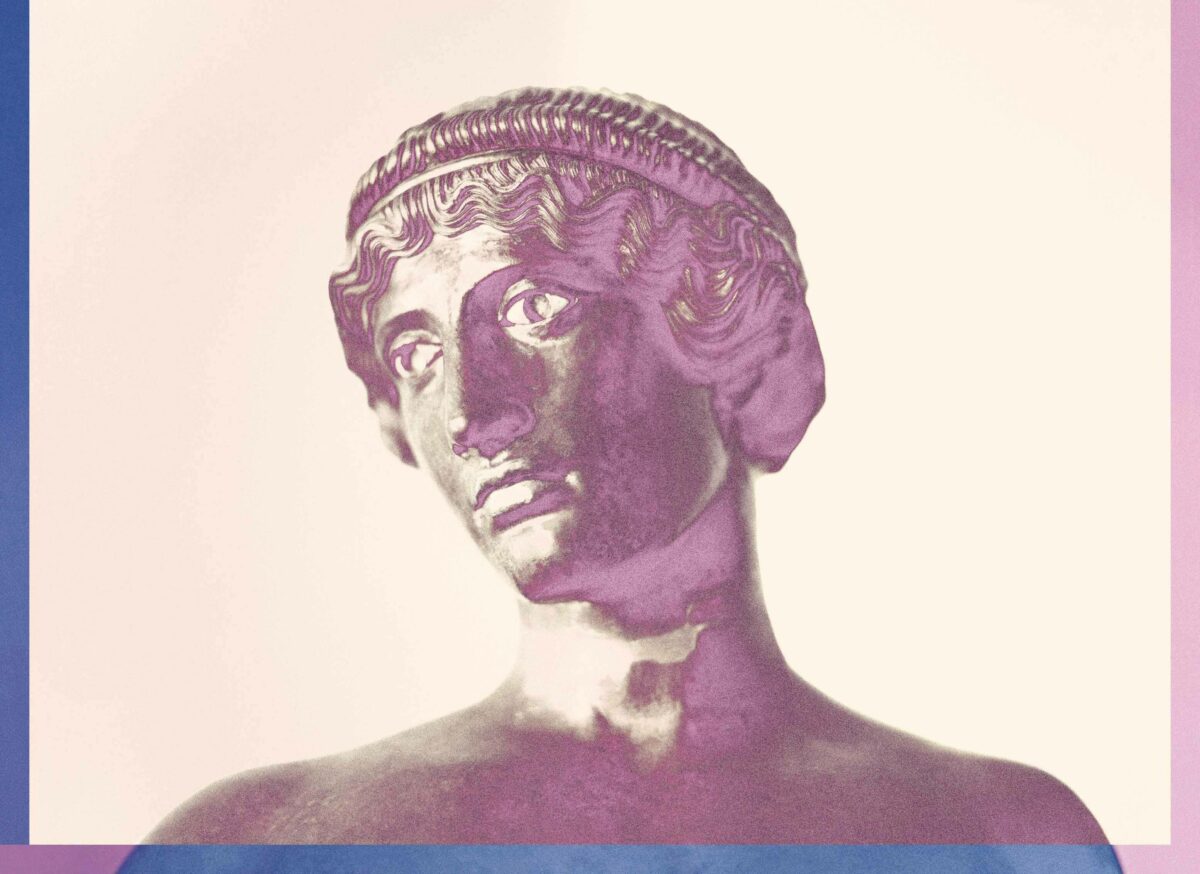

Ordinary Pictures is a thoughtful, occasionally blurred critique of the relationship of art to stock photography. On view through October 9 at the Walker Art Center and featuring work from the 1960s to the present, it makes clear the omnipresent status of the generic image. As curator Eric Crosby writes, “… as an instrument of capital, the stock image is valued not for what it is said to contain or depict, but rather for the multiplicity of potential meanings that can be tethered to it.”

