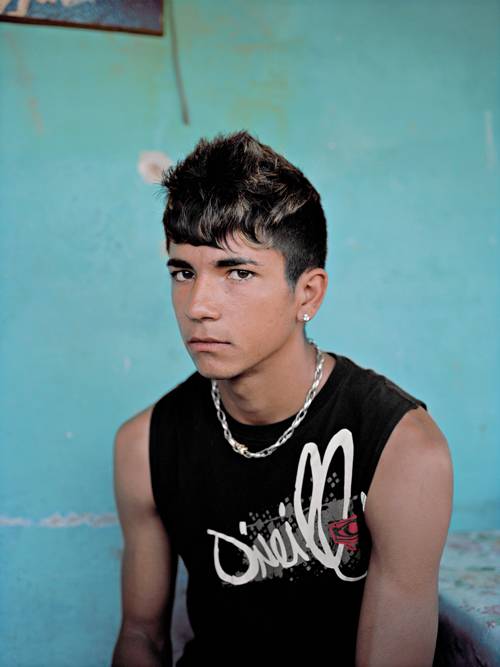

Evolving aesthetic mastery and a desire to portray human individuality are robust notes in Judy Dater: Only Human, on view at the de Young Museum through September 16. This tightly curated exhibition of the Bay Area artist’s work is the first in 20 years to consider the breadth and depth of her five-decade career. The stages of that career are here portrayed in a graceful arc that includes the sitters and situations that drew her attention and the path she found for herself in a professional world that is hostile to women.

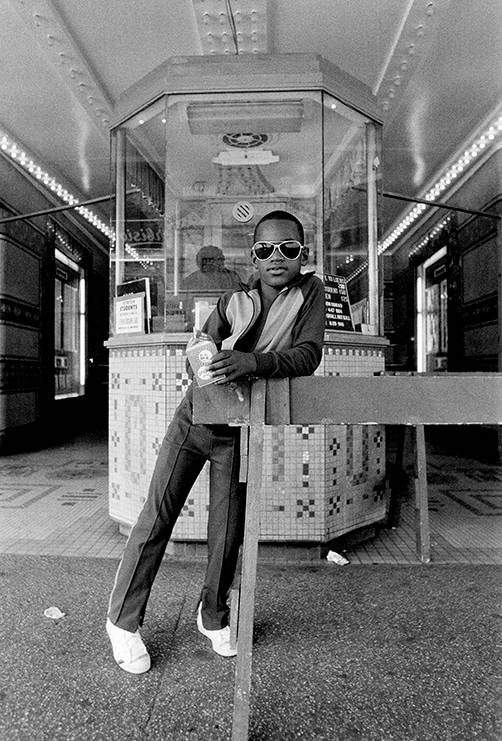

Growing up in Hollywood, Dater spent time at the Clinton, a now-defunct local movie theater on Western Avenue that her father owned and operated. It was there that her interest in the visual world was sparked and later nurtured at San Francisco State University – where she earned both a BA and MA – and through her association with Group f/64 members, including Imogen Cunningham, who became a friend and mentor.

