The film still is a photographic form extra-steeped in myth. As Cindy Sherman so incisively demonstrated with her “Film Stills,” the single image is a direct portal to all that the film itself represents and to the way cinema seeps into a viewer’s memory bank. In this exhibition of photographs from his early film and video projects, on view through June 11 at Jessica Silverman Gallery, Isaac Julien draws from a deep well of visual, theoretical, and political references. His work has consistently tackled themes of race, sexuality, colonialism, desire, and identity-based gazes – invariably expressed through ravishing, highly composed works.

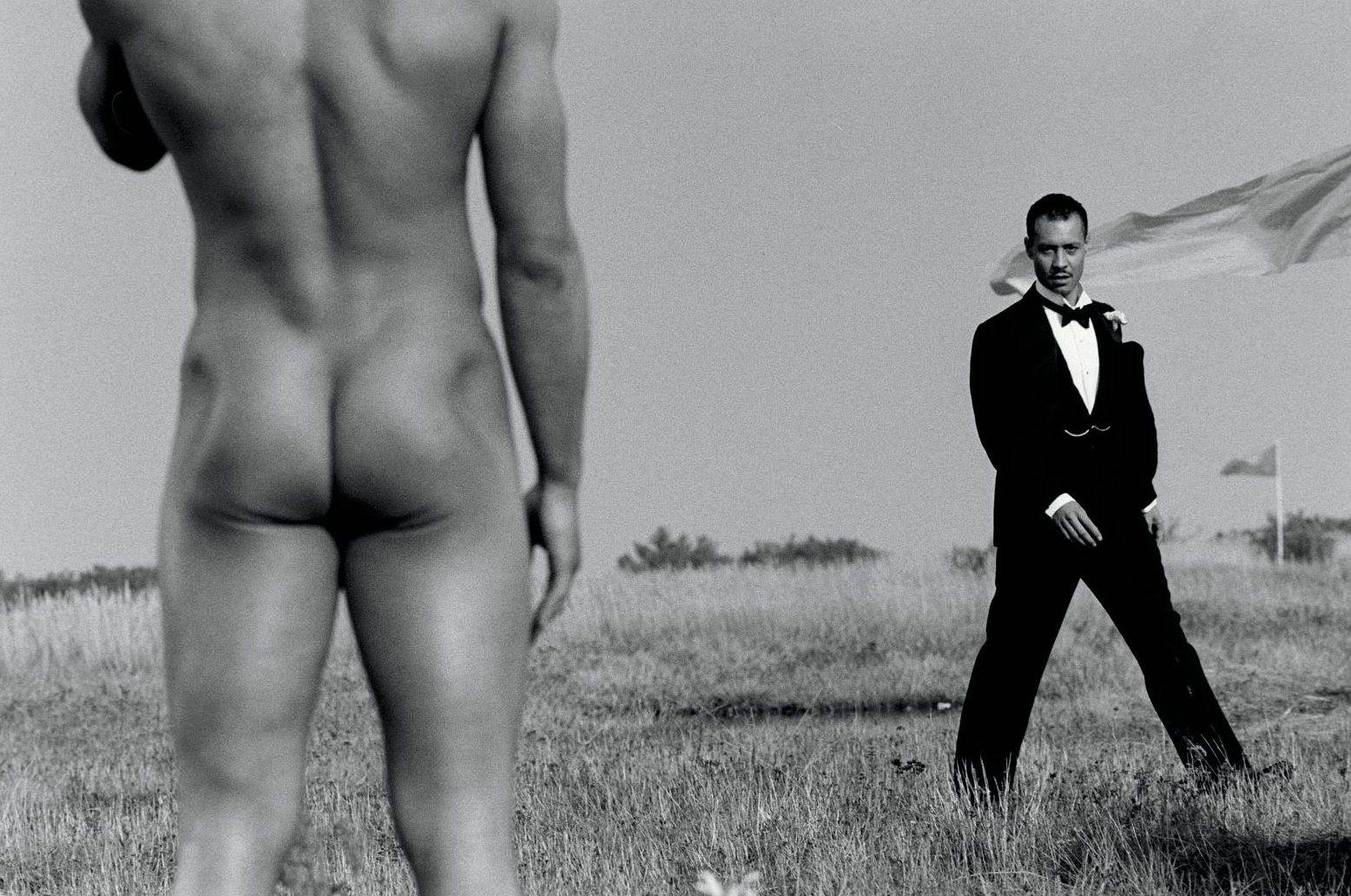

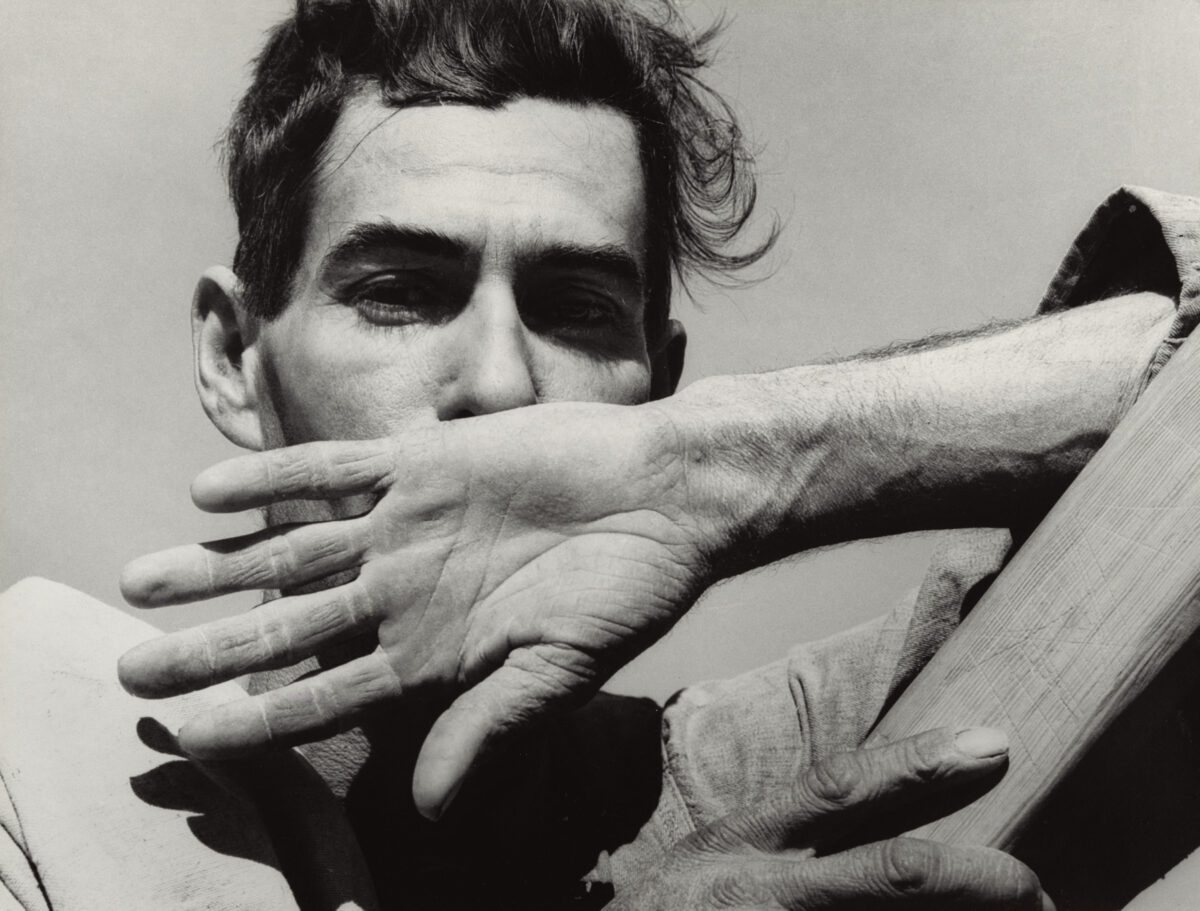

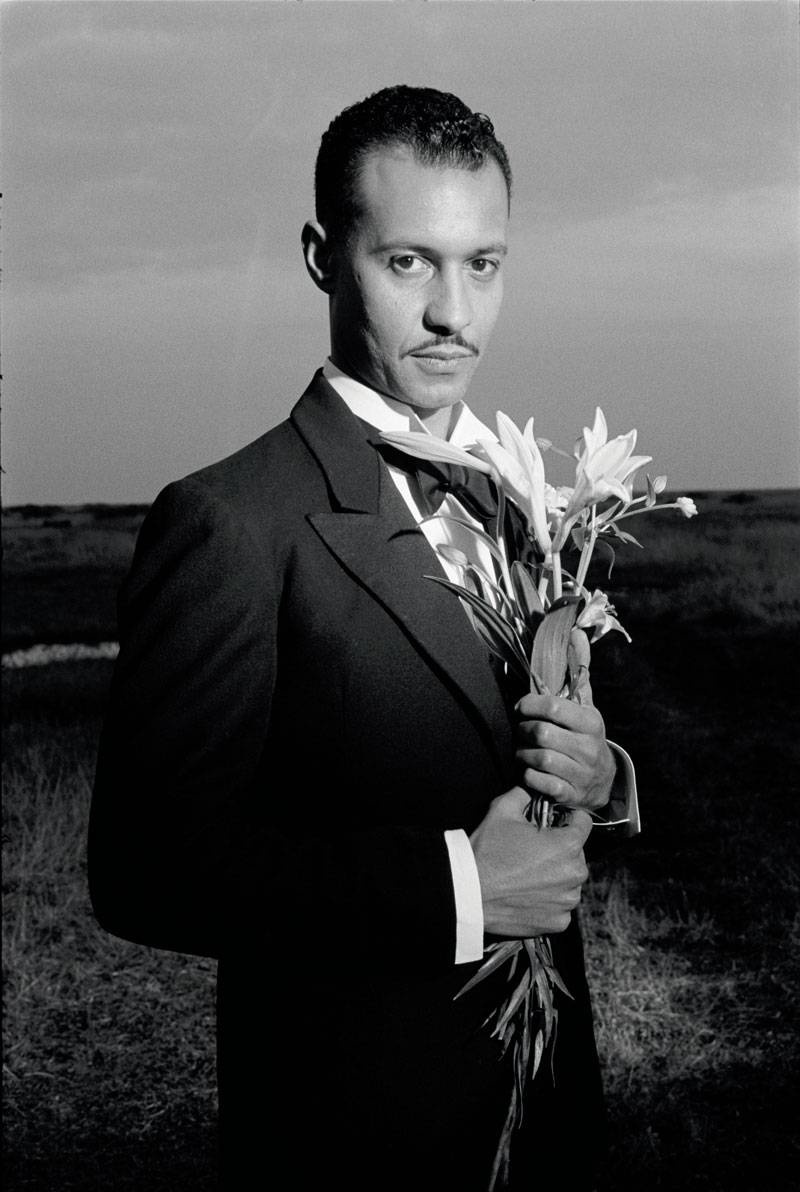

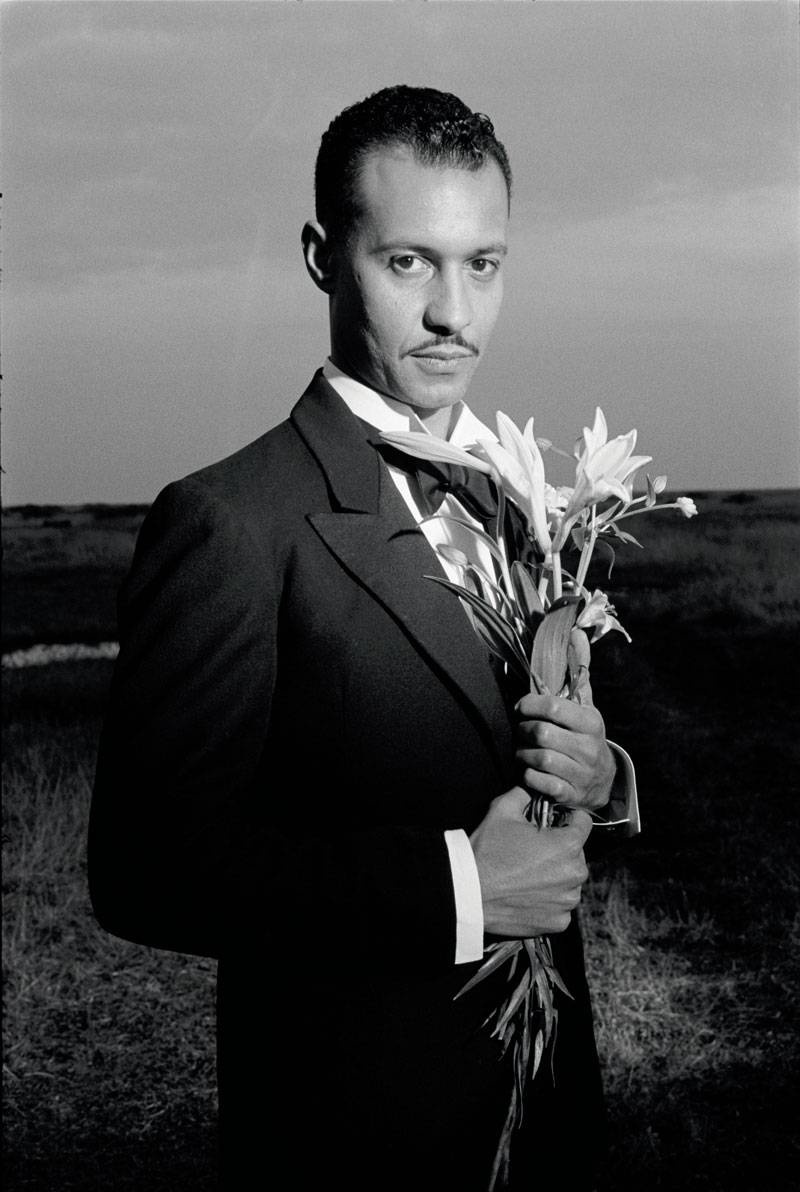

The bulk of the photographs, made with the help of on-set photographers and cinematographers, come from Looking for Langston, the 1989 film that created a dreamlike vision of poet Langston Hughes as a Harlem Renaissance gay icon. The project positioned Julien as an important voice in contemporary art and cinema. The gallery presentation is anchored by larger-than-life – cinematically scaled – black-and-white prints of tuxedoed men in smoky interiors. These are flanked by smaller prints that detail the film’s abundant sensuality and consciously quote photographers such as George Platt Lynes, James Van de Zee, and Robert Mapplethorpe. Although the film’s narrative isn’t quite articulated in the exhibition format, what does come across is the sense of constructed fictions, expressed in production stills, one of which, Mise en Scene No. 1, 1989/2016, brings to mind Larry Sultan’s porn set series, The Valley.

