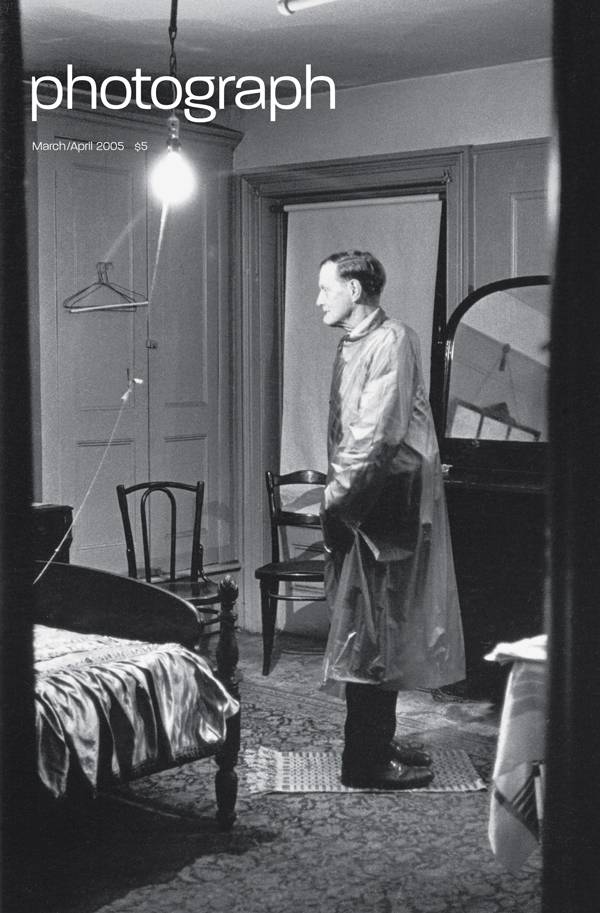

No matter how deep the inroads of cultural theory, no matter how many Jeff Walls, Christopher Williams, and articles in October appear, Diane Arbus won’t go away. Concept-free, she has the dark photographic gift that still thrills the millions, the uncomfortable invasiveness, the perpetually adolescent, socially maladapted, alienation-fueled, identity (and sex) obsessed vision that continues to grant permission for a pornography of looking, as long as there is a bourgeois society that raises its children, especially its girls, to be polite. But this description, true as it might be, is based largely on a group of notorious and familiar images. Arbus’s fascination with unbridgeable difference – lives she could never enter into no matter how much she might have desired, extreme outposts of consciousness, such as transvestites, side show performers and people with disabilities – is what people remember and keep coming back to. And that sense of strangeness extended to almost everything she shot.

But the impression is based on iconic, sensational images. A wider selection of her pictures modifies the Arbus story in fascinating ways. With a trove of images to draw on, curator Jeff Rosenheim offers a much richer view of the photographer’s work than any previous exhibition, even though he covers only the first seven years of her artistic practice. It does seem a stretch, however, to title the exhibition “in the beginning” when Arbus’s career was so short. Doubly so, since Rosenheim deliberately scrambles the chronology by displaying the photos on freestanding panels that impart a hall-of-mirrors discontinuity to her oeuvre. Indeed, the exhibition, on view at the Met Breuer through November 27, looks at first a bit sepulchral, with phalanxes of standing stones, but the arrangement grows on you, because you wind up wandering among the images and gaining a sense that you are inside Arbus’s head, really seeing through her eyes.