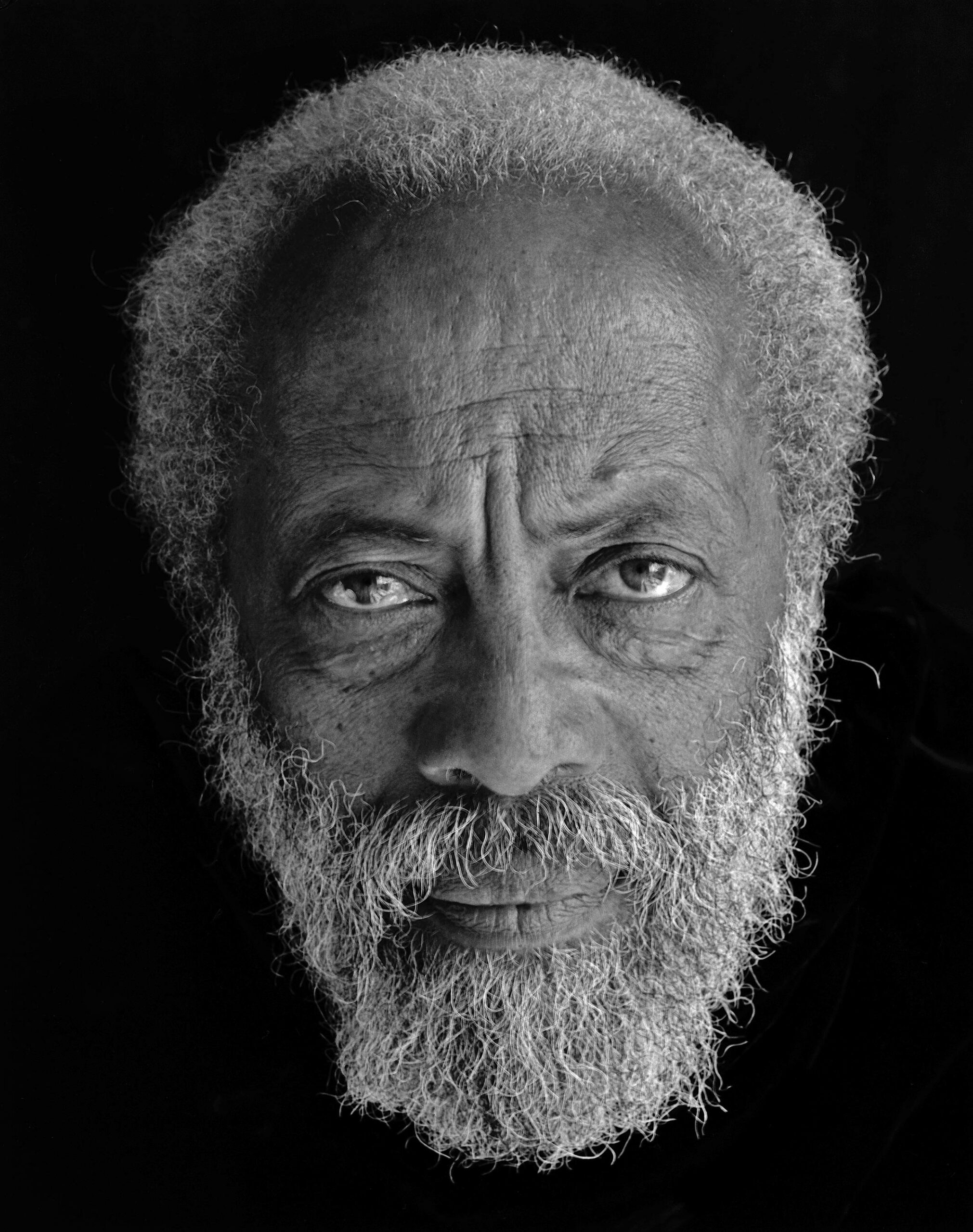

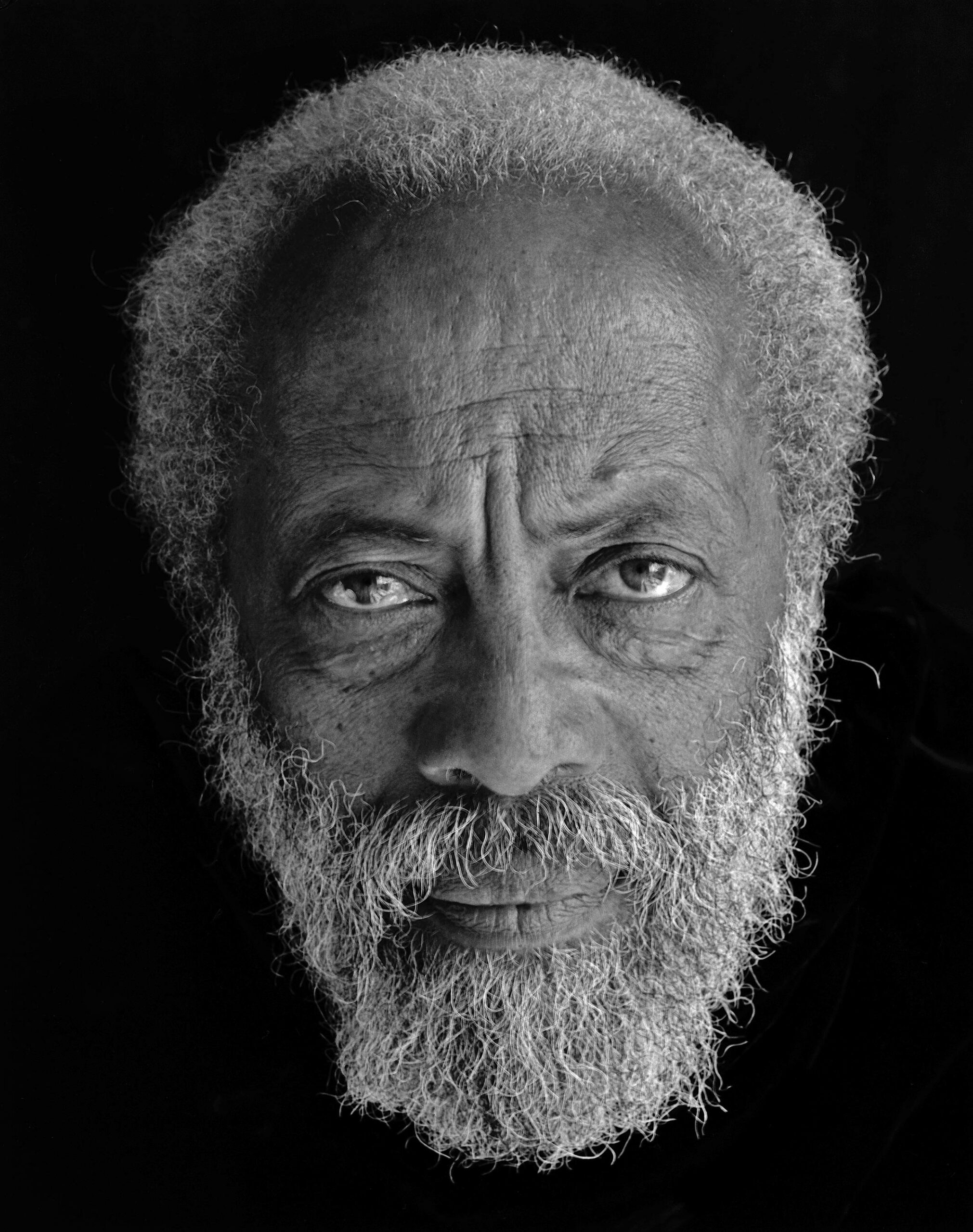

Like her mentors, Dater favors 4×5-in. view cameras for the sharp focus they afford. The format enables the artist to present her subjects, many of whom are women, in abundant detail. Model Twinka Thiebaud, who appears in Dater’s most well-known photograph along with Imogen Cunningham in Yosemite,isgain portrayed in an outdoor setting in a 1970 portrait, Twinka and Tree, San Anselmo, California. Unlike Dater’s playful 1974 composition, in Twinka and Treethe model looks directly into the lens. Thiebaud’s arresting stare can be read as an unqualified demand for the recognition and acknowledgment that women and others continue to fight for. Flash forward more than three decades, the portraits of architect Russ Ellis and author Maxine Hong Kingston likewise capture the individuality of her sitters, but without the contextualizing cues – clothing, jewelry, or setting – that date Dater’s early photographs. Through Ellis and Hong Kingston’s remarkable faces, Dater conveys the confidence comes with age and experience, including her own as a portraitist.

Though thoughtfully organized, the exhibition is light on the photographs in which Dater embedded herself in the New Mexico landscape and regional national parks, beginning in the 1980s. Embracing conceptual and philosophical notions advanced in feminist art practices was a significant departure from Dater’s portrait practice, and the comparatively minimal representation of those photographs undermines a fuller comprehension of how her work has evolved. That minor note critical note aside, Judy Dater: Only Human brings the artist’s work into dialogue with contemporary photographic considerations of identity, gender, and the human condition.