As I sat reading Abelardo Morell’s catalogue, a spot of sunlight hit the glossy page and turned the black font to gleaming, unreadable gold. It was the type of enchanting light effect Morell might also enjoy. The photographer has spent the past 25 years coaxing curious visual phenomena from straightforward materials like paper, books, rooms, light, and land, often combining them into perceptually expansive experiences.

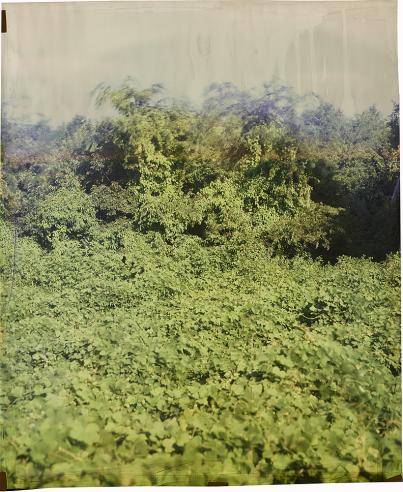

Morell’s magical realism is convincing because the photographer is a techie obsessed with getting his magic just right. He has perfected an unusual technique of landscape photography that makes use of a mobile camera obscura (via customized tent), rigged with a periscope-like lens, to compress a distant vista and its immediate ground into a single image. For instance, gravel and weeds are transposed atop a Texas mountainscape, with a dense, sunny blue impasto of pebbles for sky. Morell likens the painterly effect to Monet, but Steichen is also apt. These “tent camera photographs,” which Morell has been producing in the field since 2007, effectively emit a sense of place, merging the experience of seeing a place and standing there.

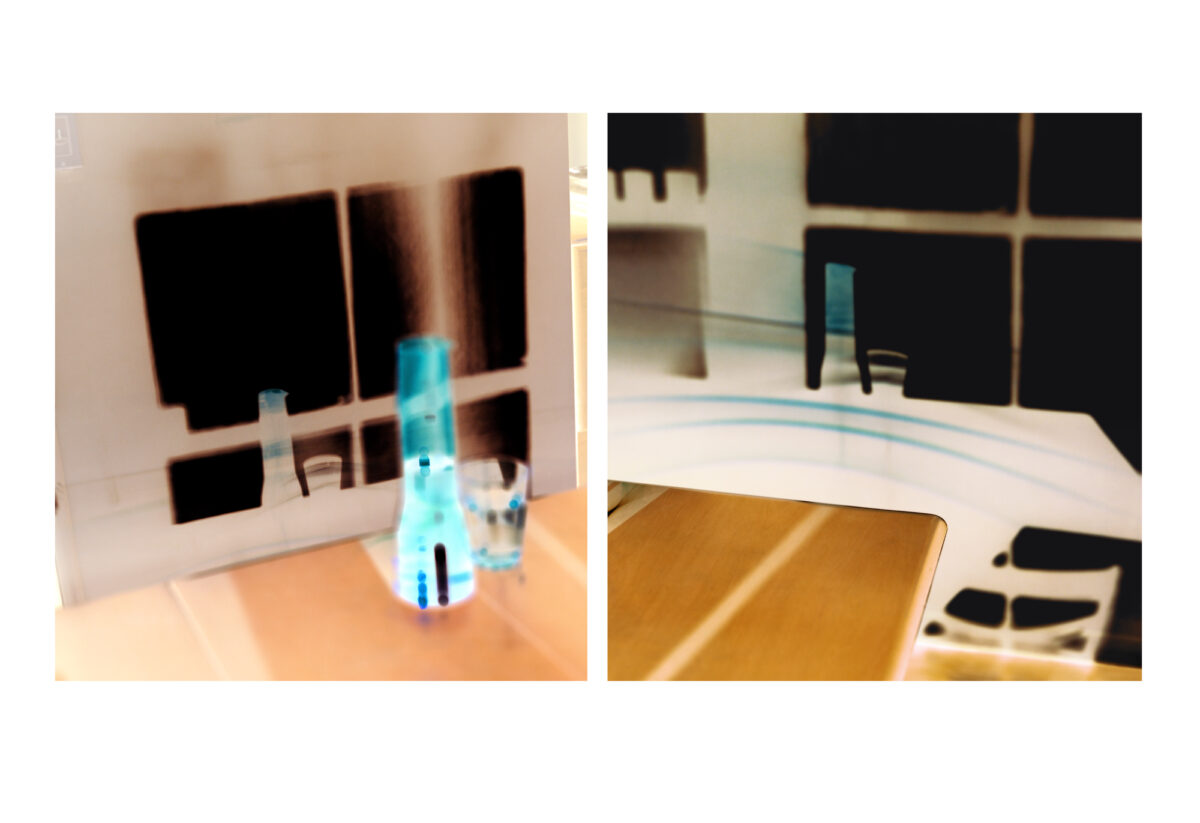

Amid Morell’s nationally touring retrospective exhibition, on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through September 2, Stephen Daiter Gallery is showing a selection of his camera obscura images (through August 3, 2013). Morell’s first experiments with this proto-photographic technique in the early 1990s produced black-and-white images from long-exposures (using film). Now, with his tent apparatus, a digital back, and a prism, Morell shoots in color, and quickly, preserving what he calls the scene’s “momentary light.”

