In Misunderstandings (A Theory of Photography), the conceptual artist Mel Bochner quoted the Encyclopedia Britannica to the effect that photography cannot record abstract ideas. I take it as axiomatic that a large segment of contemporary photography traffics in nothing but abstract ideas. That is, the major preoccupations of the work lie outside the frame. These include: the production, distribution, exchange, use, history and technology of images, as well as the attribution of significance and the forms of desire to which they minister. Many of these photographs aren’t aesthetically pleasing, but it doesn’t mean they’re dumb.

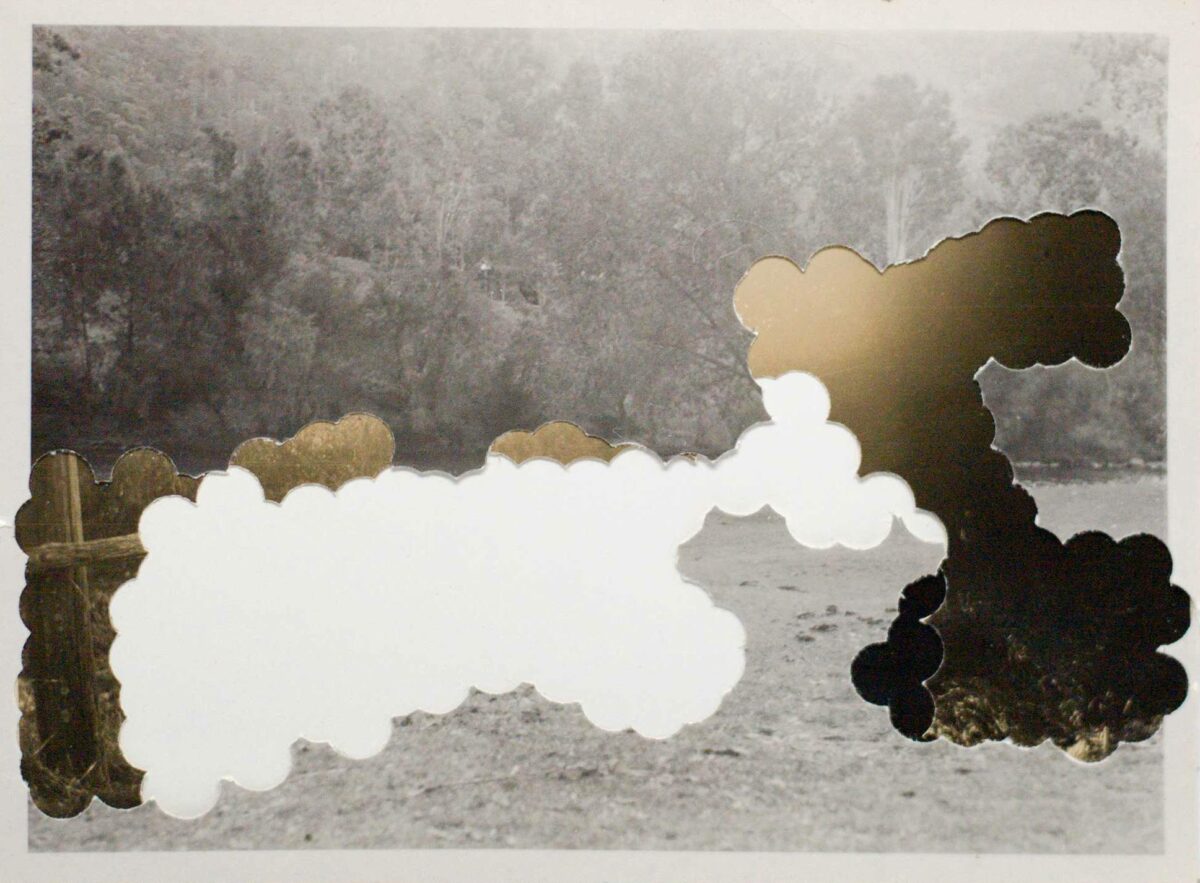

Case in point: the work of Eileen Quinlan. A series from 2005 titled “Smoke and Mirrors” said it all. The idea behind the work seemed to be that photography (even when it aspired to promote a Concretist new vision) was a kind of parlor game in which the illusion of the images was more engrossing than their denotative contents. Some of the pictures appeared just plain clumsy and others like experiments in geometric abstraction gone wrong. The photographs clearly had an ulterior motive, but what’s more, the bad began to look weirdly good. That’s what made the work satisfying: it wasn’t just a thesis but a thing, always funnier, funkier and more unsettling than any intellectualizing description.

