In January, the seductive, sometimes disturbing fashion photography wunderkind Juergen Teller published portraits of Rihanna in Paris Vogue. It took U.S. critics six months to realize the problem: they looked just like the work of artist Mickalene Thomas. Teller had riffed on her languorous poses, her palette, and patterns. The gallery that represents both artists, Lehmann Maupin, issued a statement saying it only deals with Teller’s “fine art practice, which is different than his commercial and editorial work”— as if there is a clear, traceable line between an artist’s “fine art” work and work for hire.

Guy Bourdin riffed on his peer, painter Francis Bacon, for his 1954 fashion photo Chapeau Cho, now on view in the Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography, 1911-2011exhibition at the Getty Museum through October 21. That same year, Bacon had painted Figure with Meat, the pope flanked by two animal carcasses. Bourdin placed his model, wearing a sleek, flower-adorned black hat, in the left-hand corner and hung six gutted rabbits from a butcher’s rack behind her. The result placed elegance and gnarliness on the same pedestal. This image, and the show, upends the assumption that art and commercial image-making are separate. In fact, they depend upon each other. The art world’s aversion to this notion reflects a weird need, despite art’s own inflated market, to believe that artists remain unsullied by market pressures.

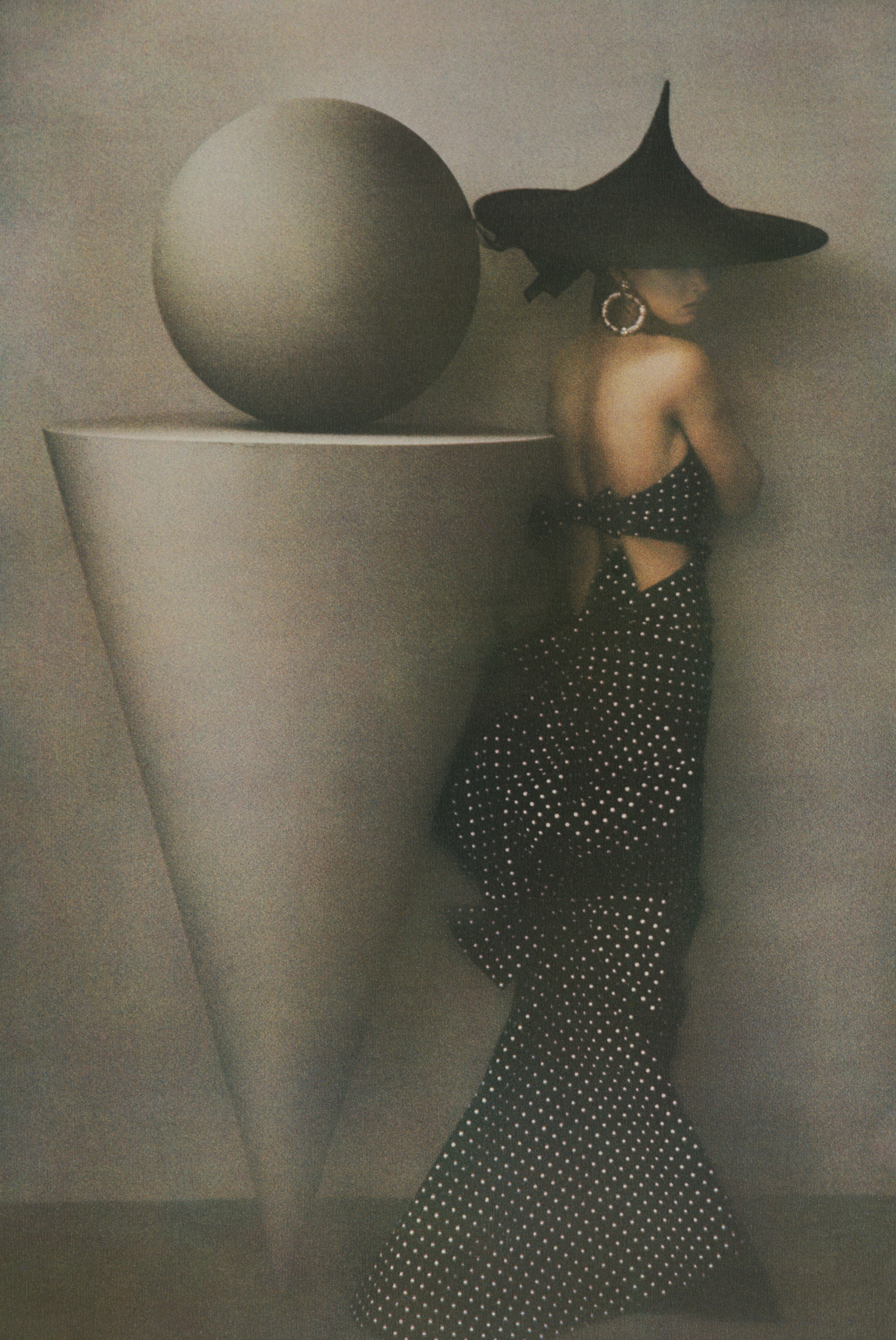

Curated by the Getty’s Paul Martineau and drawn largely from the museum’s collection, the show has the Getty’s characteristic dryness – photos matted uniformly, hung too close together. Designer dresses on white pedestals give the show a sculptural element. Yet despite their beauty, the clothes speak a different language than the images, which manipulate and compose the fantasy of beauty. Work by Man Ray and Edward Steichen open the exhibition, which proceeds mostly chronologically. According to a wall label, both “needed the work” and neither cared for fashion, though they certainly understood glamour’s visual vocabulary. Man Ray’s 1928 image of Nancy Cunard, arms drowning in wooden bracelets, is a pattern symphony. Steichen’s Lee Miller: The Evening Mode is Fully Aware of the Back(1928) shows the model and exceptional photographer Miller in a tulle dress with scooped back, every curve matched with an angle.

