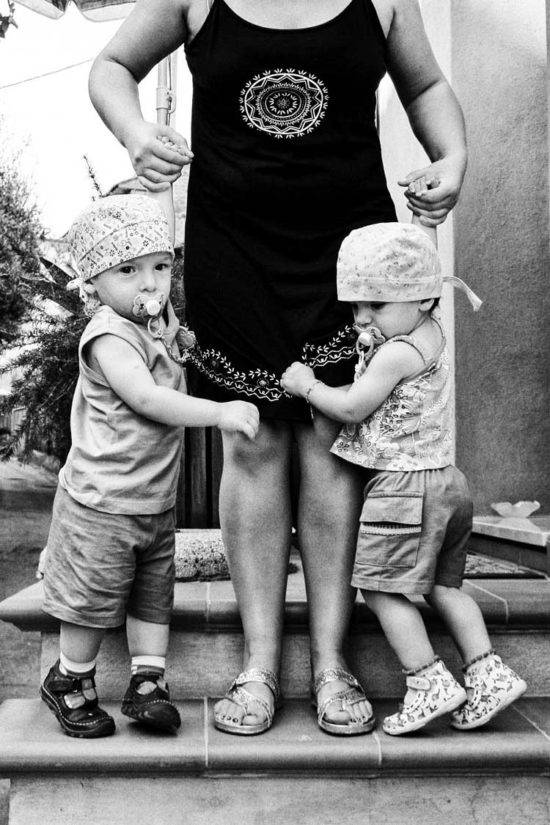

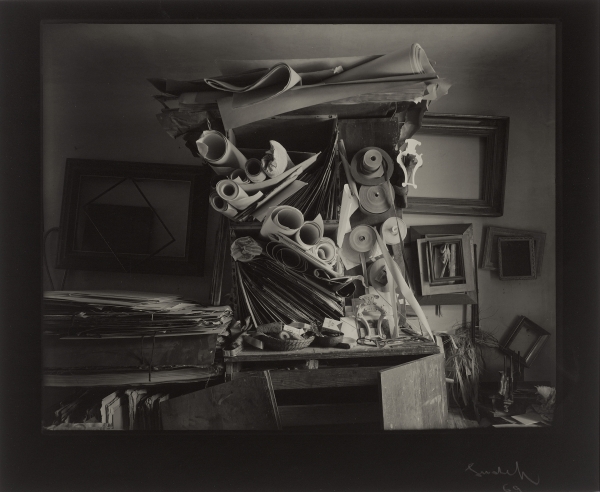

For this exhibition at the Denny Gallery through February 2, Danielle Durchslag, a young New York-based artist, translated into collage photographs of relatives whose identities and memories have slipped through the cracks of her family history. The small collages — 4×5 to 11×15 inches – are made of tiny pieces of heavy drawing paper tinted in sepia or gray tones. Occasional flecks of white paper act as highlights and illumination.

Durchslag’s works are deeply disorienting, because they so accurately reproduce the formal aspects of a photograph. Only after closer observation does it become clear that no real people have impressed their likenesses on photosensitive material. The initial illusion is possible due to Durchslag’s remarkable craft and capacity to faithfully reproduce photographic light and tones with her small pieces of paper. In addition, she places some of the works on antique photo album pages and in classic late 19th-century mats.

Her collages are like exquisite marzipan fruits, perfectly delightful and very enjoyable as long as you come to them with a craving for almond paste and not for apples and peaches. Being a photography lover, I found myself squinting in front of the images, hoping for the actual photographs to appear. In A Short History of Photography, Walter Benjamin wrote that one of the great differences between photographic and painted portraits of people whose identities have been forgotten is that, for the photographs, there are factors that stop them from “fading into art.” In other words, we cannot forget that photographic images were generated by living, breathing beings whose personalities we may still be able to sense if we look closely enough.

Durchslag’s project recalls the Grimm Brothers’ fairytale The Seven Crows, in which a girl has to overcome incredibly difficult tasks to free her brothers from a parental curse that has transformed them into birds. One can’t help but sense the love and care that Durchslag put into these pieces. But the best non-photographic images of family are the ones that tell us about the emotions and attitudes of the maker—one thinks of Rembrandt and Picasso. Maybe this is Durchslag’s goal: to convey the experience of staring at the likeness of a blood relative whom she will never know. But by making the images so close to the photographs, she makes us long for the photographs themselves.