Love, Socrates explains in Symposium, is a form of absence. You cannot desire what you currently possess, and so the desired thing must be absent from your life. Which is to say, to be in love is to be forever striving to grasp what is always slipping away.

Loss, unsurprisingly, abounds in Love Songs, a group show on view through September 11. Conceived as a “a mixtape of songs gifted to a lover” (though you would be unaware of that metaphor without being told), Love Songs, here curated by Sara Raza, was first shown at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris, where it was curated by Frédérique Dolivet and Pascal Hoël. The Paris version of the show – which I also saw – benefitted from the inclusion of mama love, 2008, by Hideka Tonomura, an absolutely fearless and formally audacious work, not on view here, documenting, in erotic detail, Tonomura’s mother’s romance with a new man after she left her husband. Despite the ICP show’s breadth – encompassing photography from 1953 to 2022, from established to emerging artists – loss haunts almost every work, and the best deal with it explicitly.

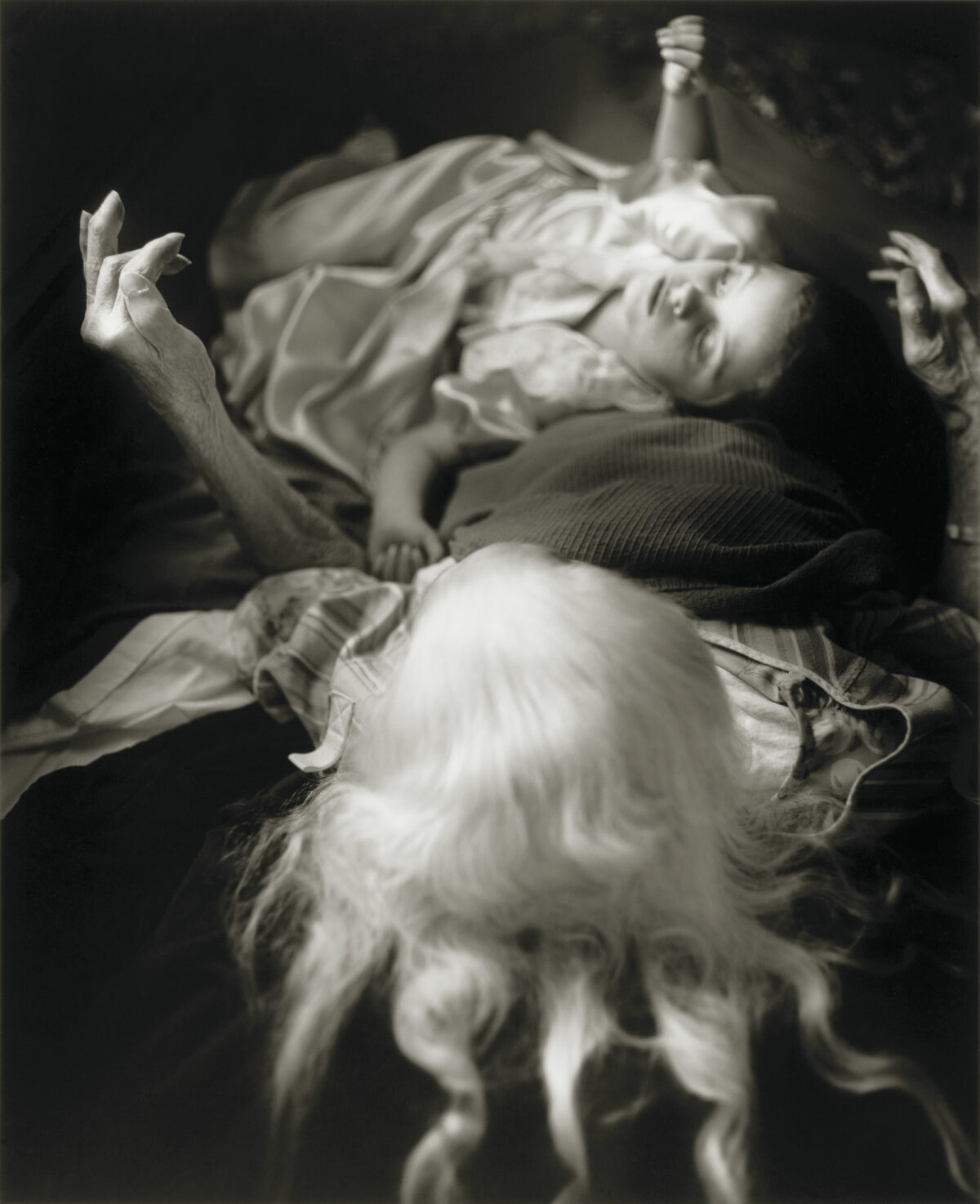

Consider Sally Mann’s Proud Flesh, 2003-09, in which Mann photographed her husband Larry’s physical decline from muscular dystrophy. The work was made with a wet-plate collodion camera, which is only capable of capturing a limited range of light, rendering bright colors as mournful blacks. In addition, the process often creates images marked by physical imperfections – streaks, bubbles, scratches. Larry’s decaying body is mirrored in the marks of decay on the image itself, images which are created on glass plates, fragile and breakable like the body. Larry’s face is obscured in most of the photographs on view, with careful attention paid instead to his increasingly weakened limbs. In Charity of Light, 2008, he is photographed lying on his side, his head out of the frame, his body frail, his scrotum just visible between his thighs, a sign of his waning vitality. In David, 2005, he stands proud and upright, but again his head is out of fame. One gets the sense that despite the piercing tenderness of the series, Mann could not bring herself to photograph Larry the person, but rather confined herself to making a record of his body. His face appears, finally, in Was Ever Love, 2009. He is lying down, his head on a pillow, eyes closed, encircled by a grayish halo from a blemish on the plate and the lighting of the shot.

