Visitors to the RYAN LEE Gallery this spring pulled back the veil draped across the doorway to enter another realm with Anti-Icon: Apokalypsis, eight stunning, shapeshifting self-portraits by Martine Gutierrez. In each, Gutierrez is a different icon: Joan of Arc, a gold chestplate spray-painted directly onto her breasts, slings a wooden sword with the swagger of a thousand dykes; Cleopatra, in kohl eye makeup and a headdress fashioned from a black trash bag, strikes a fierce pose framed by swooping gold Mylar; eight-armed Ardhanarishvara is all onyx limbs, wild hair, and devastating beauty; while silvery Atargatis lies, arms stretched, across rippling shallow waters – part cyborg, part crucifix, she stills the breath.

Tinsel, twine, wire, and wood; paint and the plaster that fashions Mulan’s breastplate and Judith’s severed head; the simple metallic robes worn by a reclining Maria. These are the materials, appropriately austere, that accessorize Gutierrez’s glamorous anti-icons, where dystopian futurism meets the ancient world and classical portrait painting meets celebrity- influencer fashion branding. The simplicity of the materials, limited by the pandemic, only heightens the raw elegance of the portraits. Gutierrez’s intense gaze reappears, deftly transformed, in each photograph, daring the viewer to look away.

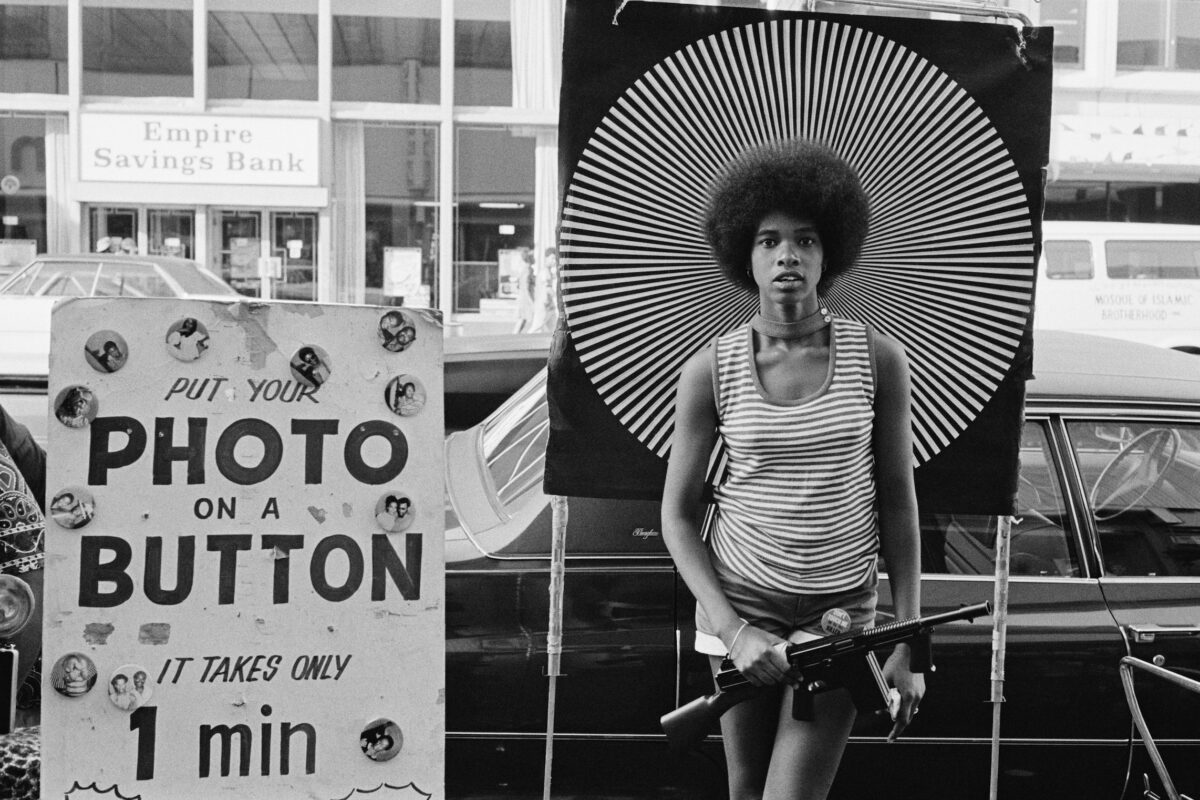

Seventeen anti-icons in total, spanning time and culture, originated from a 2021 Public Art Fund commission that had them displayed on bus shelters across commuter routes in New York, Chicago, and Boston (her nudity shrouded by gauzy veils). In addition to those at RYAN LEE, others are on view at Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco through July 15 and Josh Lilley in London through August 12. Next year, the full collection will be reunited at Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery.

In previous works – like her art book Indigenous Woman, 2018, and her 2022-23 billboard for the Whitney Museum, Supreme – Gutierrez played with the anointment of beauty and authenticity by the advertising industry to explore how women’s identities are made and unmade, circulated and consumed. Gutierrez has been compared to Cindy Sherman, Claude Cahun, Yasumasa Morimura, and Zanele Muholi – all self-portraitists interested in gender and persona – and Anti-Icon is a natural step in the progression of her oeuvre: a vision for the future that both relies on and transcends the past.

With Anti-Icon, Gutierrez goes beyond her characteristic play with branding and celebrity to employ the iconography of ancient texts and corporate symbology, meeting somewhere in between – at once sacred and profane – with the lush exhibition catalogue, the text for which is printed in both English and Aramaic: “When summoning direction in these uncertain times, the chronicles of the divine feminine endure… Femmes of our forefathers – daddy’s deities – perched on the rocks of sirens, fertile with futurity… Neither celebrity nor darling, but a symbol martyred.” Gutierrez’s catalogue text also cites, to humorous, sometimes profound effect, a series of quotes from sources including Disney, the Bible, Nina Simone, The X-Files, Mary Magdalene, and a Gatorade slogan, to reveal the “anti-icon” as a harbinger between the spectacle and poetry of late capitalism and whatever may follow.

This manifesto-cum-scripture-cum-commercial is brought to you by the striking and potent ambiguity of the images themselves. In Gutierrez’s portrait as Guadalupe, zip-tie handcuffs used by police to detain protestors wrap her slick torso like a corset, echoing her spiky crown. Is it irreverent bondage, making due with what’s on hand? A reminder of the police state’s constrictions on each freedom won? Are these end times being advertised, or liberatory new beginnings? In the catalogue, Gutierrez finally offers this definition of the anti-icon: “a representation of both the beginning and the end, prophesied as an omen of rebirth associated with the apocalypse.”