There is a famous story about Irving Penn that epitomizes the formal perfection of his work: After being presented with 500 lemons from which to select the singular best of the bunch, he proceeded to take 500 photographs of that one lemon to arrive at l’image juste. Such uncompromising rigor is manifest throughout the more than 200 precision-crafted photographs in Irving Penn: Centennial, the comprehensive, elegant, and utterly pleasurable retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 30.

Penn started out as a painter. His visual preoccupation with balance, volume, shape, and line is what defines the classical signature of a Penn photograph, whether in the genre of fashion, portraiture, or still life – all of which are well represented in the show. He transformed the fashion photograph, for example, into a study of sculptural mass, as if the dress-on-a-model were akin to a sleek Brancusi obelisk, or a balloon sleeve resting on a surface had the weight of an abstract form by Henry Moore.

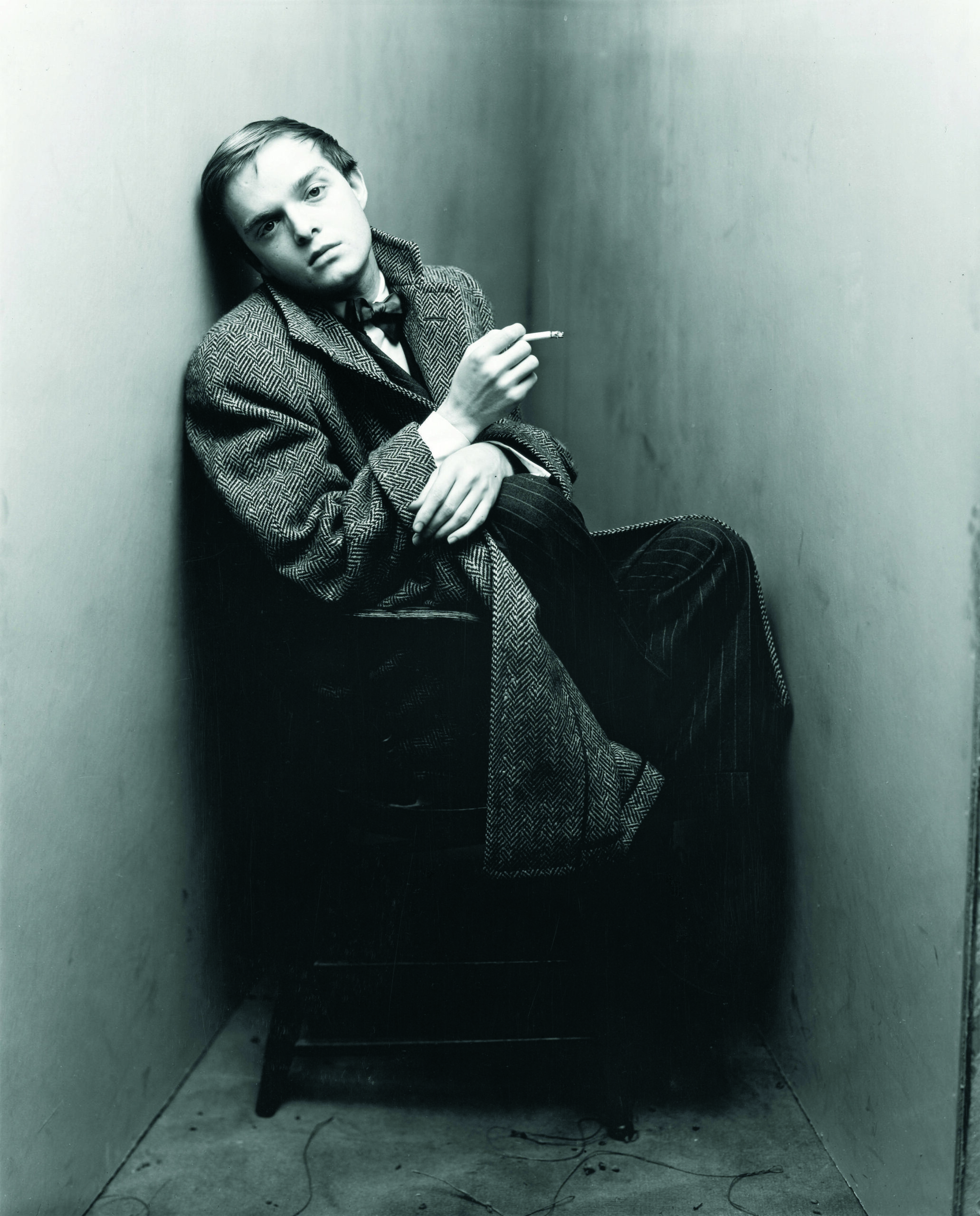

During his lifetime, Penn made portraits of so many prominent cultural figures of the 20th century that he came to be regarded as an equal among them. The show includes a pantheon of these accomplished individuals, as well as ethnographic portraits of tribesmen in New Guinea and Peru. He rendered all of his sitters in nothing less than monumental terms, with bold, contrasting light and rich, mottled tones, as if to chisel each one for the ages in stone. Early in his career, when he felt