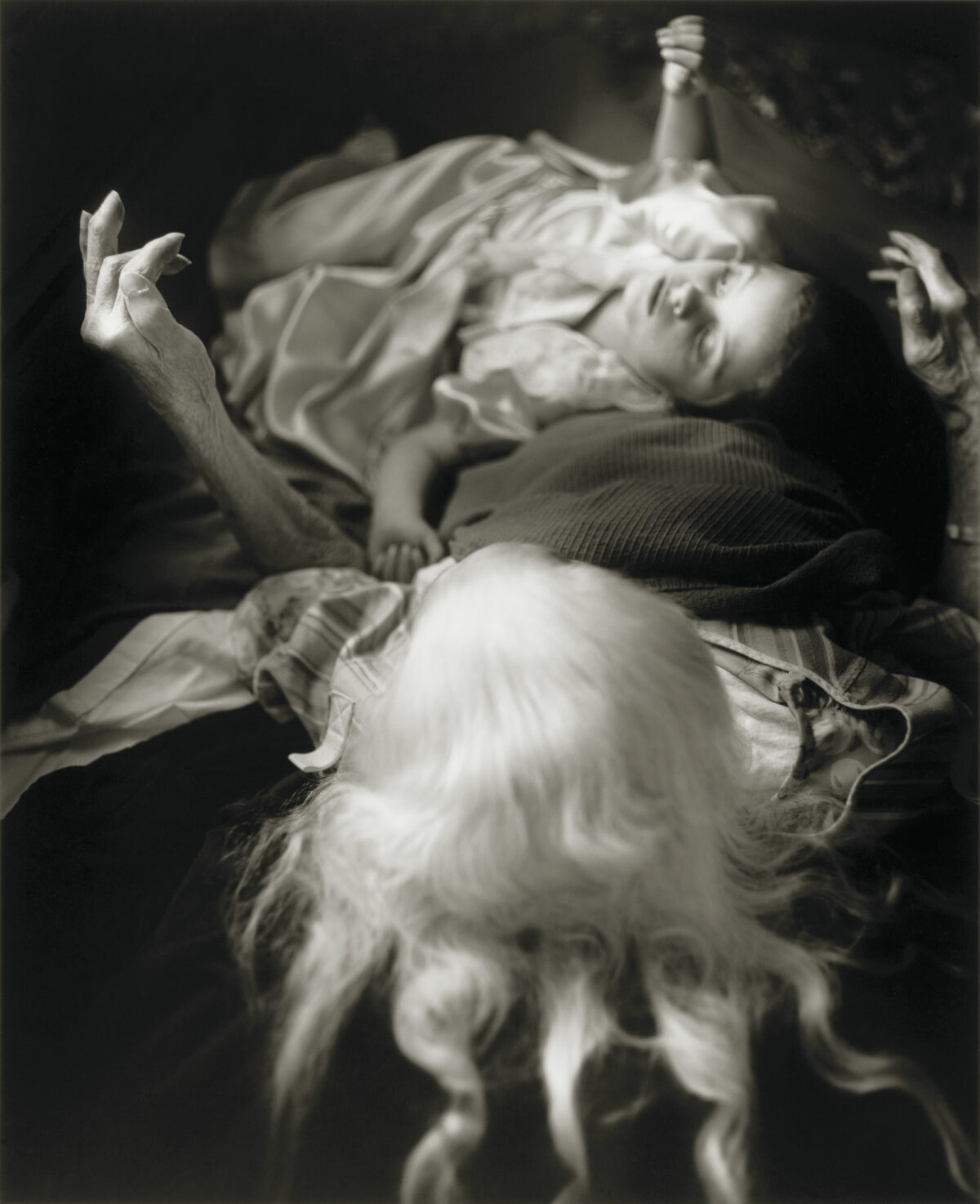

He updates his classic, moody Sea in the Attic, from 1994, with a 2009 image of a nearly identical scene and subject. In spite of its familiarity, the camera obscura continues to fascinate photographers and viewers alike, and, as Morell shows, it is an adaptable technology. But, to what end? Morell is a staunch formalist, even as the blood of former battles, from Manifest Destiny to ecological disasters, begs to be dredged from the land of the American West, where Morell often sets up a tent. He succeeds at creating rich, myth-like landscapes, while ignoring the history of those landscapes. For a technology revivalist, Morell is surprisingly thin on history in his recent camera obscura images, instead favoring the tourist’s wonder-seeking, but superficial, view.