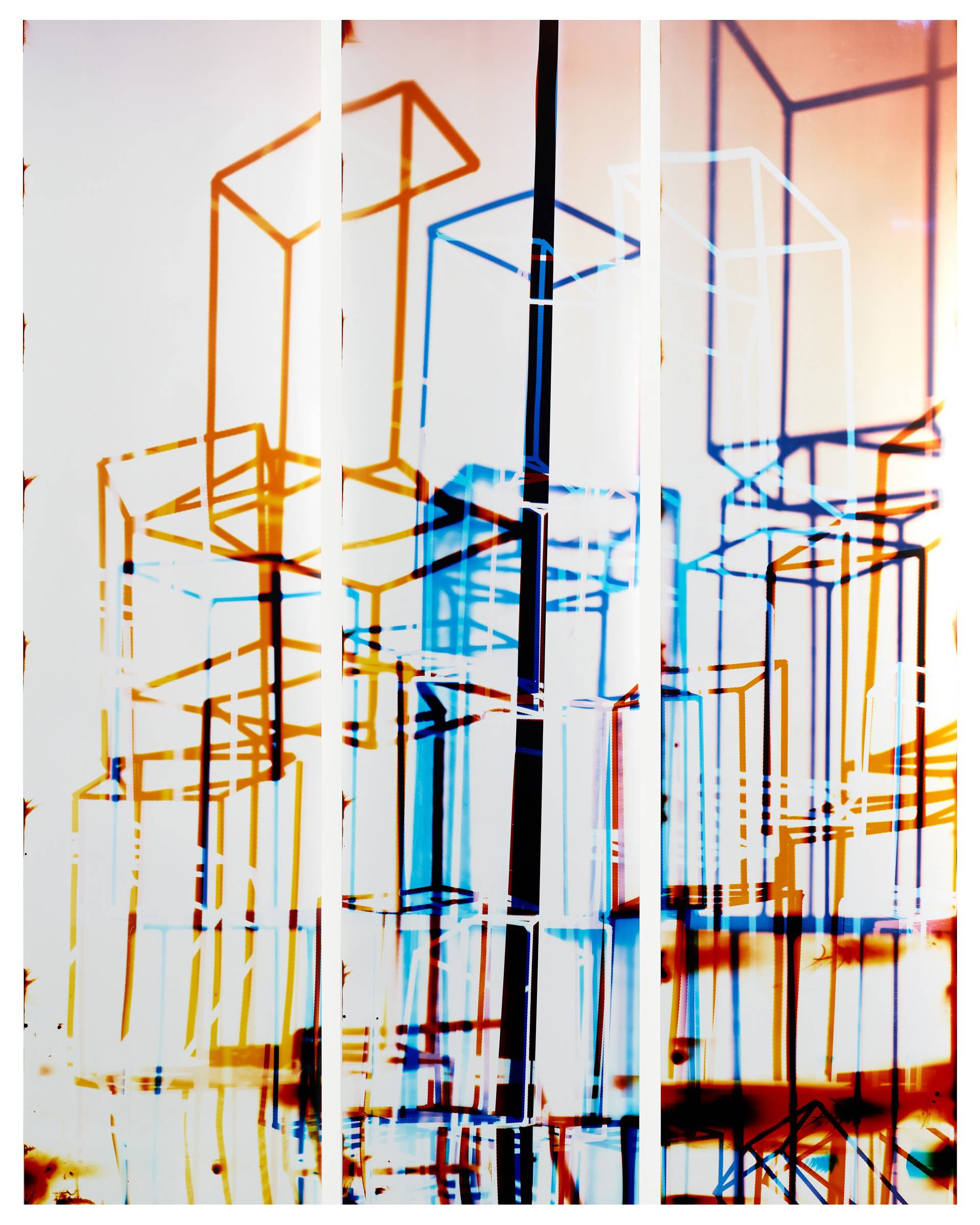

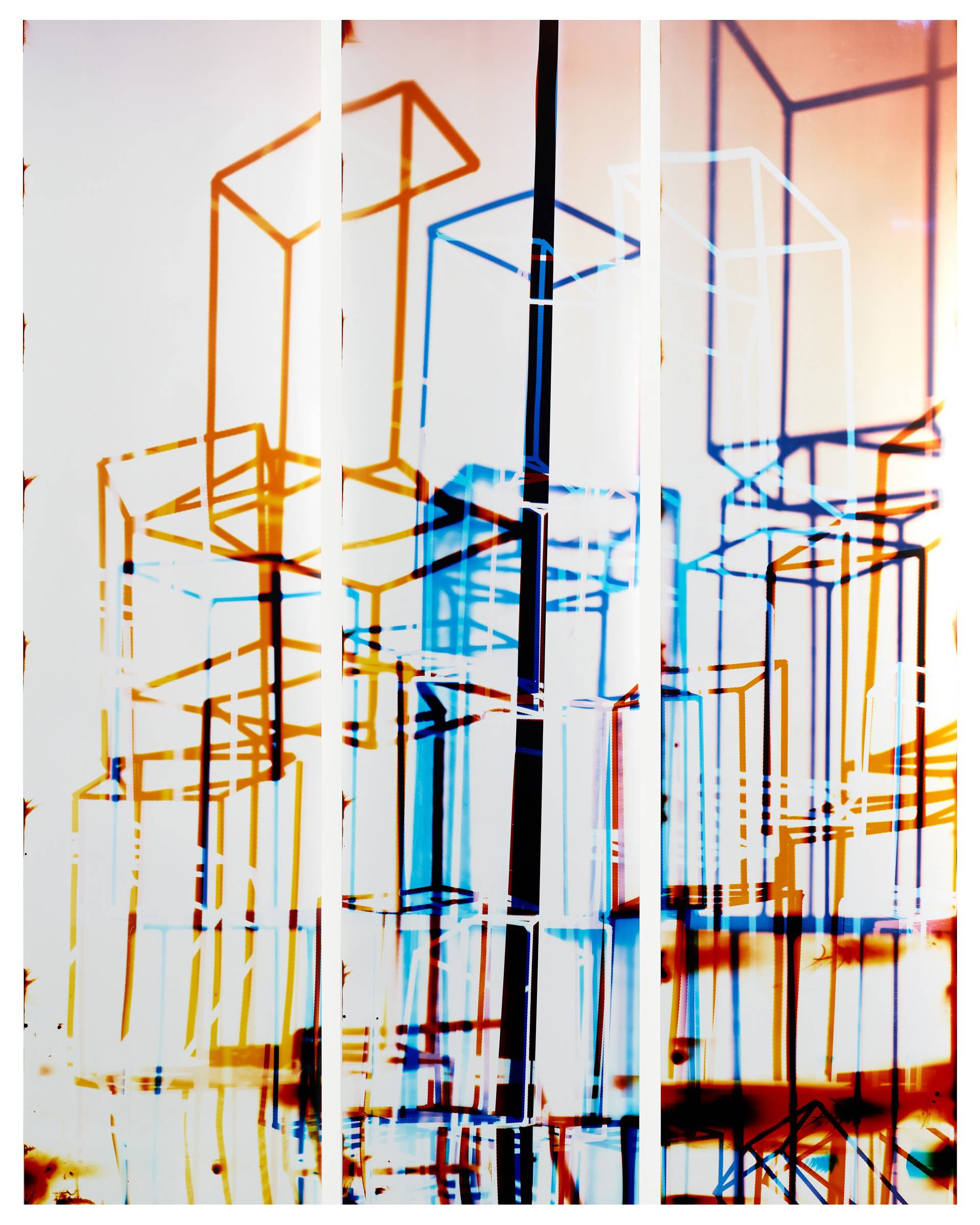

In the classic optical illusion known as the Necker cube, spatial orientation is unstable. The outlined cube can be read in two different ways, as if seen from slightly above or slightly below – or as oscillating between those mutually exclusive positions. Farrah Karapetian’s photograms have often evoked a similar ambiguity through the interplay of opaque and translucent forms, shadow and void. In her show at Von Lintel Gallery through December 23, Karapetian stages the Necker cube phenomenon itself, writ large.

She built three dozen skeletal rectangular blocks out of rebar to use as a “sculptural negative,” and repeatedly stacked and reconfigured them, exposing the arrangements to color-filtered light while on or in front of chromogenic paper. Her performative assembly and disassembly of the negative produced dynamically unsettled images. Sometimes the linear patterns glow clear and neat as neon tubing, and sometimes the lines stutter into dense lattices, cacophonous, intermittent scaffolding. The rebar’s ribbed surface gives the lines they generate on the page a little tooth, a bit of vibration.

The light within these images is radiant, viscous. Passages of lush amber, cyan, gold, and musky red flicker and soak, punctuated by brilliant white absences. A handful of the rebar blocks have a solid wall of smooth or wrinkled blue resin, widening the textural range of light cast upon the paper. Karapetian installed the rebar and resin modules in a thoughtful tumble in the gallery, among the photograms they generated. However self-evident the physical blocks on the ground, their corresponding traces on paper are gloriously elusive. Every image, no matter the size (one is eight feet high), is an interrupted fragment, subject to a multiplicity of readings – optical, metaphorical, even political.

Two photograms that don’t employ the rebar-block template inflect the meaning of the rest. “Distressed” presents the American flag hanging upside down, its stripes sagging and seeming to leach blood. The other piece, less visceral, but signaling urgent danger as well, is sharp and direct as a protest poster: “Build This Wall” it commands, pointing to a barrier between a church and the Capitol building, effectively church and state. Building Dwelling Thinking thus becomes a show that, beyond its vigorous beauty, provokes thought about a variety of truths and illusions.