Jay DeFeo was a pivotal figure in the Bay Area art scene from the mid-fifties until her death in 1989. She is most closely identified with her legendary work, The Rose (1958-66), a hybrid of painting and sculpture consisting of roughly a ton of paint, which fellow artist George Herms called “the ultimate living being.” The work has since secured her place as one of the most important artists to emerge from the West Coast counterculture of the midcentury. Upon completion of The Rose, DeFeo left the artistic ferment of the San Francisco Beat scene and relocated to the small town of Larkspur in Marin County. After a four-year hiatus from her work – a restorative period after the intense labors of The Rose, as well as the collapse of her marriage to artist Wally Hedrick – DeFeo returned to artmaking, a move facilitated almost completely by her engagement with photography.

If The Rose was a fundamental reconsideration of what a painting could be, her photographic work is equally boundary pushing. Curator Corey Keller writes in the monograph published to coincide with the show (Jay DeFeo: Photographic Work, Delmonico Books/ The Jay DeFeo Foundation) that DeFeo “deployed photography’s every capacity – its ability to represent and to duplicate, to document, commemorate, and historicize – and fully explored its chemical and material properties.” This expansive approach was amply demonstrated in the revelatory show Inventing Objects: Jay DeFeo’s Photographic Work, which collected more than 80 prints, mostly produced between 1971 and 1976, few of which were ever shown in her lifetime.

“More so than most artists, I maintain a kind of consciousness of everything I’ve ever done while I’m engaged on a current work,” DeFeo wrote in 1978. In her photographs as in her paintings and other work, a private language of elemental forms appear and reappear like relics – subject to repetition and variation until they are transformed into almost ritual objects: a head of cauliflower; a battered pair of old shoes; her dentures. In an untitled work from 1972, the earpiece of an antique candlestick telephone, another recurring motif, has been replaced with a flame-shaped light bulb, creating a lamp of sorts. She called it her “electric telephone.” It’s the sort of visual pun beloved by the Surrealists, but it also refers obliquely to an important part of her daily life at the time: her ongoing, inspirational phone conversations with fellow Bay Area artist Bruce Conner.

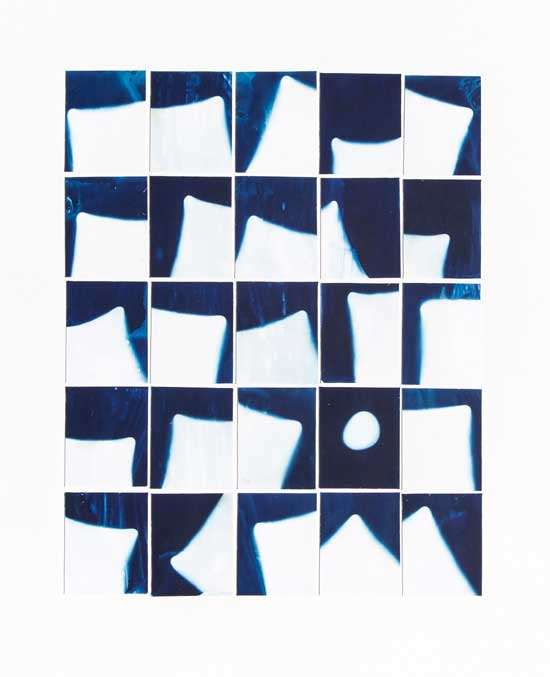

DeFeo’s focus on the elements of chance, play, and the marvelous already aligned her closely with Surrealist attitudes. Seeing Man Ray’s 1974 show at the San Francisco Museum of Art gave her renewed confidence in the approaches she’d been employing. In Salvador Dali’s Birthday Party, a suite of “chemigrams” from 1973, she exposed photographic paper to light and then poured developer and fixer over it, producing painterly, Rorschach-like washes of tonal contrast. It is photography reduced to its elemental basics – light and chemistry – and subjected to a purely chance procedure.

As art historian Rosalind Krauss argued, photography lies at the heart of the Surrealist enterprise. It can both reveal hidden, unconscious realities and demonstrate the transformative power of vision, revealing what DeFeo called “enigmatic figurative references.” The power of her photography lies in the ways it renders the quotidian fantastic. Her uncanny manipulations of the real reveal a complexity that transcends the literal, while never quite shaking off a classical ideal of beauty.