In 2007, nearly 600 students at the Villa de las Niñas Catholic boarding school in Chalco, Mexico, suddenly lost their ability to walk. In 2012, more than a dozen teenage girls in Le Roy, New York, began experiencing uncontrollable muscle spasms and tics similar to those characterizing Tourette syndrome. Beginning in 2009, several Cambodian garment factories have been the scene of an epidemic among the female workers. All around the world, women were experiencing episodes of fainting, paralysis, tremors, convulsions, tics, and other symptoms. There was no apparent underlying cause.

Catalan artist Laia Abril has taken a closer look at this phenomenon, which affects mainly groups of women. Her work, which was nominated for the Prix Elysée in 2018, is part of a larger project that she began four years ago titled A History of Misogyny, in which she considers abortion, rape, feminicide, and menstruation.

This series started with an article reporting that a group of teenage girls had suddenly fainted in a school in Nepal. Abril first thought it was an isolated case, but she eventually discovered that there were hundreds of other similar cases, and not just in Nepal. There were cases all of the world of what was commonly known as “mass hysteria.”

The title of the exhibition, On Mass Hysteria, deliberately echoes the misogynistic prejudice surrounding hysteria, framed as a “women’s disease” and often used to diagnose what is seen as disturbing behavior. Behind this supposed disorder lies a method of controlling women. A diagnosis of “hysteria” has long been a convenient way for men to negate women’s political awareness. Virginia Woolf and several British suffragettes were diagnosed as hysterical.

On view through October 1, the exhibition details the three cases that took place, respectively, in Mexico, Cambodia, and the United States. Archival material displayed on the walls indicates that the different cases, continents apart, have some common triggers: intense stress, rejection, or an inability to express one’s thoughts or emotions. “Perhaps what’s making them ill is society’s oppression,” speculated Abril. These women are not allowed to protest, so their bodies perform an act of resistance.

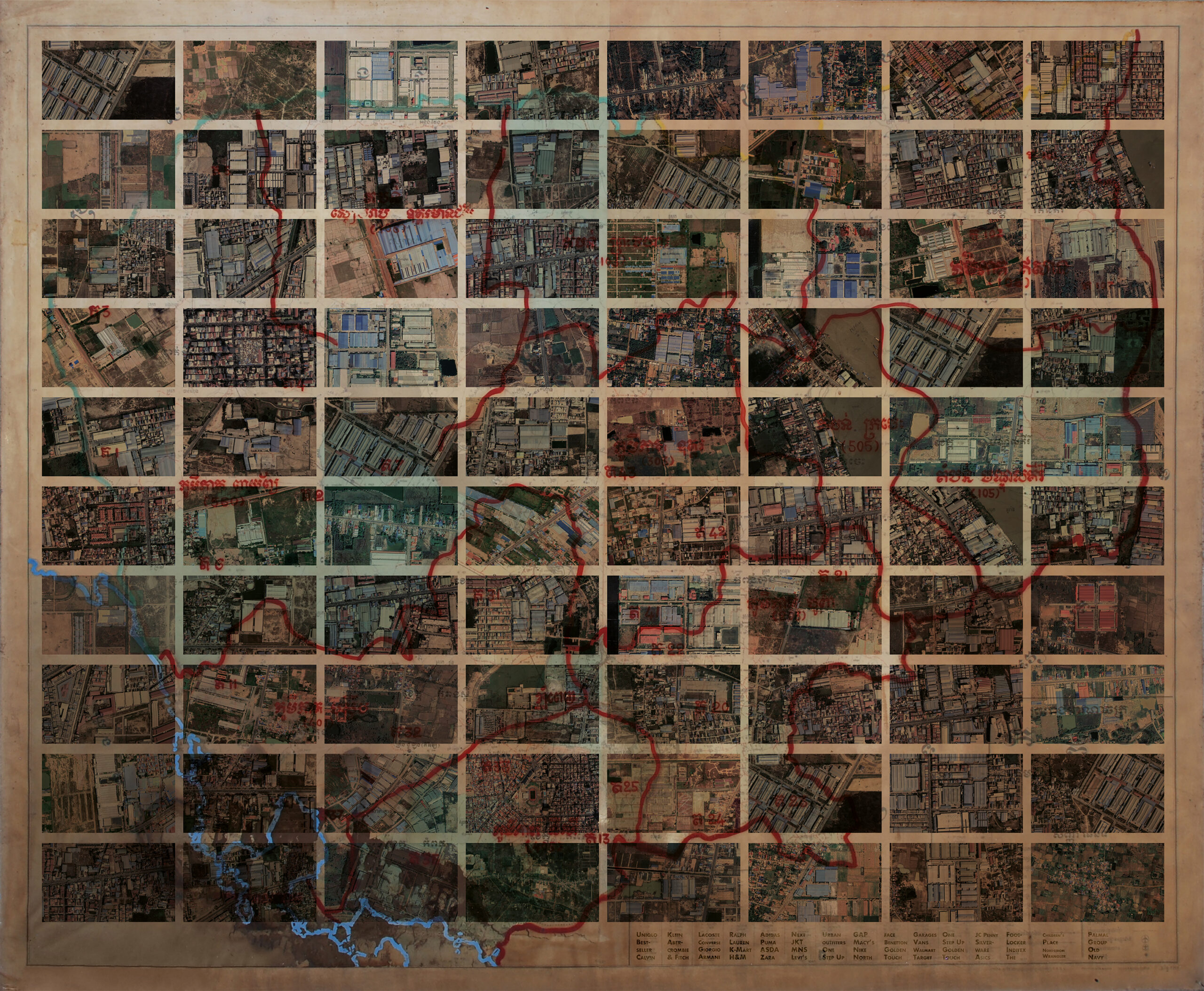

On Mass Hysteria takes a hybrid approach, crossing viewpoints, eras, and borders, as Abril’s research into mass hysteria led her to investigate the Cambodian genocide from the 1970s. The photographer used hundreds of satellite images and pinpointed the factories where thousands of factory workers inexplicably collapse every year. Many of the factories were built on mass graves dating back to the genocide perpetuated by Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge regime. According to psychiatrists and sociologists, these women were reliving this transgenerational pain through episodes of psychosis.

“Almost seems like they pretend to be sick;” “They faint because of their feelings;” “They wear too much makeup:” the sexist discourse propagated by the media appears in large red letters over archival images of these psychogenic episodes in factories around the world. The lack of a physiological or biological explanation has generated a divided response: either we say that women are faking it or imitating each other, or we take hysteria as a kind of diagnostic dead end, grouping together diseases linked to women’s physiology or mental problems. Ignored or downplayed by society, these phenomena feed the stereotype of female vulnerability.

The final part of the exhibition features Mass Protest, a video installation that pays tribute to women around the world who have protested against social injustice. In a dimly lit room, three screens project some 100 clips, each a few seconds long, of women’s revolts that have taken place over the last decade. Meanwhile, three monitors placed on the floor run images of women in fits of “mass hysteria.” The installation turns the stigma on its head, reappropriating the word and giving it new meaning.