What does pain look like? A grimace? A tear? An agonized expression?

For the “standardized patients” depicted in Corinne May Botz’s Bedside Manner, on display at Benrubi Gallery through February 6, that’s a daily concern. It’s their job to dress up and perform assigned illnesses and conditions for medical students, who are learning how to recognize the cause of their suffering and empathize with them.

Pain can manifest itself physically, but it is felt internally. That disconnect makes the job of the standardized patient, one that’s existed since the 1960s and can now be found in dozens of medical schools, especially difficult. It also makes Botz’s images especially interesting.

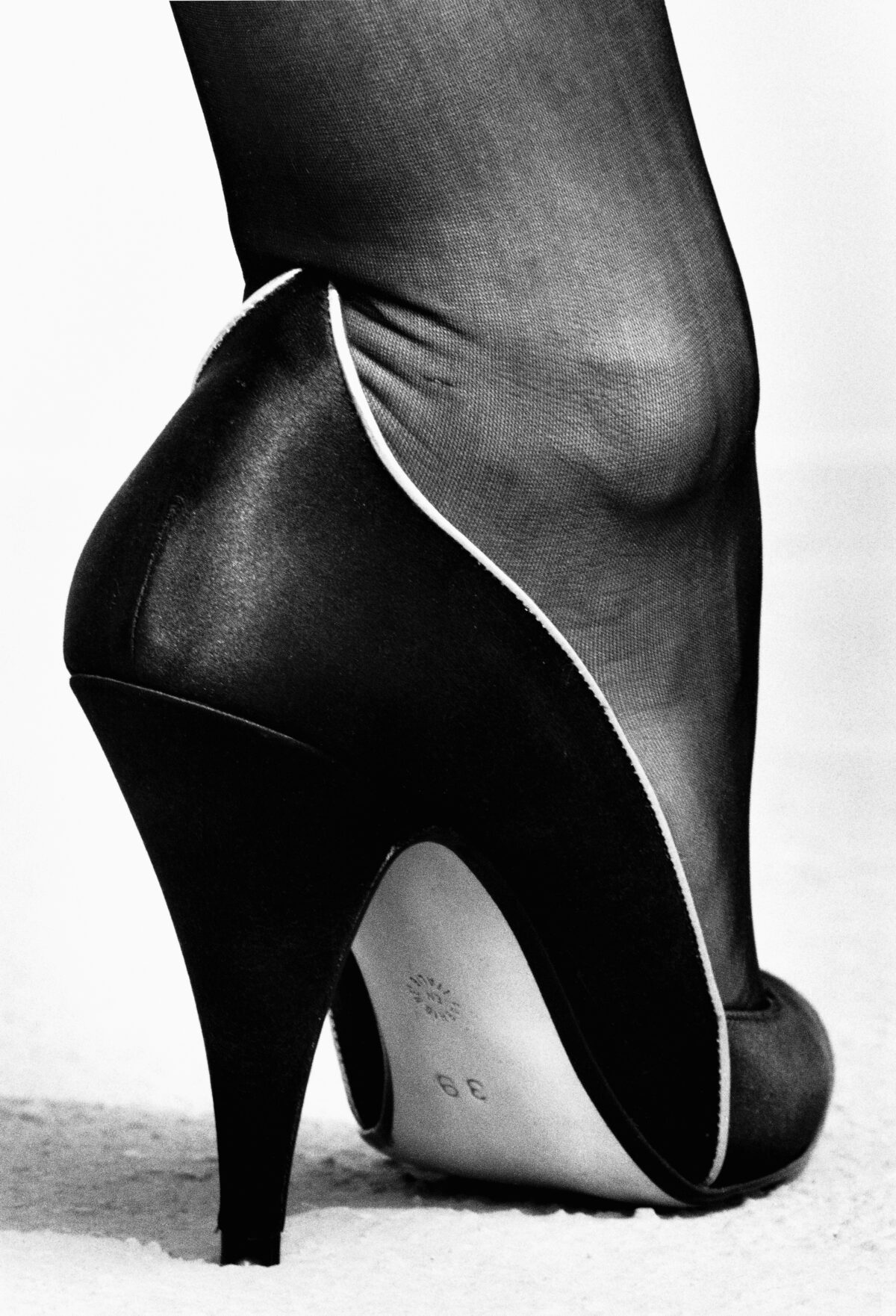

Photography may excel as an accurate mechanism for scientific inquiry, but, in the case of Bedside Manner, it proves to be just as effective at exploring ambiguities. Indeed, the photographs in the series of uninhabited operating rooms and equipment work as a record of the surreal environment where these examinations take place. But her photos are most intriguing when their contents are open-ended, as in the illegible lines of the human face.

What is wrong with these people, one wonders, staring melancholically through a two-way mirror into Botz’s camera, or down at the ground? And how to explain the pang of sympathy one feels for their unidentifiable – and, moreover, false – hurt? What does this say about our reaction to images of real anguish, so abundant in mass media and yet so rarely successful as catalysts for action? Like many photos of people in distress, it’s hard to look at these images, and hard to look away.

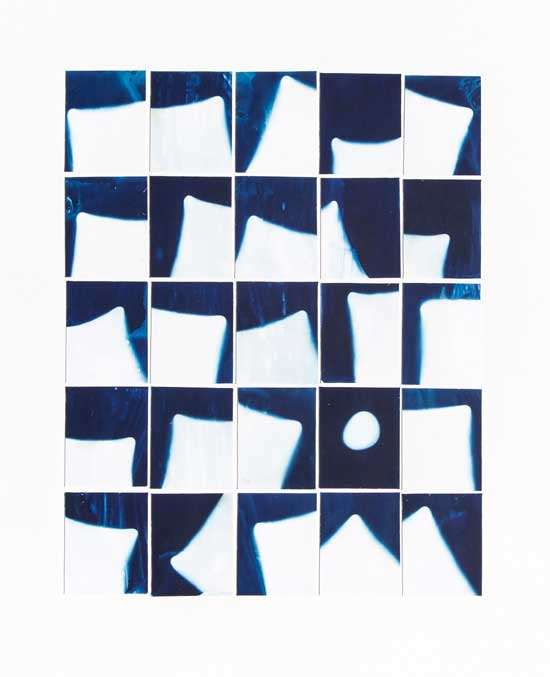

As an artist, Botz is interested in the revelations that emerge when truth and fiction collide, as she showed in a previous series, The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, whose photographs show the insides of 18 mini crime scene dramas based on actual incidents. They were built in the 1940s and 50s by criminologist Frances Glessner Lee, and used to train detectives to evaluate evidence. The photos in Bedside Manner demonstrate a similar attention to light and detail, and they’re equally conceptually rich. Both show that the ways in which we conjure reality can be as revealing as the reality itself.

Through Botz’s lens, even the plastic skin of a small dummy’s hand has uncanny emotive power when shown interacting with the hand of a human being. Botz crops this image close because she recognizes its simple yet profound nature. The careful, gentle touch between them is as strange as it is familiar and universal.