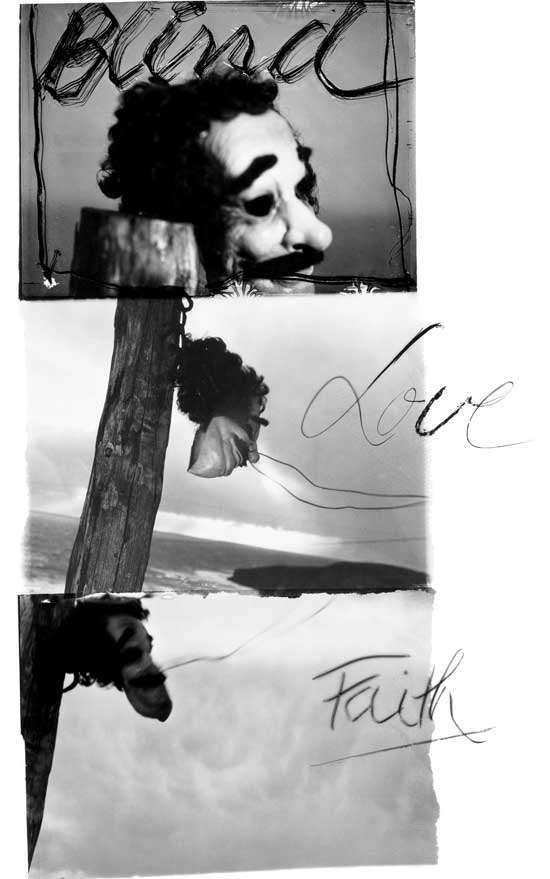

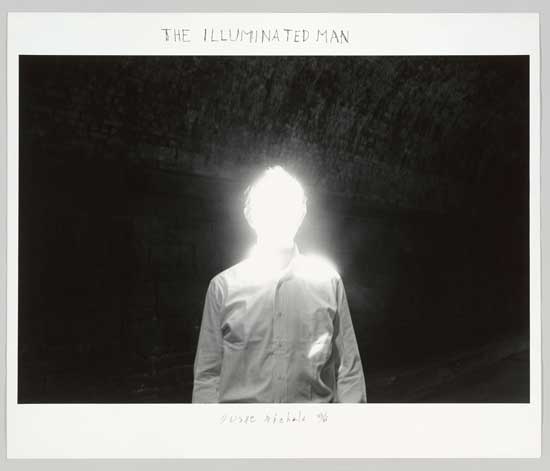

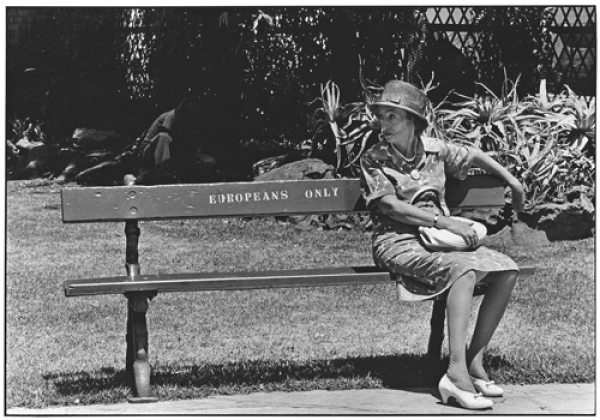

In 2011, the South African National Gallery in Capetown was devoted to the work of two photographers and both responded in very different ways to the realities of what was once a divided country: Roger Ballen and Ernest Cole (1940-1990). Ballen was already internationally recognized in art circles for an expressionistic, theatrical style that explored the idea of marginality in South African society. Cole (who died just after the release of Nelson Mandela) was almost unknown. No significant exhibition of his work had ever been presented in the United States – or in South Africa, for that matter. The exhibition in South Africa was mounted by Sweden’s Hasselbald Foundation, which houses the Cole archive, and that is substantially the show at the Grey Art Gallery through December 6. Having been conditioned by many books and exhibitions of anti-apartheid photojournalism, viewers might miss the enormous significance of these pictures. If some of these black-and-white photos of life under pass laws and segregated facilities seem familiar, it is because Cole set the standard for showing life behind racial barriers.

Born in a township near Pretoria, Cole worked for black publications, but all the while he nursed a project he hoped would reveal the true character of apartheid, in pictures that could never be published in South Africa. In 1966 he was arrested in connection with a street gang he was photographing. Under pressure to give information, he somehow managed to obtain a passport and leave the country. He never returned. He spent parts of the next 25 years in Sweden, London, and New York, where his life spiraled downward. He became homeless, possibly the result of bipolar disorder, and he died of pancreatic cancer.

