In 1993, just four years after the Tiananmen Square protests, a young photographer named RongRong arrived in Beijing from Fujian Province. Seeking a community of artists and negligible rent, he settled in a small slum on the outskirts of the city that had taken up the moniker of “Beijing East Village.” There he encountered Zhang Huan, Ma Liuming, Zhu Ming, and other artists who were pushing the boundaries of performance art with harrowing acts that often led to clashes with the local police. RongRong had found his subject matter, taking it upon himself to document the people and the theatrics long before they were recognized as hallmarks of Chinese contemporary art history.

The 40 photographs in this exhibition, on view through October 12, capture RongRong’s contribution to the Beijing East Village art scene, demonstrating that he was as much a participant as an observer. Each photograph is paired with captions from the photographer’s diary, which has been published by the Walther Collection as a beautiful book that will surely be essential reading for anyone seeking to learn more about this period in Chinese art.

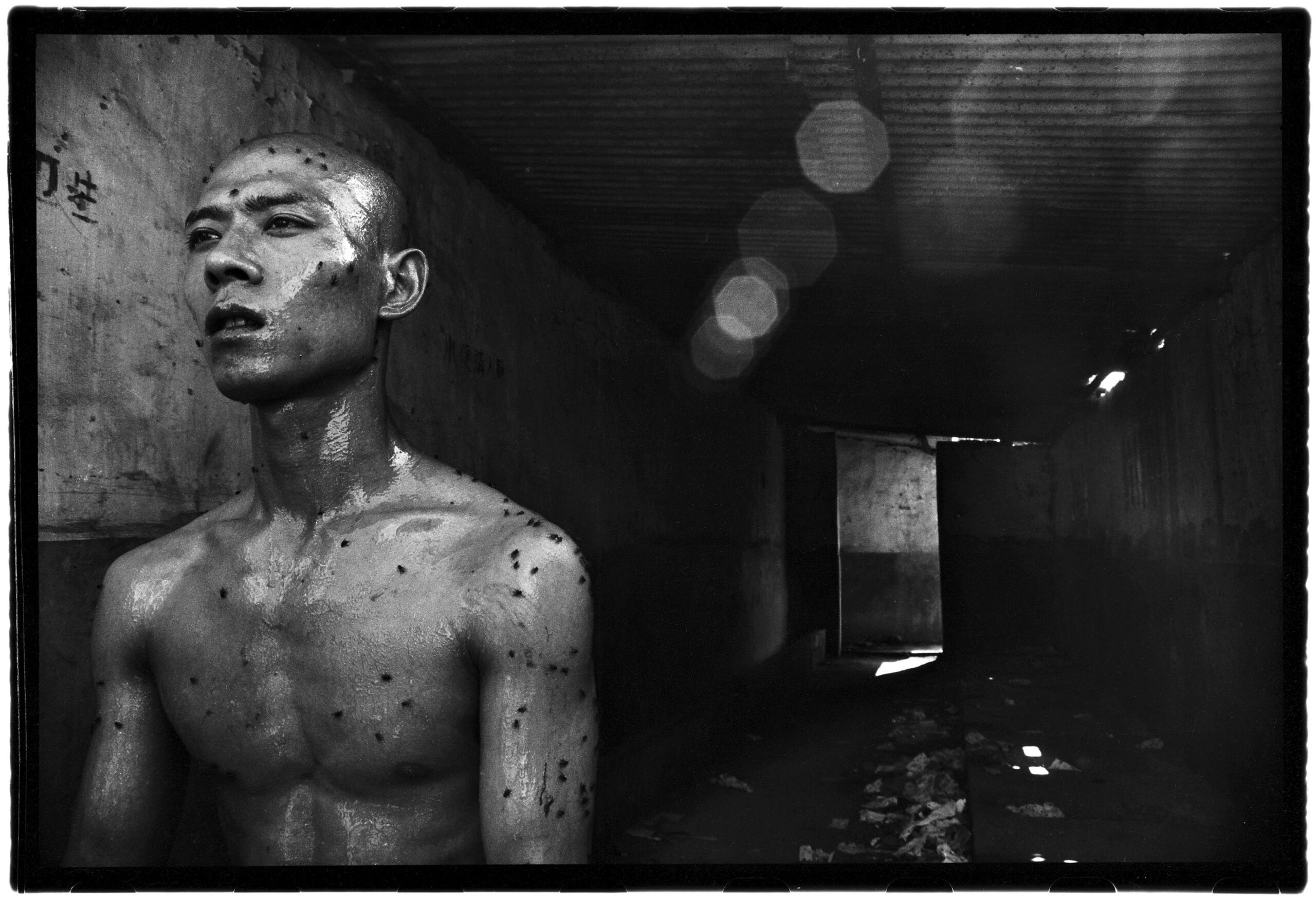

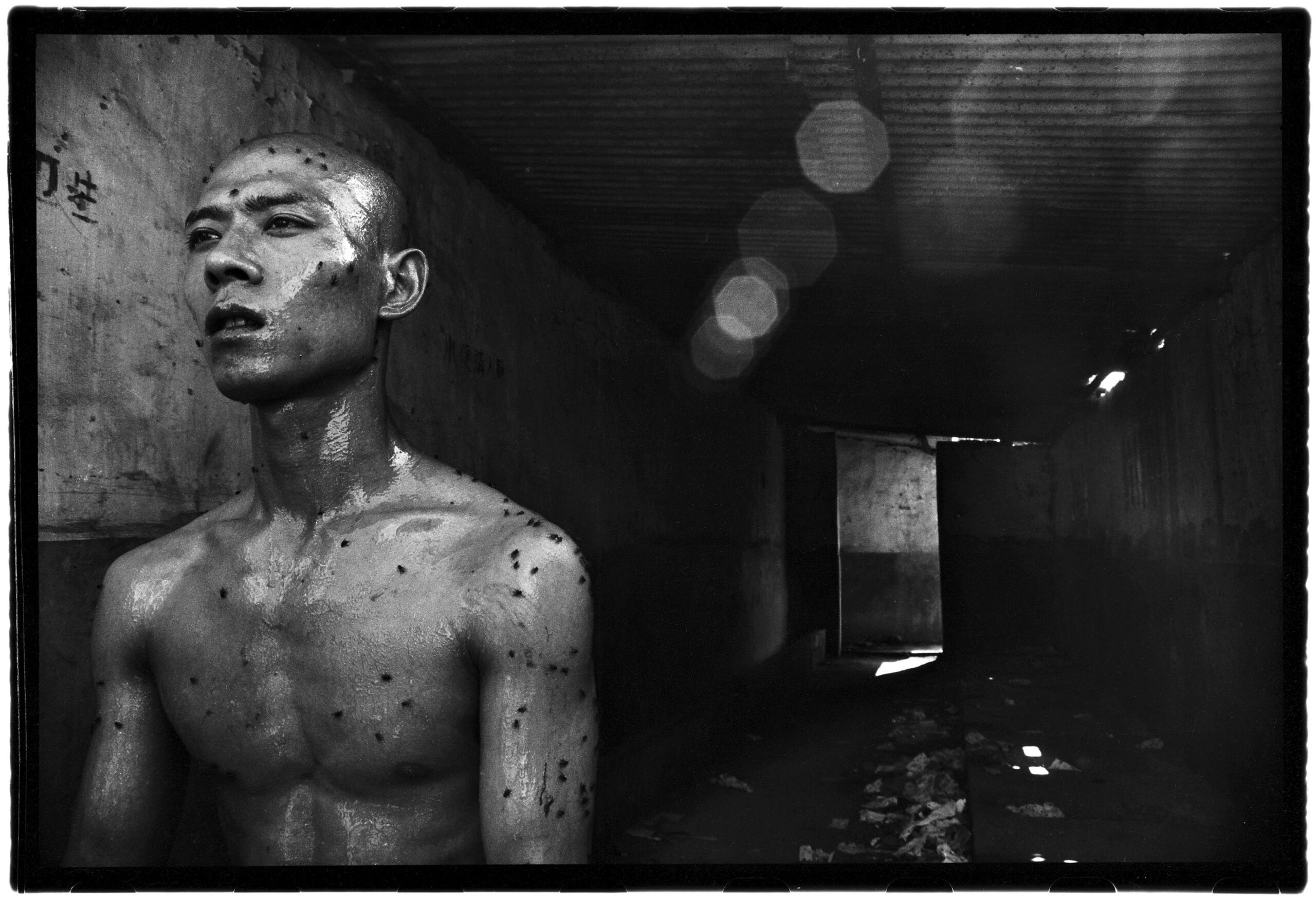

For example, RongRong captured Zhang Huan’s act of sitting motionless in a putrid public latrine for an afternoon, covered in fish oil so that flies stuck to his skin. Zhang Huan is now world famous, exhibiting with Pace Gallery, but this early work is particularly infamous and would have been lost to history without RongRong’s iconic photograph. It is clear that the presence of a photographer in this community inspired the artists to take such actions, knowing that their work would not be lost, despite the fact that there was no audience for such work at the time.

RongRong has since gone on to have a major career as a photographer, not only documenting other artists but creating haunting images himself in collaboration with his wife, Inri. He also founded the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing, which promotes the medium for new audiences. But this early work is perhaps his most important, given its relationship to the roots of Chinese contemporary art, which surely would have been forgotten and erased without his contribution. In this case, his words as well as his images recall a period before the art market and the public took notice. For this reason, they are a thrilling reminder of a time when experimentation ruled all and when artists were willing to take risks because they had nothing to lose.