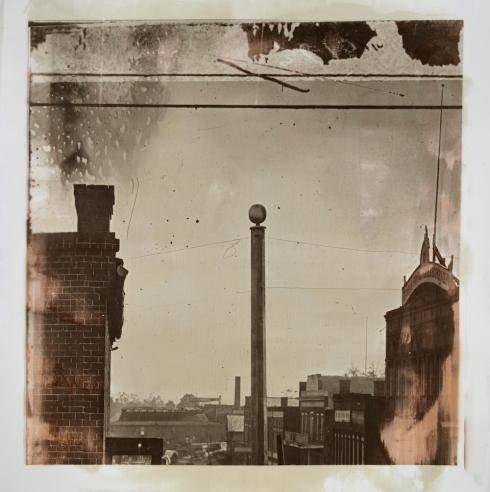

In 1838, Louis Daguerre took a photograph, looking down on the Boulevard du Temple in Paris, considered the first to capture people on film. Two men were fixed on Daguerre’s silver plate because one of them paused long enough to have his shoes shined by the other. Everybody else passed by too quickly to leave a trace, and the men are, magically, alone in the world.

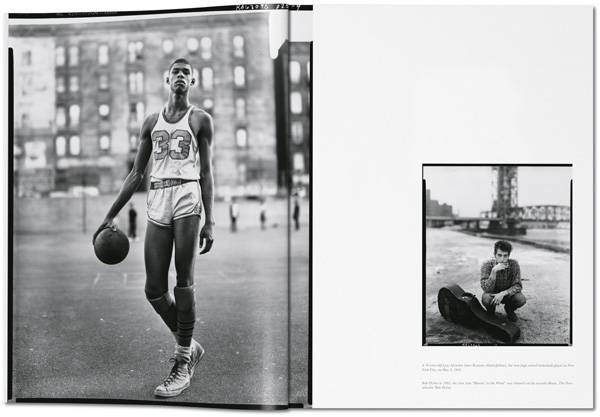

More than most contemporary photographers, Matthew Pillsbury is deeply engaged with the history of the medium and its elemental tools, and the subjects of his long exposures appear similarly enchanted. In his reflective exhibition Nate and Me, on view at the Sasha Wolf Gallery through April 20, the ethereal outlines of Pillsbury and his boyfriend at the time, Nathan Noland, are the only figures in the photographs, pausing long enough to leave an impression on the film, though their movements leave their likenesses blurred. Pillsbury was 30 years old and married when he met Noland in 2004, fell in love and came out as a gay man. Evanescent as their images are, they form a record of their relationship, and of Pillsbury’s then-newfound identity. The fact that the two are no longer together lends the show an elegiac tone.

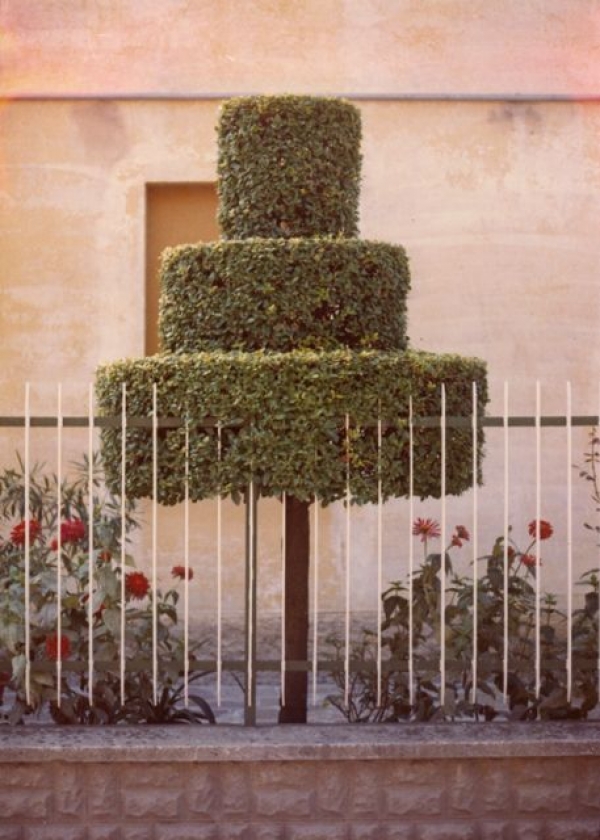

Pillsbury uses an 8×10 view camera and available light, so his exposures can take anywhere from a few minutes to an hour. The settings – a beach, a bedroom, a garden looking over the expansive lights of Hollywood – emerge in rich, velvety black and white, while Matthew and Nate are like apparitions passing by in the glow of a cell phone or television screen.

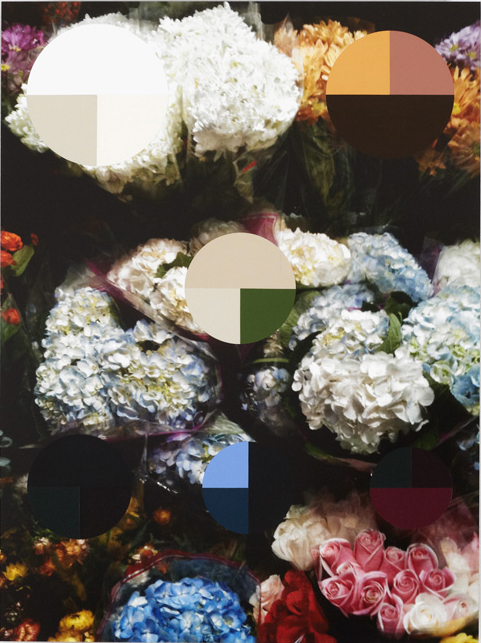

Radiant screens appear somewhere in nearly all of these photographs, like smaller versions of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs of enormous movie screens, luminous and romantic. But Pillsbury’s screens have an ambiguous allure; their glow is a constant presence, even during the most intimate moments.

In HBO’s Rome, the blurred motions of a sexual encounter between Matthew and Nate are captured in the light of the ever-present television. In Nate, Matthew, and Ella at the Pink Cove, the men are more captivated by their cell phones than each other, or the breathtaking scene in front of them. There are many barriers to intimacy, Pillsbury’s 11 photographs suggest, from figuring out who we are and who we love to our misplaced devotion to technology.