Like many of America’s finest photographers, Curran Hatleberg has heard the call of the open road. And for the past 10 years, he’s answered it, photographing the country in ways both unexpected and unsettling.

No place, so far, has held his attention quite like Humboldt County, California, where he felt compelled to live for six months in 2014. Looking at his series, Lost Coast, on view at Higher Pictures through June 18, will leave little question why.

With its forested mountains and expansive coastline, the county’s grand topography is uniquely capable of shouldering Hatleberg’s grand vision of America — a place, as he depicts it, situated on the precipice between beauty and ugliness, creation and destruction, fiction and harsh reality.

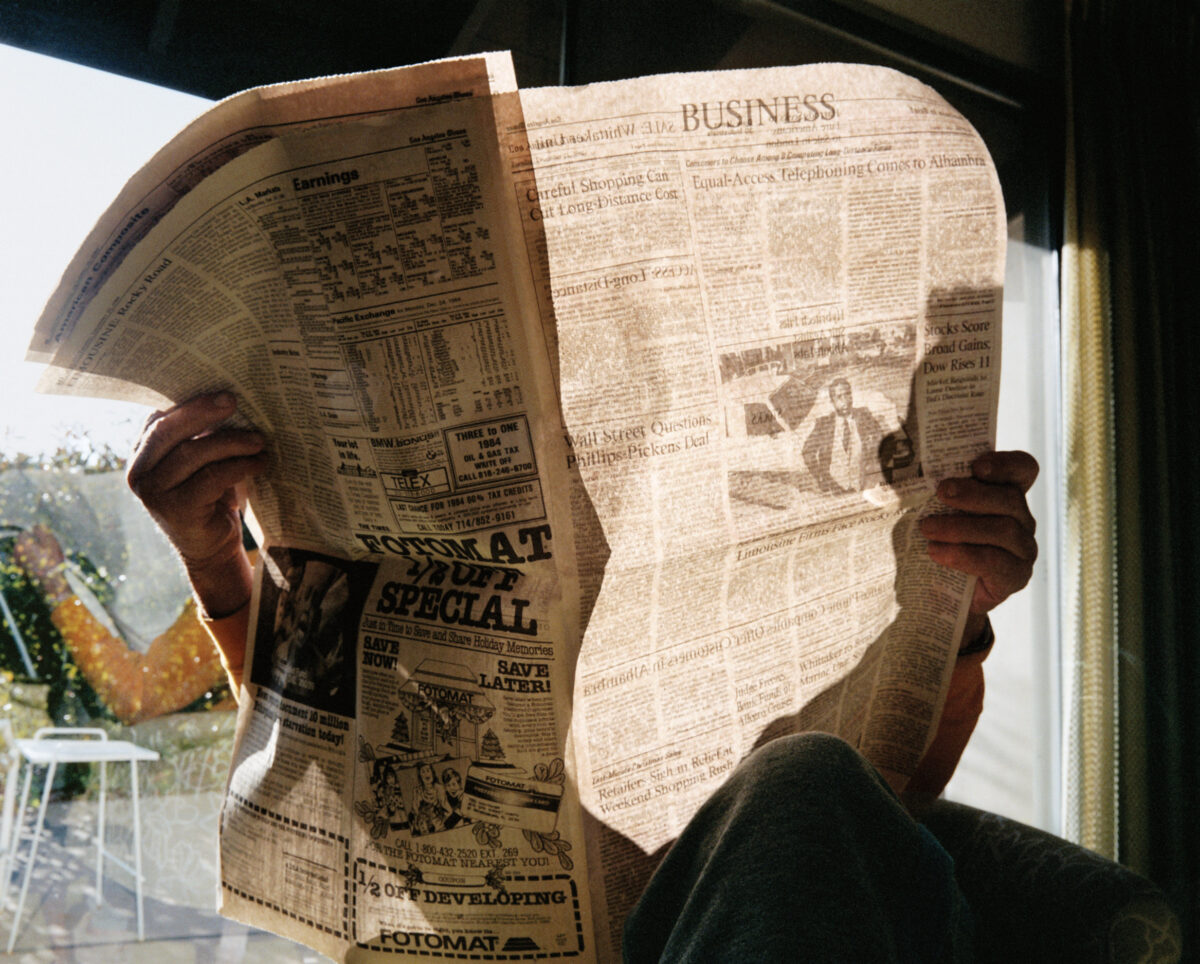

His photographs, in keeping with that vision, are as epic as they are enigmatic. Hung with less than an inch between them in a continuous row snaking through Higher Pictures’ cozy, single-room gallery, the 12 x 15-inch prints place disparate elements in beguiling proximity. Children and puppies contrast with a burnt-down home, pink flowers clash with dead vegetation, and, in nearly every frame, the precarious existence of a local population experiencing the effects of industrial decline feels at odds with the breathtaking grandeur of the dreamlike surroundings, often bathed in golden light.

Hatleberg’s photos succeed as social documentary, but to see them only that way ignores their freewheeling poetry, and their lack of any sort of useable, concrete information. The photos are untitled, and while the gallery’s press material gives a basic description of the exhibition’s subject, some of the most fundamental questions about this work remain unanswered. Who are the people in these photographs? What’s happening to them? And most importantly, how are we meant to feel about them?

Just when you think you may have found some clues among the more straightforward shots of small-town life, Hatleberg throws a confounding curveball: The solitary, matronly woman striking a strangely sensual pose in the night; the pale man, back to the camera, getting his head shaved; the woman collapsed on a sidewalk beside a bicycle. Are these moments of sly ridicule or grim observations of an otherworldly reality? In the hands of a less talented photographer, these ambiguities might seem like imperfections, but with Hatleberg they strike the viewer as endlessly intriguing and strangely moving mysteries.