Photography—and its successor, the cinema—is a perfect medium for false documentation, partly due to its audience’s desire to take a photograph at face value. Nothing Personal, a curated exhibition of three artists— Zoe Leonard, Cindy Sherman, and Lorna Simpson—on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through May 1, features examples of biographic trickery from three decades: the eighties, the nineties, and the aughts, highlighting some ways that artists have fabricated notions of gender, class, and race.

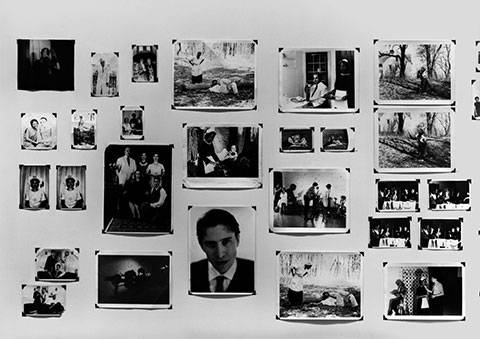

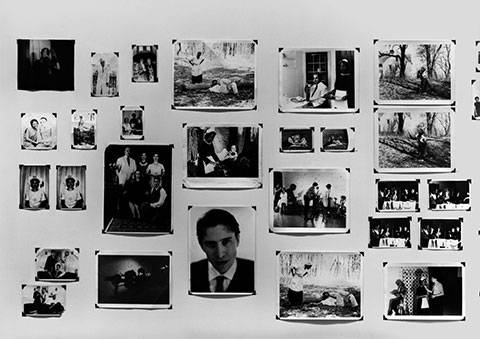

Opening the exhibit is Zoe Leonard’s contrived archive of film stills, publicity shots, and behind-the-scenes peeks that comprise the 82 prints of The Fae Richards Photo Archive, 1993-1996. A sequence of photos introduces the fictional life of Leonard’s invented actress, Richards, a black lesbian who supposedly lived from 1908 to 1973, who performed stereotyped roles as The Watermelon Woman, had an interracial love affair, served in civil rights activities, and finally became a beloved icon of American cinema. The illusion of a turbulent but triumphant life is persuasive due to age-worn prints and typewritten captions on old paper.

But Leonard’s critically lauded “archive” is due for reevaluation. The Fae Richards Photo Archive was once interpreted as a metaphor for racial and sexual invisibility in the artistic community. In interviews, Leonard has said that a black lesbian actress of the civil rights era had to be invented because none had been well documented. But a quick Google search brings up people like Ruby Dandridge (1900-1987) and Carmen Mercedes McRae (1920–1994); not to mention that Richards’s 1930s “Voodoo Magic,” a dance she supposedly performed, looks similar to Josephine Baker’s actual 1927 “Banana Dance.” It is well known that actresses played those roles; another one hardly needed to be created. Twenty years on, Leonard’s pseudo-archive is beginning to discolor to a shade of blackface. The conceptual heroics now seem like a dated fantasy, no longer responsibly tackling issues of representation in mass media.

As for the rest of the exhibit, six (of 70) Cindy Sherman prints from the Untitled Film Stills are on view, hardly presented in a revelatory context. And, Lorna Simpson’s 13-minute, two-channel film Corridor, 2003, of a 19th-century black maid and a 20th-century sophisticate (both acted by artist Wangechi Mutu), manages to be both heavy-handed and conceptually soft at the same time, a rare misstep for Simpson. Rarer still is an exhibition at the Art Institute that fails to bring new light to its otherwise impressive collection.