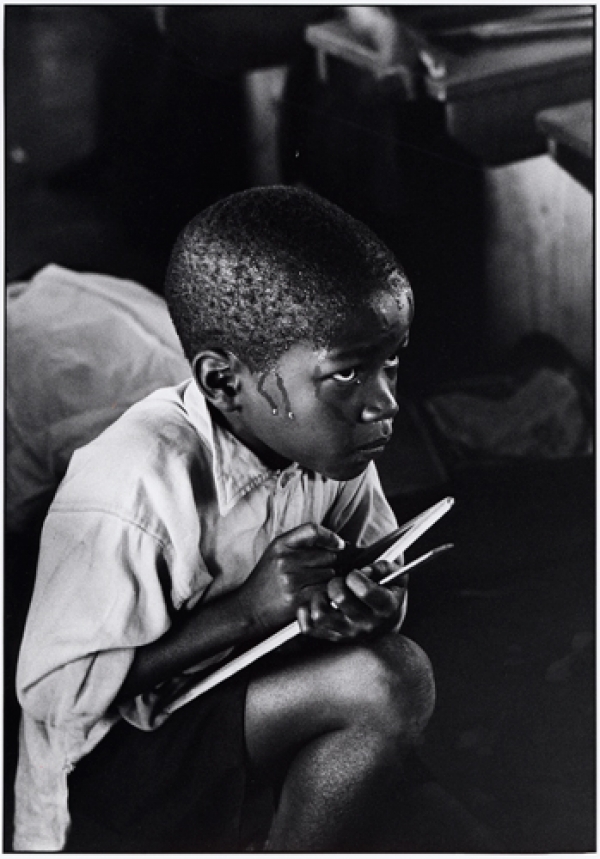

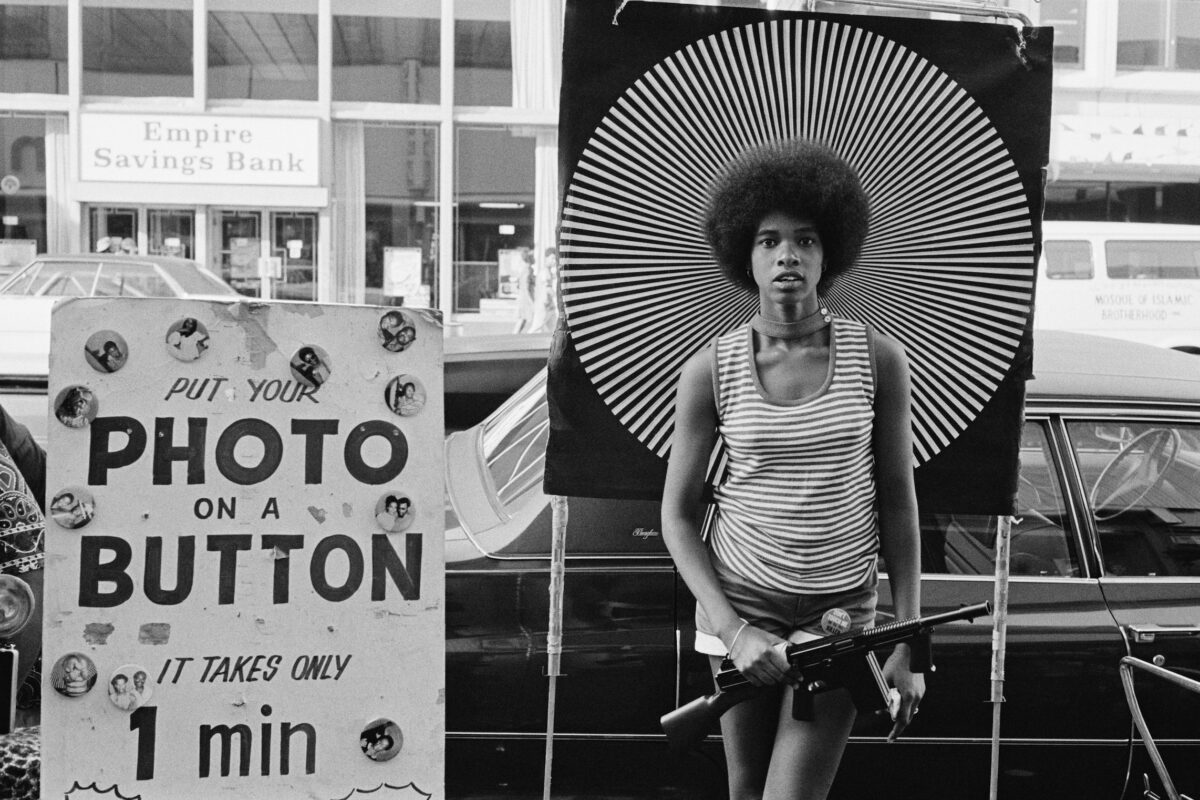

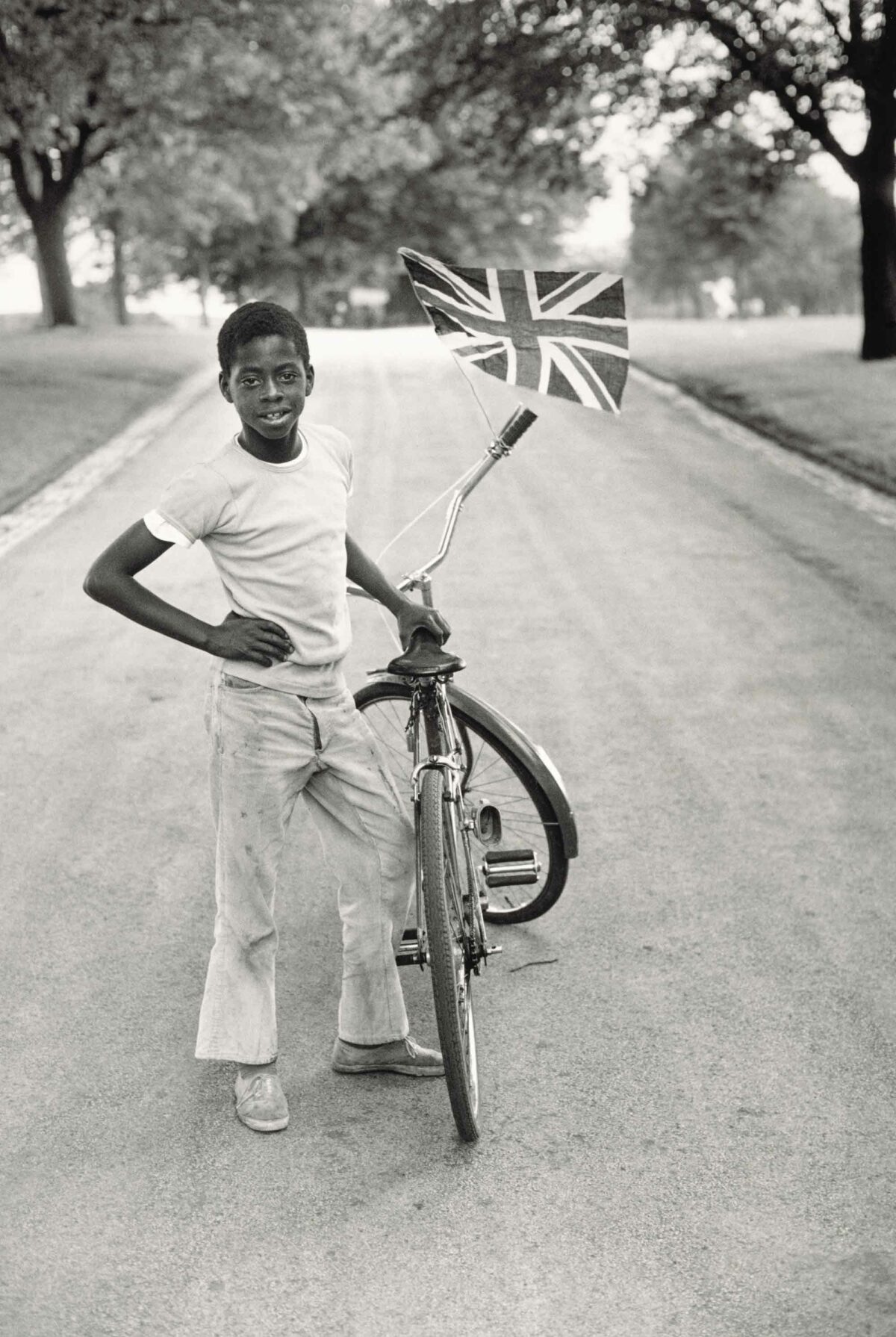

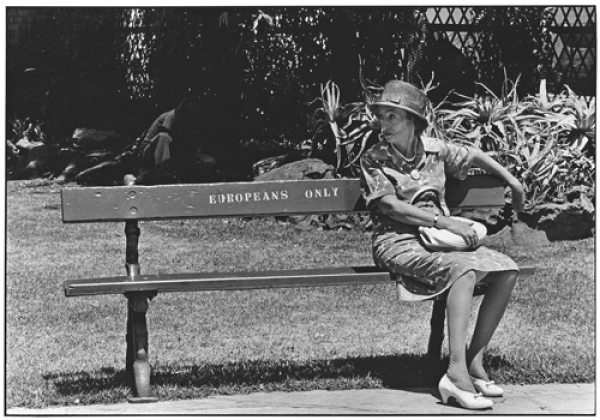

The essence of his work, House of Bondage, was published as a book in 1967. This exhibition presents the photographs as Cole would have wanted, uncropped, with his captions. More importantly, they reveal a photographer, not simply a man with a message. Cole’s model was Henri Cartier-Bresson, and the political power of Cole’s images resides precisely in his commitment to portraying lives as lived, in a place where even the ordinary moments are decisive. Among the many powerful images of discrimination and displacement, I am more drawn to quiet pictures that convey the texture of apartheid from the inside: two black women eating grapes on the lawn of a middle-class house, just beyond a wall bordering the front garden. It seems so benign, but Cole tells us that as servants, blacks were not allowed to receive any visitors on their employers’ premises, and so had to meet people away from the houses, near the street. Closer to invisibility. Piercing this invisibility was Cole’s great achievement.