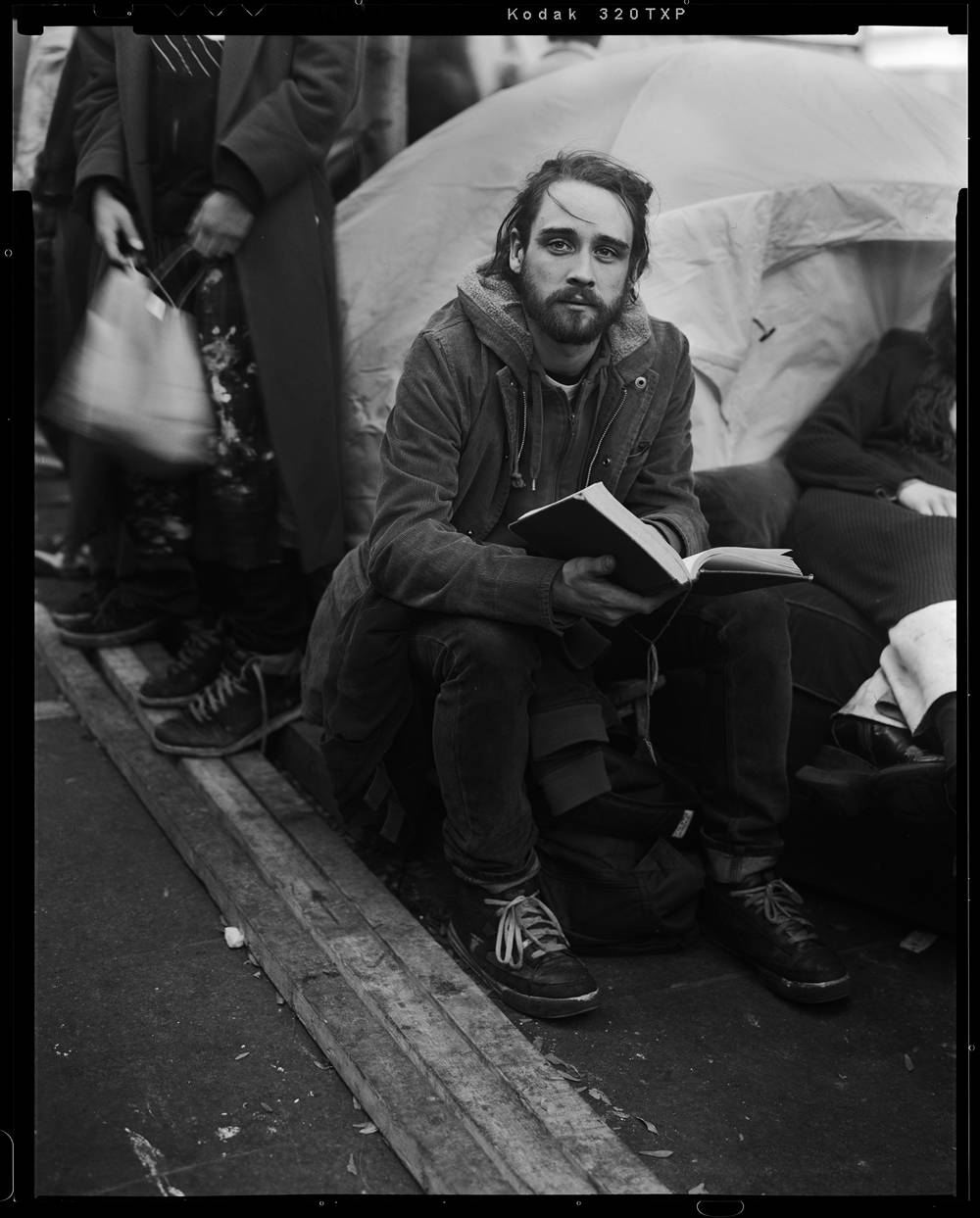

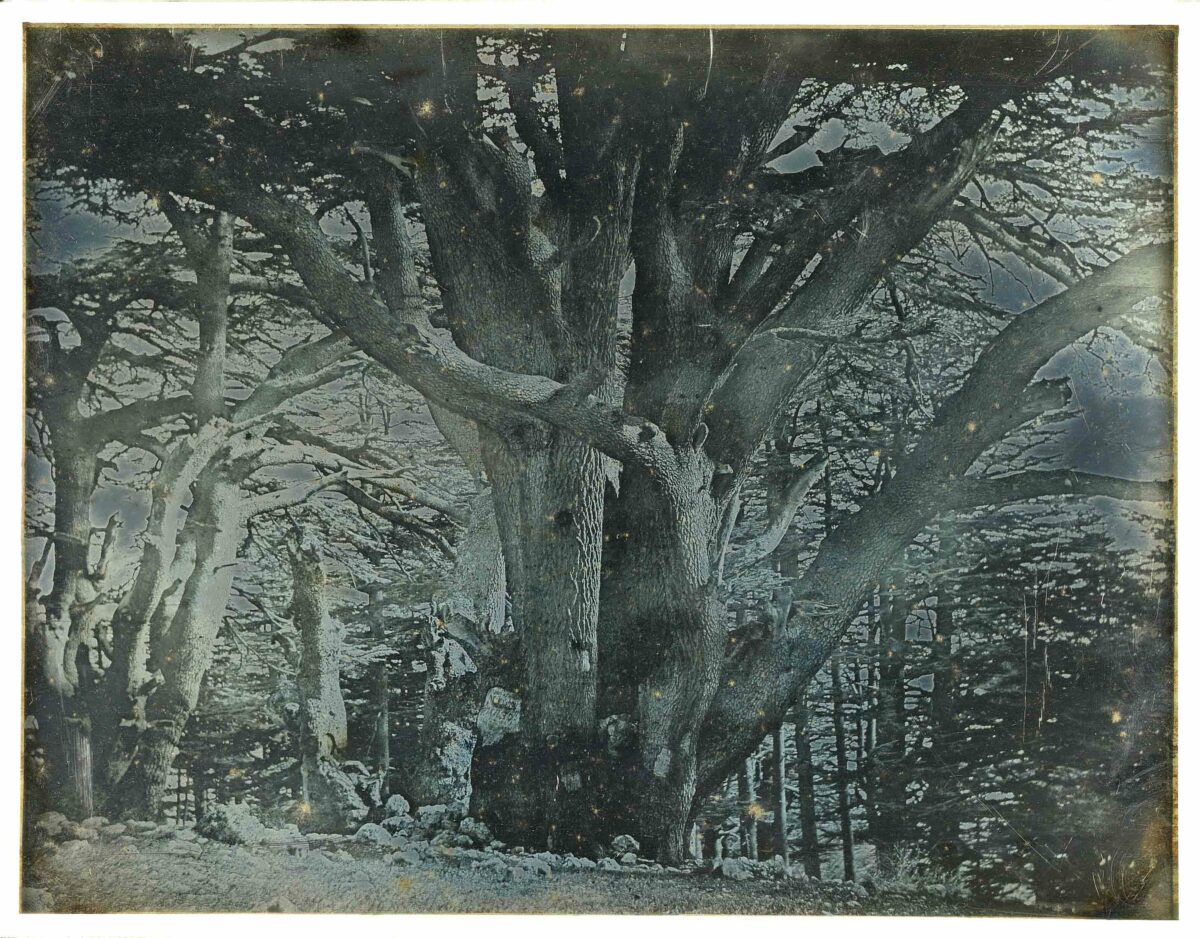

To explicate that premise, the show comprises the work of some 45 artists working across various media platforms. It foregrounds the photograph’s radical trajectory – both in its making and its use – since the 1960s. Where once the photograph was a discrete image made by an individual – a fine artist, commercial artist, or photojournalist – it has morphed into a Hydra-like medium. In the 1970s, corporate entrepreneurs consolidated the proliferation of stock images into archives whose contents were then licensed for use. In the 1980s, Pictures Generation artists exercised strategies of cultural appropriation, leading to today’s onslaught of image production.

The show includes work by such conceptual heavyweights as Hollis Frampton, Ed Ruscha, Louise Lawler and Richard Prince as well as younger artists such as Seth Price, Elad Lassry, and Amanda Ross-Ho. Where Guthrie Lonergan’s video of a sequence of actors playing artists for stock image purposes is the quintessential example of the malleability of generic photographs, other works seem to cloud the curatorial waters. As compelling as it may be as an ironic object, does Ross-Ho’s gargantuan darkroom enlarger, Omega, really support the show’s discourse, or is it simply a symbol of a photographic practice that is largely obsolete?

In the end, the work of older generation artists best supports the show’s thesis, such as Sarah Charlesworth’s 1985 Cibachrome with lacquered wood frame, Tiger, or Sturtevant’s Serpentine Owl Wallpaper, 2013, an expansive wall covering that repeats a video still the artist took from a stock-image website. Crosby makes allowances for his rather slippery curatorial premise by writing that the artists included “may not always incorporate stock photography directly as source material, but their works nevertheless achieve greater meaning and potency when considered against a backdrop of our generic image culture.”