Unlike most photographers, Emi Anrakuji isn’t content to use the camera simply as a tool to convey her own, subjective view of the world; instead, in her hands, the camera becomes a strident, and at times less than cooperative, witness to the very tenuousness of perception itself. Such a metaphysical, and ultimately compelling, approach to making art comes honestly to the Tokyo-based artist, who suffered a debilitating brain illness when she was in her 20s that left her blind in one eye. Today the 51-year-old artist can see, though her vision there is severely impaired. Fortunately, accurate vision is less a prerequisite for making good self-portraiture than having the courage to look.

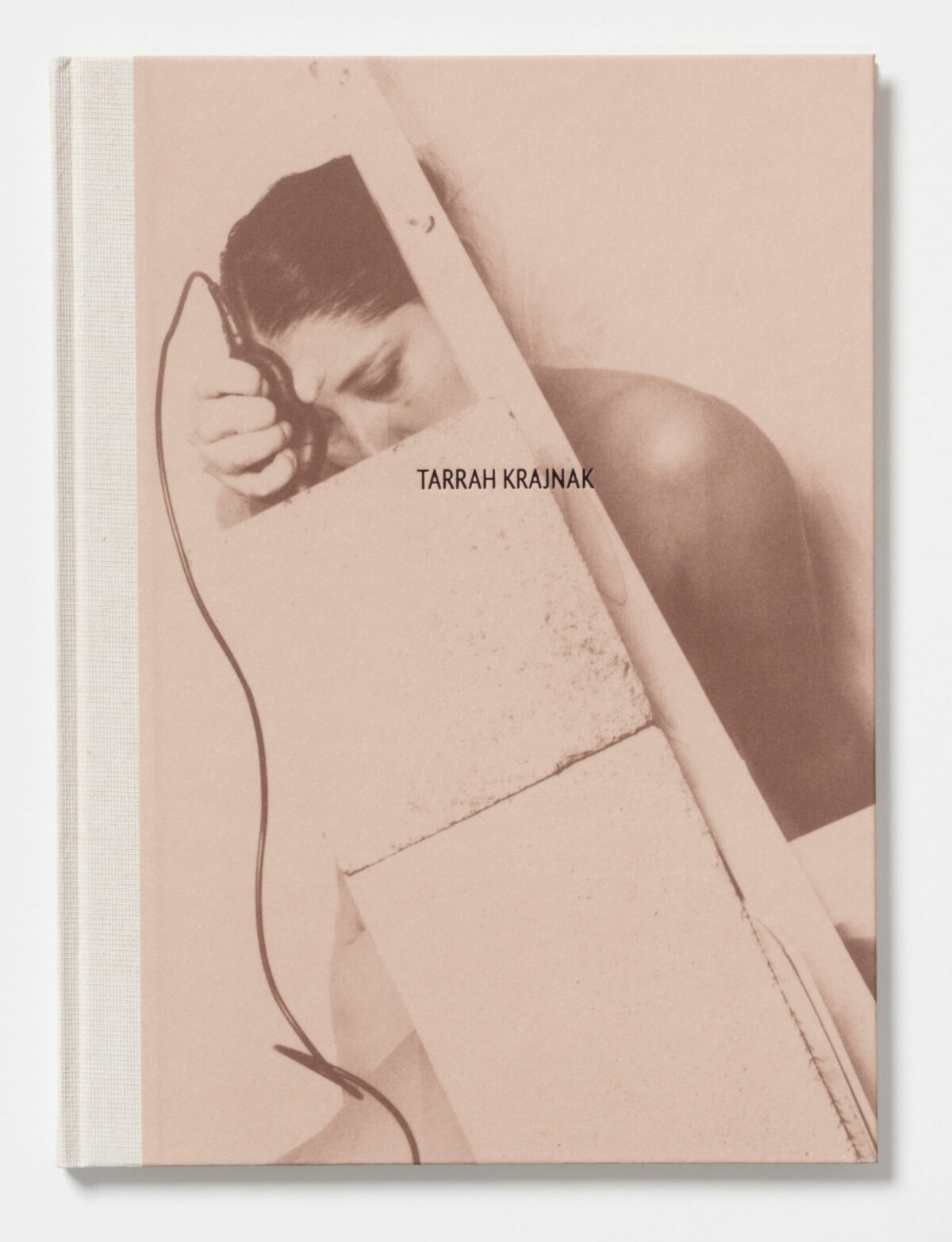

These simple, pleasing pictures, on view at Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery through May 30, achieve a great deal of dynamic motion (and convey more than a little sexual tension) via a few basic formal and compositional conceits: the use of disorienting diagonals; overexposed and washed-out back-lighting; starkly printed contrasts; and a slew of reflections in both mirrors and polished surfaces. Objects become indistinct — forcing us to look, and look again. In one image, Anrakuji holds a huge pair of scissors in one hand, balances her weight on one leg, and raises the other — we presume she’s about to trim her own pubic hair, albeit rather precariously. It would be nice if we could read her facial expression while she’s poised in this act, but, alas, her own ample hair blocks her face almost completely from the camera’s view. In another image, we see the same scissors reflected in what seems to be a circular shaving mirror. The scissors appear smaller this time, yet somehow more menacing. Anrakuji shot all these scenes in two locations — a hotel room, and friend’s borrowed New York apartment — and the highly confined domestic spaces add a frisson of both lived-in familiarity and indistinct foreboding.

The shot that distills Arakuji’s potent ability to fuse larger social imagination and private space (read: what the media likes us to think women do when they’re alone, and what they really do when they’re alone) is a single, vertical shot of Anrakuji’s naked body seen from the breasts down. She kneels on a bed, dangling a series of ball-shaped objects before her torso, and, at the point where her thighs meet, or rather, don’t (the artist is quite thin), a small shaft of shadow appears that, believe it or not, reads just like the glinting blade of an unsheathed sword. After blinking once or twice, we can convince ourselves that this shiny, phallic mirage is of course the object of our imagination, but too late — a “transgression” has already stuck in our minds: A woman, left alone, in a hotel room, has been allowed to see her own body however she chooses. Good thing the camera was there, to play along.