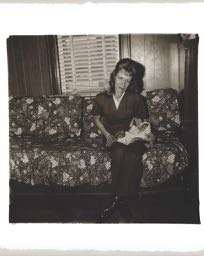

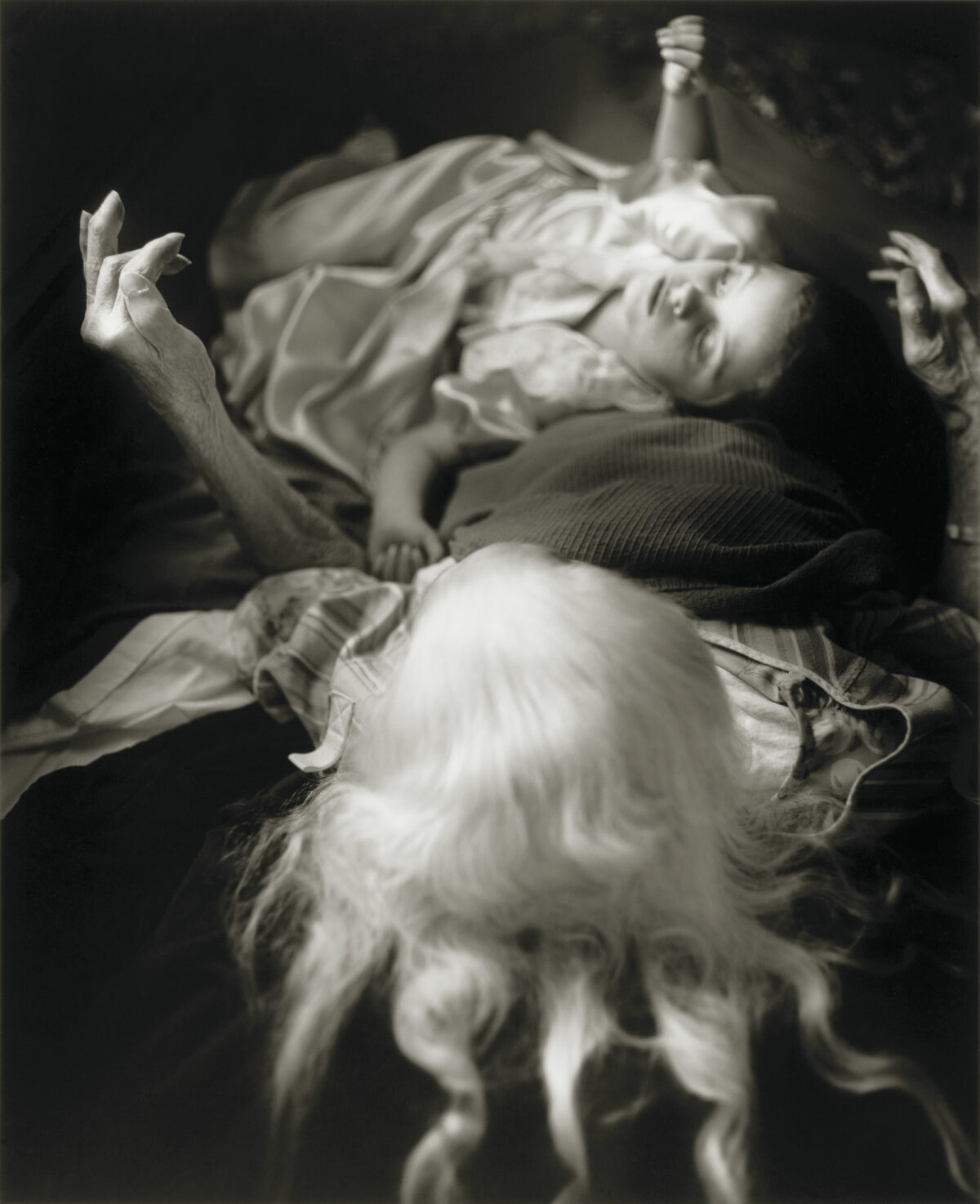

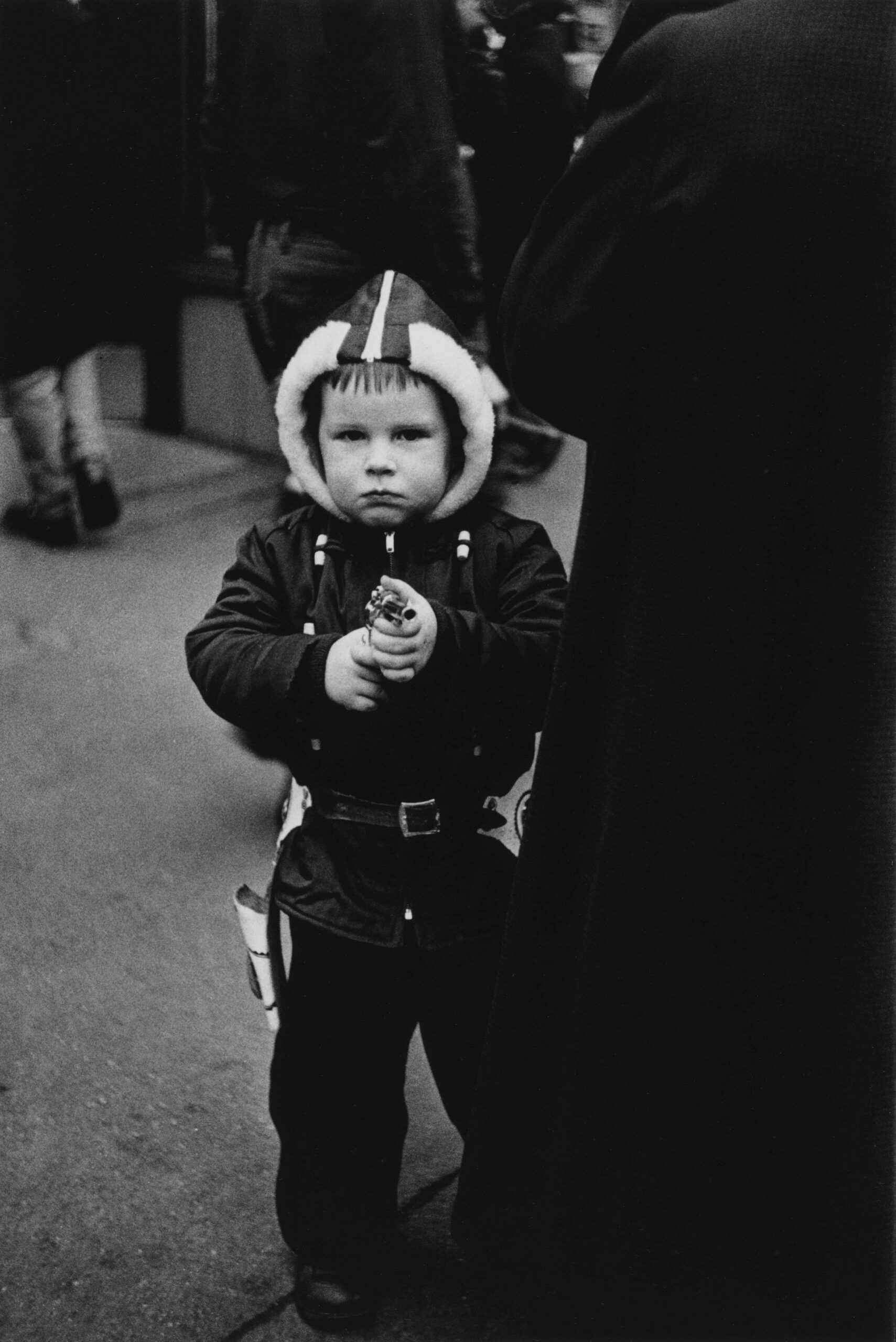

What did she see? Mostly, with some exceptions, people. She cultivated a sense of incongruity between the way people see themselves and the way the camera sees them, or between the way they stage themselves (the backwards man, nudists, tattooed Jack Dracula) and the way they really exist. Hence the sense that everyone is not merely performing but attempting to negotiate appearances, a full-time existential challenge. For a photographer, that’s the place where pathos and fear both reside.

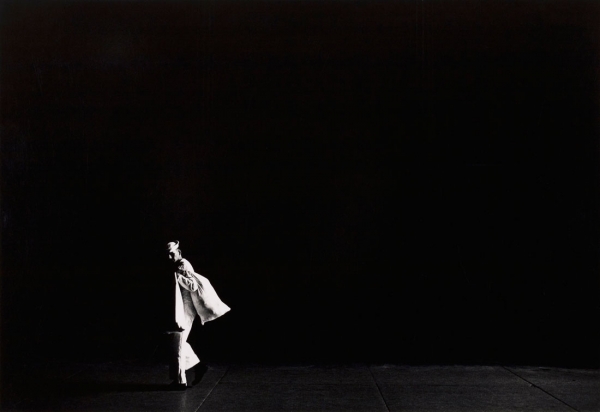

Yet the simplest portraits seem to seek –and reveal –more than that anxiety. In a slightly out of focus but otherwise normal street portrait of a matronly woman in white gloves and purse, Arbus seems to be asking an obvious question: why am I taking this? It could be because in that upper class normality she saw an image of what she might have been on track to become, given her upbringing, and found it the strangest thing of all. Likewise her luminous early pictures of children, especially one of a girl in profile, looking upward. Of course, Helen Leavitt owns this subject, children on the street, but Arbus was focused on something else besides their games. It looks at first glance like innocence, but really it’s the sense of a child’s inwardness, of its being profoundly elsewhere and unlooked at. Arbus herself would have understood that as an absolute form of freedom.