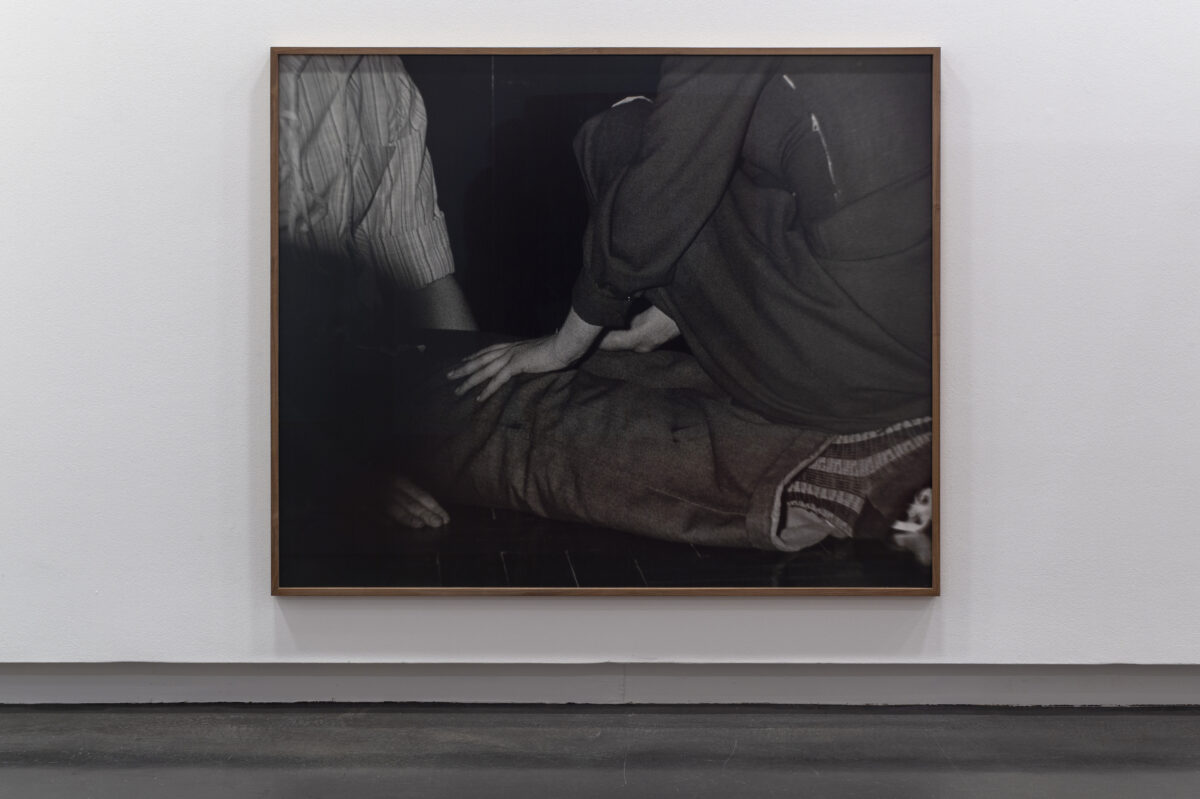

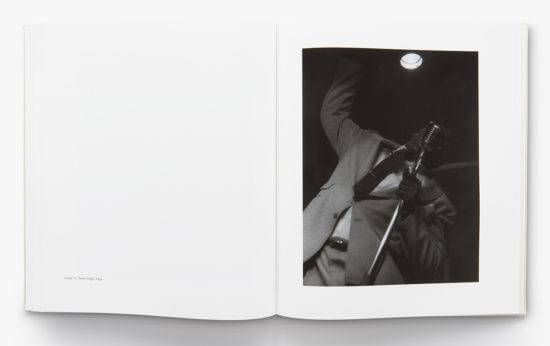

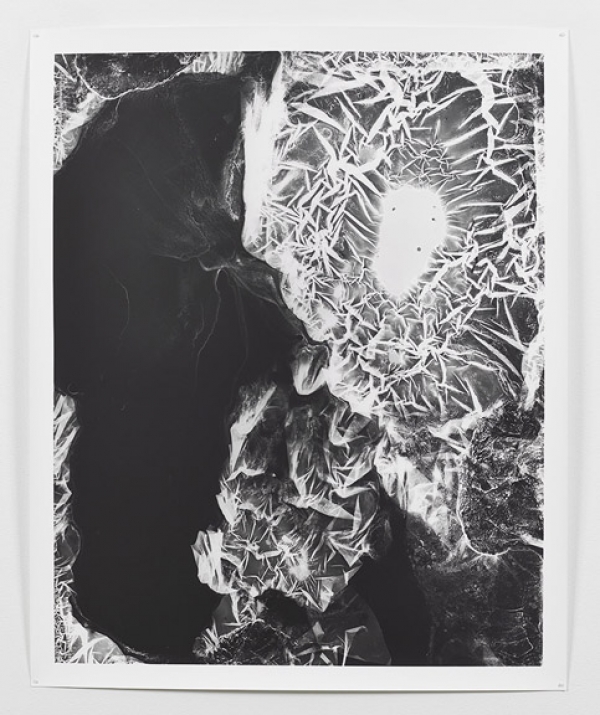

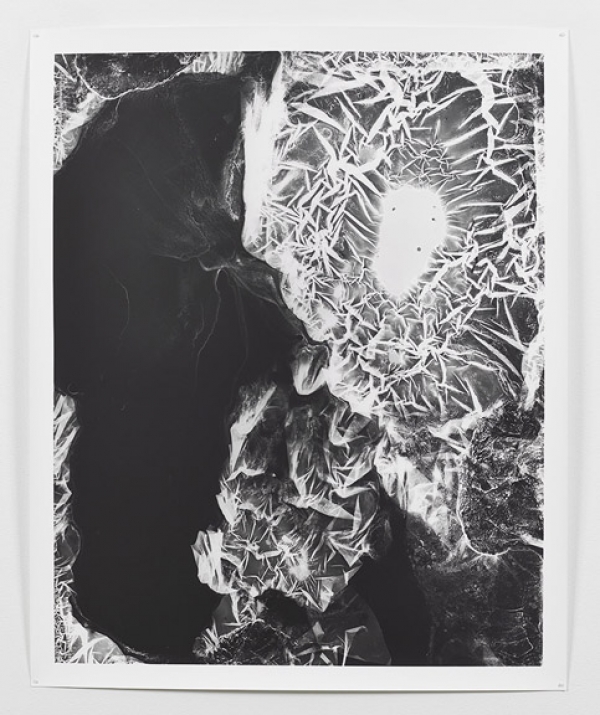

The exhibition at Miguel Abreu through December 8, Curtains, takes these preoccupations several steps farther. (Quinlan’s work is also included in MoMA’s New Photography 13, on view through January 6.) The 24 silver prints constitute an elegy for the medium: images made from damaged or decayed negatives, high-contrast portraits that border on fashion and rephotographings of snapshots pinned to a wall. Many of the images record chemical process events and “performances,” that is, Quinlan’s interventions on the negatives, all of which reveal the astonishing depth and complexity of two dimensions done in black and white. The word curtains seems to refer to a withdrawal from conventional expectations of photography and more narrowly to analogue media – it’s curtains for the wet world! The paradox of all elegies, however, is that they make us realize how much we miss what’s passing and why we can’t let it go. From this series it seems that Quinlan, for the time being, has every intention of hanging on fiercely.