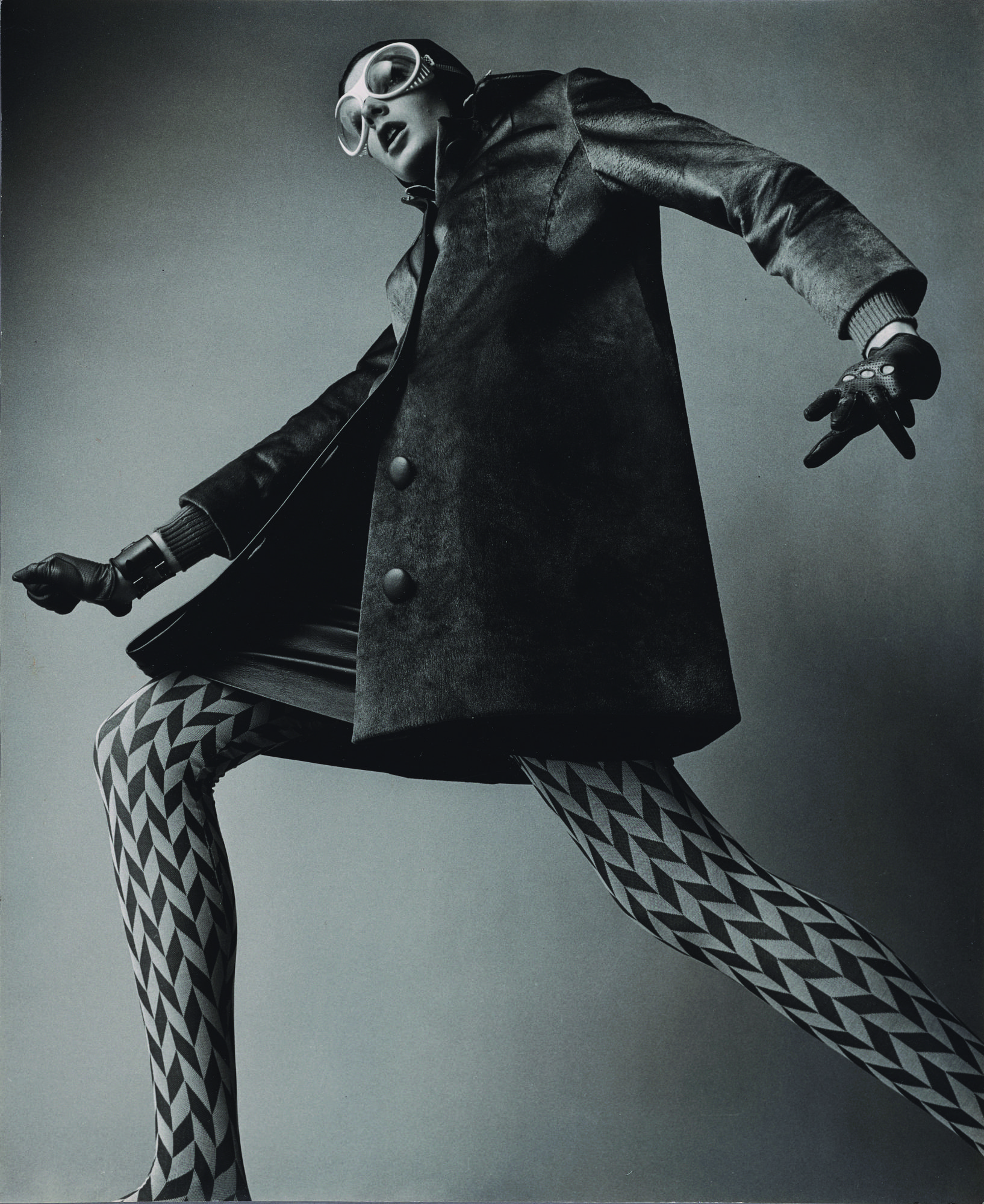

Horst P. Horst, who made his name in the commercial world, turned his 1938 shoot with model Helen Bennett into an almost postmodern performance of repetition: she sits on a chair in a silky gown while three nearly life-sized framed photos of her in similar silky gowns hang behind her. Toni Frissell, among the minority of female photographers in the show, photographed a subject laying on a dock in a newly invented bikini, her body slim but real in its curves and fleshiness. The show, like both the fashion and art world, leaves some diversity to be desired. A 1965 Richard Avedon photograph of China Machado is one of the earliest of a woman of color.

There is, however, ample diversity of style: from the tight construction of Irving Penn to the spontaneity of Jamel Shabazz’s colorful 1980s street style shots and the wispy rawness of the late Corinne Day’s 1990s work. Day’s photograph Rose in Gold Trousers (1993), shot for a FACE magazine fashion spread, depicts a topless model in lamé pants laying on brown carpet, holding her head up to see a dated TV set. The listless, laissez-faire image would have perhaps been less relevant had it appeared exclusively on a gallery wall, where it was shown only after Day’s art-for-hire captured a zeitgeist.