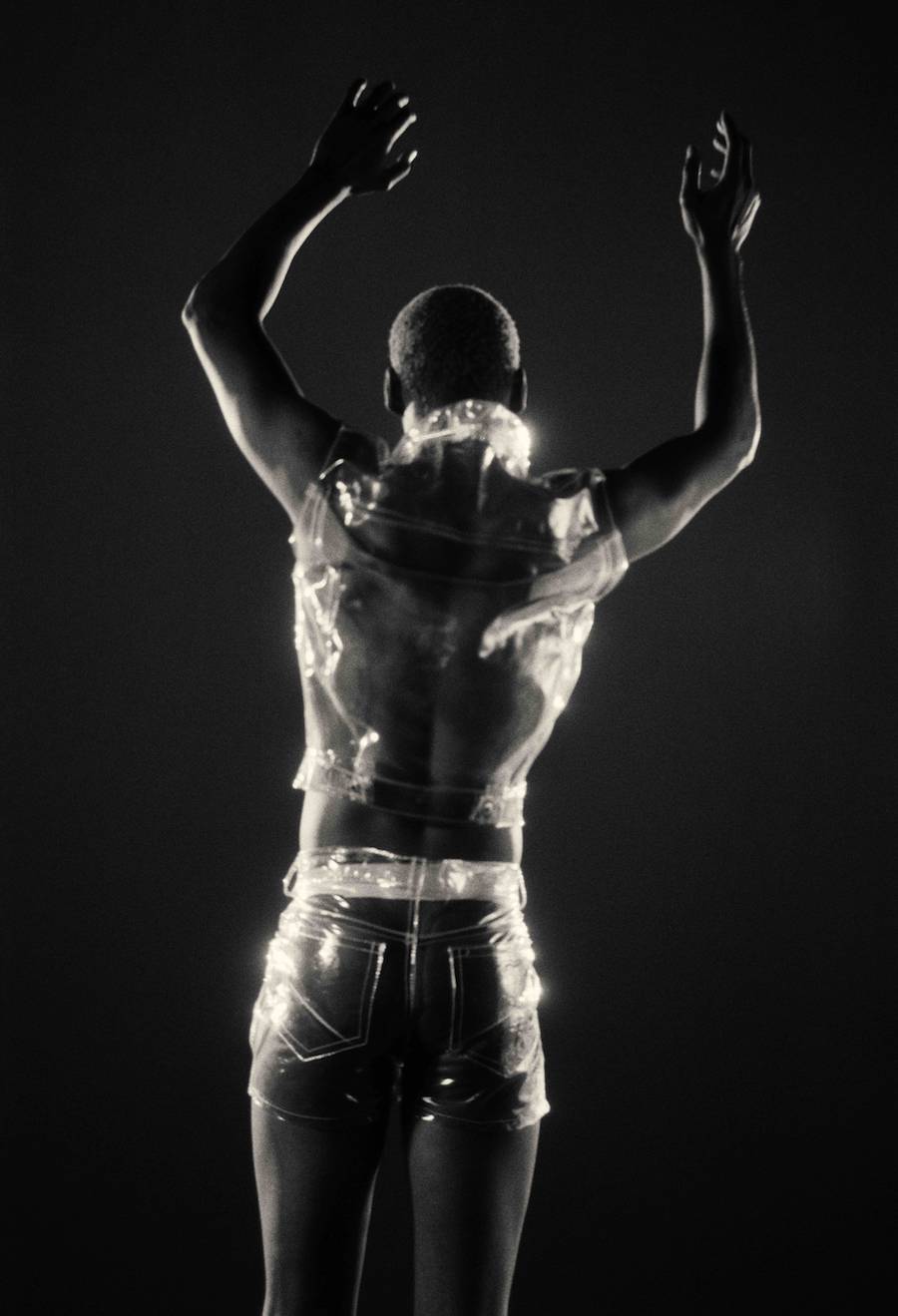

There are fewer images from two other projects – a couple from the kinky Trussed (1996) and eight photogravures from the Western themed The Long Road to Mazátlan (1999-2000) – though these continue to express the various lenses the artist uses to examine queer desire. Over the years, Julien’s work has grown increasingly, almost oppressively elaborate in its ambition and staging—with multi-screen installations and exotic location shoots. This survey of vintage works serves as an elegant reminder of the core of his practice and the potency of his vision.