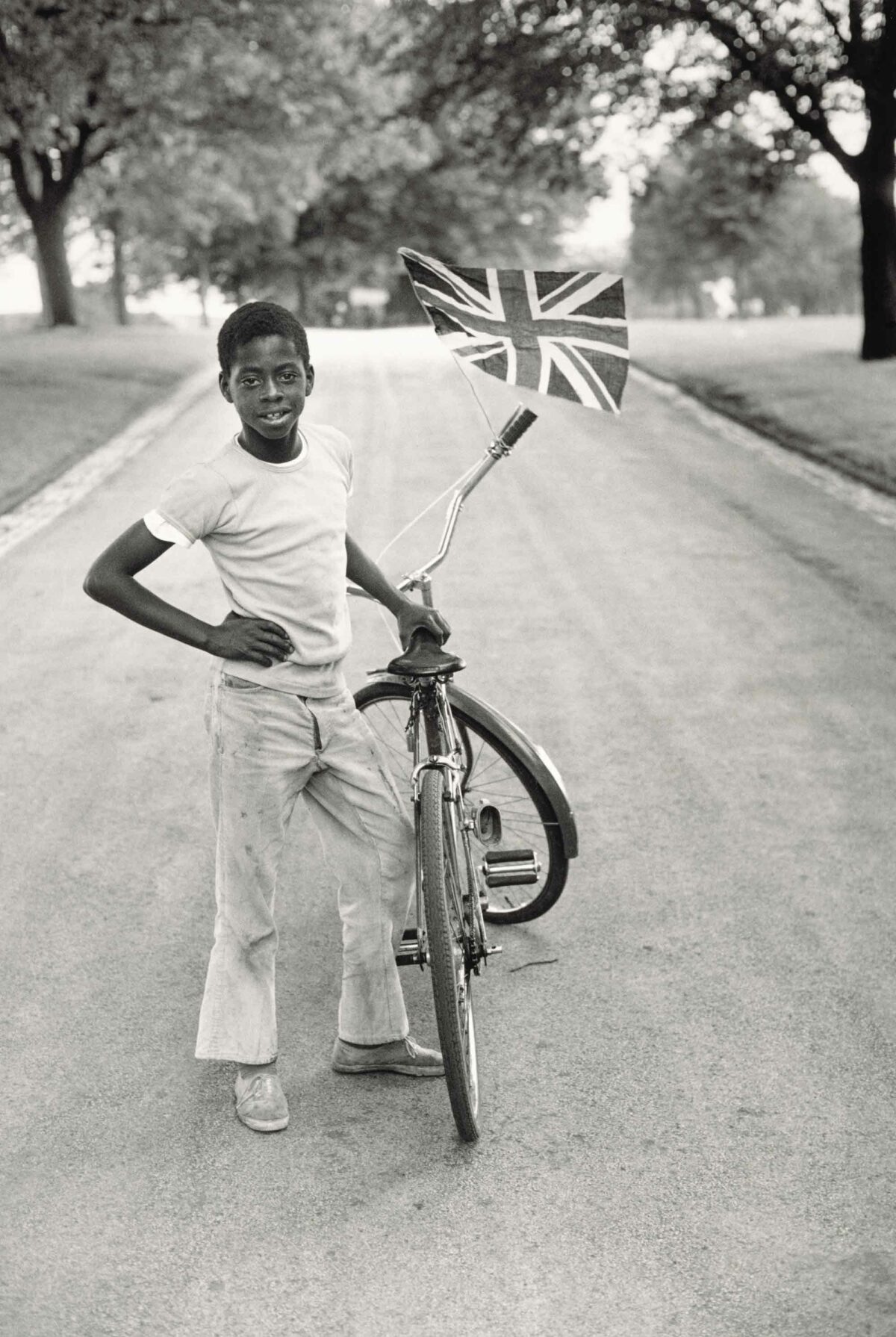

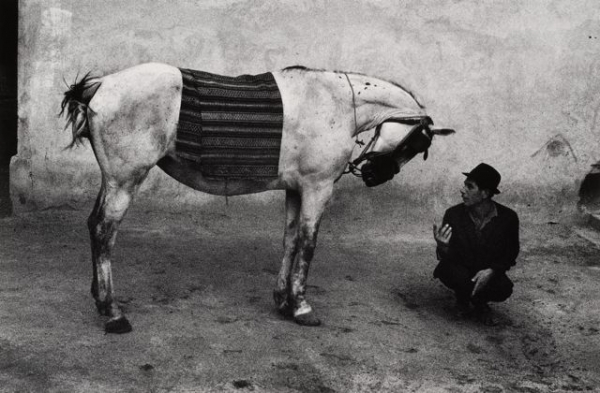

Josef Koudelka’s art and life are comprised of journeys. This is the narrative of Nationality Doubtful, his retrospective on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through September 14 (after which it travels to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid). The title derives from an annotation (“N.D.”) in Koudelka’s passport scribbled by border control, because he had been self-exiled from his native Czechoslovakia and was as nomadic as the Gypsies he famously documented. After chronicling the 1968 week-long Soviet occupation of Prague and its public protests and publishing images of the invasion in magazines in London and New York, Koudelka’s “perilous fame,” writes exhibition curator Matthew Witkovsky in the catalogue, impelled the photographer to wander Europe for years, often sleeping outdoors, photographing other displaced peoples and their divergent notions of home. A worn, hand-annotated map of European festival routes displayed in the gallery seems a tool as important to Koudelka as his Leica.

Artifacts and printed ephemera — the map, but also workbooks and magazine spreads — lend a personalized texture to the many black-and-white prints in this 54-year career survey. The intimate objects are a pleasure to see, but the real evidence of Koudelka’s lifelong, humanist campaign is the photography itself. Koudelka has contributed a wealth of information to the family album of humankind, granting special attention to people whose struggles are inseparable from their existence.

Koudelka did not claim authorship of his famous war photos until 15 years after they were published and circulated, under the protection of Magnum. During those years of exile, Koudelka produced his best work while traveling throughout Europe, including his many panoramic landscapes of empires in transition, from ancient Greece to the Israel-Palestine border. “But where are the people?” famously asked Cartier-Bresson, an admirer of Koudelka’s Gypsies series. The people are present by virtue of their ruins. In fact, Koudelka’s picturesque panoramas mark a shift from his close-ups of faces and funerals to a wider view, from the vantage point of history. The transition in scale, from the specific to the mythic, may be a consequence of maturity, but the pictures are still emotional, even sublime declarations of the persistence of human beings.