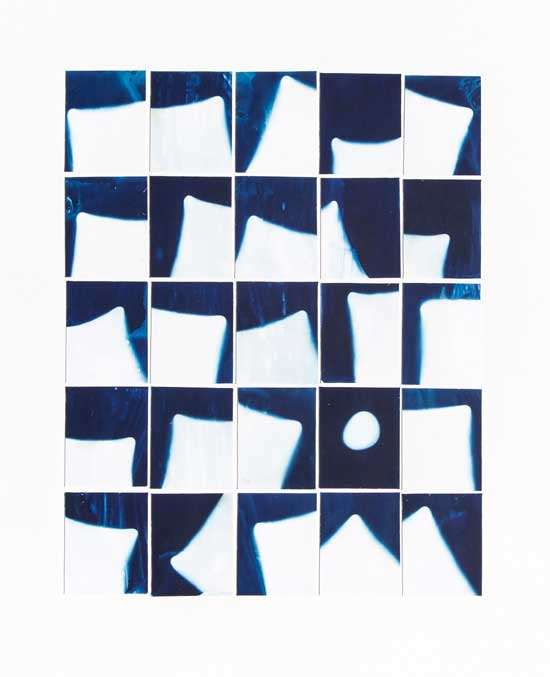

The body is a frequent concern throughout this show. In Iranian-American photographer Sheree Hovsepian’s series of mixed-media collages, the artist cut apart photographic nudes of her sister and placed them in assemblages of wood, string, and paper. The fragmentation of the body emphasizes the severability of body and personhood as well as person and image. Created in the context of the artist’s family’s immigration from Iran to the U.S., the work aims to highlight the different attitudes towards the female body in the two countries. Though operating in radically different political contexts, both contain elements of the same prudishness, censorship, and desire. The collages all evoke a vaguely lunar imagery, both in the color and in the half-moon shapes favored by Hovsepian. The strings that appear to confine or tie down the body allude to femininity with ambivalence – the work celebrates the female form while simultaneously recognizing it as a site of political struggle.

The unabstracted body appears as well, in some cases as a performance. In Leigh Ledare’s Double Bind, one of the highlights of the show, Ledare photographed his ex-wife, Meghan Ledare-Fedderly, at a cabin retreat and convinced her new husband, Adam Fedderly, to do the same, printing both sets of photographs (Ledare’s on black background paper, Fedderly’s on white) and juxtaposing them against one another. In both sets of photographs, Meghan is open and vulnerable, appearing nude or half nude, photographed in playful romps in the forest, reclining in bed, or getting dressed. But there is a palpable difference in the images taken by the two photographers. Ledare’s work comes across as more oblique, less interested in his subject than in her interactions with the environment. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Fedderly’s work is more joyous, more erotic, more focused on the body at the center of the work. The two visions work in conversation with one another. The series plays with the prevalence of the male gaze throughout art history, but it is also about the female figure looking back, looking at the male looking. Meghan, at the center of the work, must have been keenly aware that each pose she took would be shown to the other photographer, laden with meaning. Far from a passive figure, Meghan shapes the images and narratives, emerging as a collaborator in the work’s creation.

The performative aspect of love is literalized in Karla Hiraldo Voleau’s fantastic Another Love Story, 2021, which follows, via narrative text and photography, the discovery that the photographer’s ex-boyfriend, here known only as X, was living a double life – dating two women at once, living and planning futures with both of them, all while keeping the nature of the relationship with the one a secret from the other. The photographs, often featuring Voleau herself, look like candid vacation photos, but are in fact carefully staged. For the series, Voleau used an actor to re-stage photographs of her and X, while also mixing original photographs of the real X wherever his face was obscured. On the one hand, the work references the performance put on by X himself, but on the other, it recapitulates the scenes with a new man as a means of erasing and redeeming the sullied time, this time as art. The sense of loss is palpable, heightened by the “candid” silliness of some of the photographs – even if the images are staged, their referents were not, and the staged happiness was once real, even if the circumstances of that happiness were built on a lie.

A few works are less elegiac – Clifford Prince King’s blissful photographs of queer Black relationships stand out – and though accomplished on an aesthetic level, they lack the fixation on loss that ties the exhibition together. This is, of course, not the fault of the photographer, but a balancing act by the curators, who perhaps cast their net too wide to give the show a greater coherence. Walking into the exhibition you may expect to leave elated, rosy with romance. You leave instead saddened, devastated even. Consider, for example, Nobuyoshi Araki’s work – Sentimental Journey (1971), a series of photographs taken on the photographer’s honeymoon, and Winter Journey (1991), the inevitable corollary, depicting Araki’s trips to his wife Yoko’s hospital room as she died from terminal ovarian cancer. The truth of love, the crux of the exhibition, is contained in Araki’s work: not in any one of his individual images, but in the distance between them.