For Valdir Cruz, Guarapuava will always be home. It is the place where he learned to hunt with a slingshot and fish with his hands. It is where he recognizes the songs of the birds and knows the names of the rivers and trees. It is where he sold oranges on the streets and snuck into movies and fell in love for the first time.

Even after Cruz left the Brazilian countryside, at the age of 23, for the United States, Guarapuava remained a photographic base of sorts, a place where he could return again and again with his camera to flex his photographic muscle. Over the last 30 years, he’s brought with him the knowing eye of a native son along with the political and social scrutiny of an anthropologist.

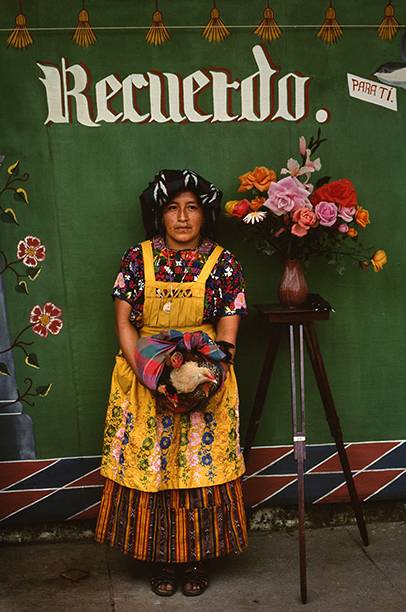

His exhibition at Throckmorton Fine Art through November 1 feels at once intimate and sweeping, personal yet documentary in style. As Cruz’s lens traverses the rural landscape of his past, faces seem to peer out of a family album — albeit a diverse one, made up of indigenous peoples, cattle drivers, potato pickers, Gypsies, and African and German immigrants. They are by turns joyful, somber, and proud. In one, the gaze of an anonymous Gypsy woman pierces the camera, her expression a mystery.

Amongst these portraits, in a sign of the peoples’ strong connection to their environment, hang photos of Guarapuava’s natural beauty. A lone white horse grazes along the still Jordāo River; water, made silky and smooth through long exposure, glides over dark cliffs; a small wooden chapel at the back of a farm peeks through the morning fog.

Cruz’s black-and-white photos speak not just of life, but of destruction. The body of water, for instance, in Cruz’s photo, Landscape with Trees and Lake, is artificial, created by an electrical dam. The view, Cruz said in an interview, “used to be beautiful.” A portrait of an indigenous Guarani man, meanwhile, contains the history of a people whose population has been decimated through the years by colonialism and slavery. The traditional cattle driving Cruz depicts, likewise, is increasingly rare, replaced mostly by trucking.

“Photography is a vision; the rest is technique,” Cruz’s recounts his friend George Stone telling him in the afterward to his book, Guarapuava. Indeed, while Cruz’s technique has improved over the course of 30 years as he evolved from a novice to a master, his vision is consistent, telling a story of timeless grace amid change and ruination.