unequal to his subjects’ fame or success, he devised a narrow corner as a backdrop for sitters in his studio. Not a few of his subjects felt uncomfortably backed into that punishing corner: Truman Capote, for example, hardly the shrinking violet, wrapped himself in his coat and stood on a chair – cloaked, beseeching, trapped.

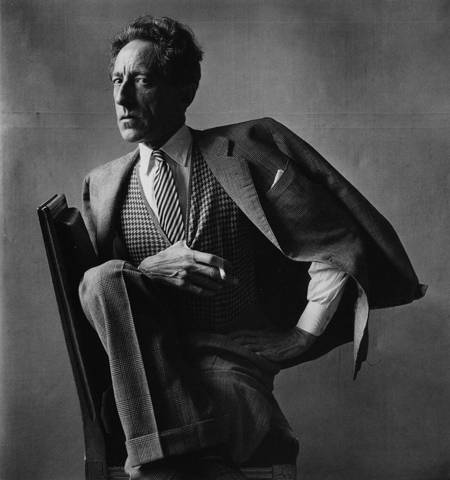

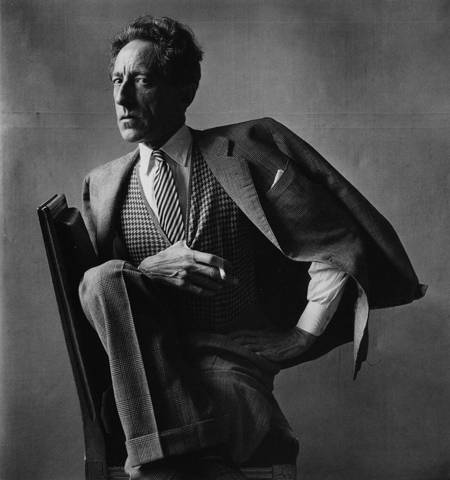

Vogue sent Penn to Paris in 1948, where he photographed le Tout-Paris. In his portrait of Jean Cocteau, the intricately checked patterns in his subject’s suit and tie pop out in vivid, tactile detail. Cocteau’s coat is draped over his extended elbow with an air of studied flamboyance; but, then, his expression registers the fierce intelligence of a keen observer, as if he is taking our measure while deigning to allow us to take his.

Penn’s photographs have such physical presence and formal resolve that it’s easy to forget they were made to fulfill the editorial needs of a magazine. How rare it is, then, that the editorial requirements of any magazine should correspond so inextricably to the aesthetic sensibility of an artist. In Penn’s case, his will took charge over fate in what might have been just a lucky match: while his editorial assignments were destined for the page, he approached each one as a blank canvas on which to construct a composition that drew on the formal building blocks of modernism to explore the visual language of photography. In so doing, he elevated an entire profession and took the medium forward.