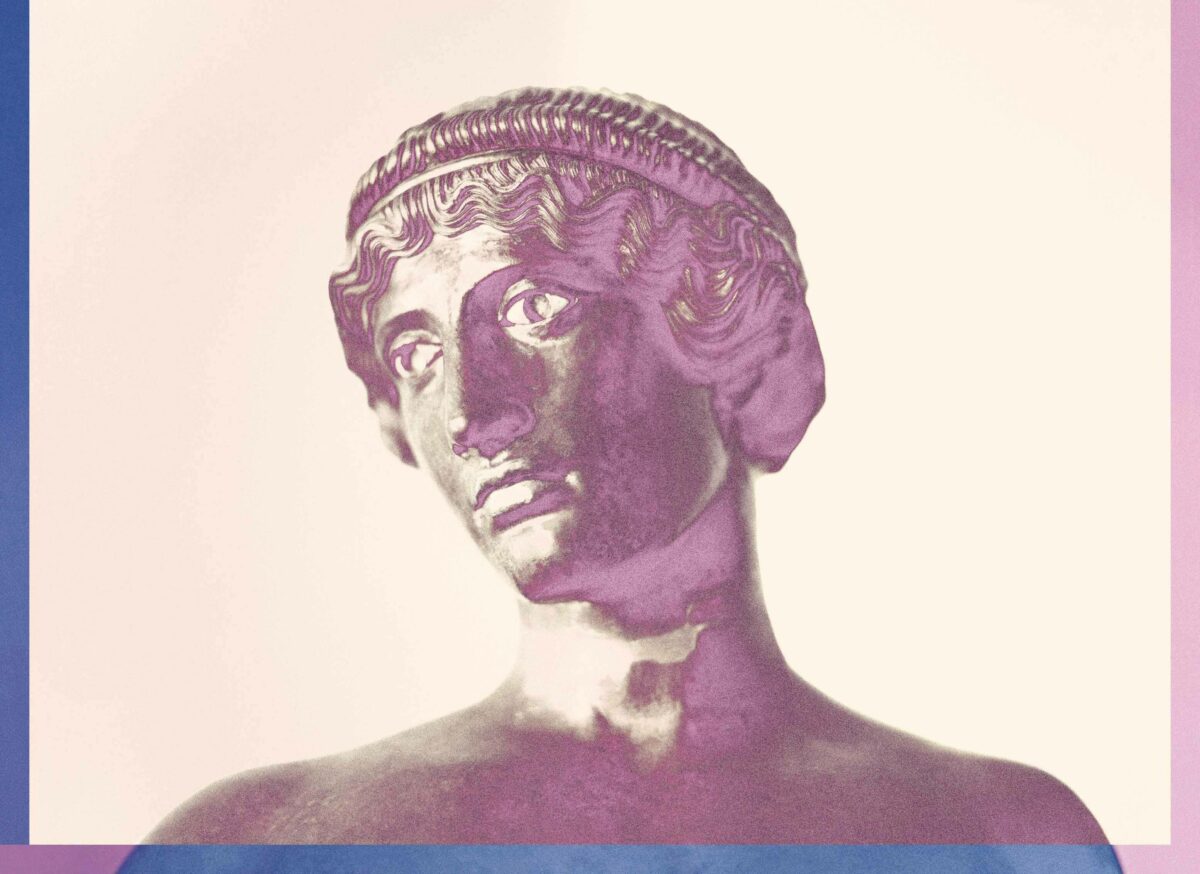

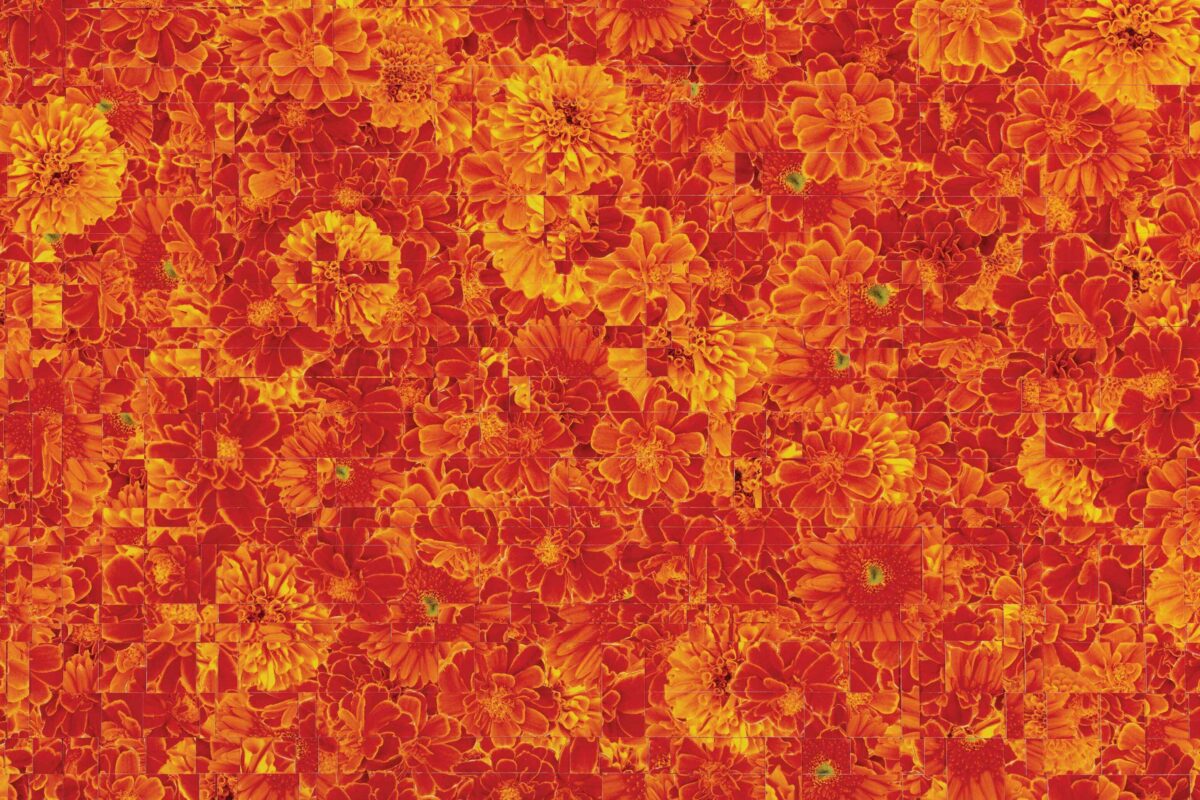

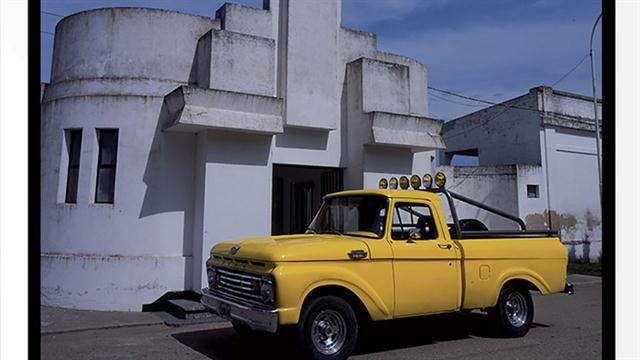

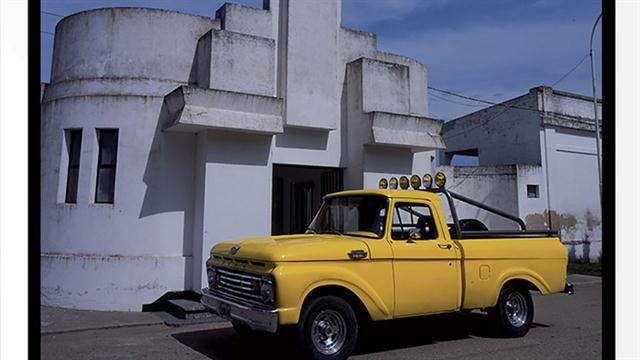

In light of President Obama’s recent visit to Argentina – what we might call a celebration of the new normal vis-à-vis business, human rights, and fast food – this exhibition by two sharp observers of the Buenos Aires street and its social significance seemed especially apt, and sobering. Not that the work is obviously political. Marcos López is Argentina’s answer to Martin Parr, but amped up several notches. He loves plastic swimming pools, famous footballers, bright purple Ford Falcons (also the car of choice for police kidnappings during the Dirty War of the 1970s), and exuberant signage. These small pictures were relatively quiet compared to the overall Pop excitement of much of López’s work, which seems to get younger and gaudier as the rest of us get older. But that’s the way the world of social media is going, and López is never a step behind. The photographs in this exhibition celebrated other qualities that may become less and less evident in a business-friendly Argentina under president Mauricio Macri. The most important is a vernacular resiliency, a local durability that springs from people’s sense of place and class. López seems closest to those with the least, whose gestures toward beauty, entrepreneurial chutzpah, and flights of imagination he celebrates. The artist is the subject of a wonderful video directed by Pepe Tobal in which he visits Ciudad del Este, a border town where everything in the world is traded or smuggled and almost every human type might show up, from a Hezbollah operative to a Buddhist acolyte. For López, it’s the nearest thing to a perfect world, one without borders, trade barriers, or the blandness of good taste.

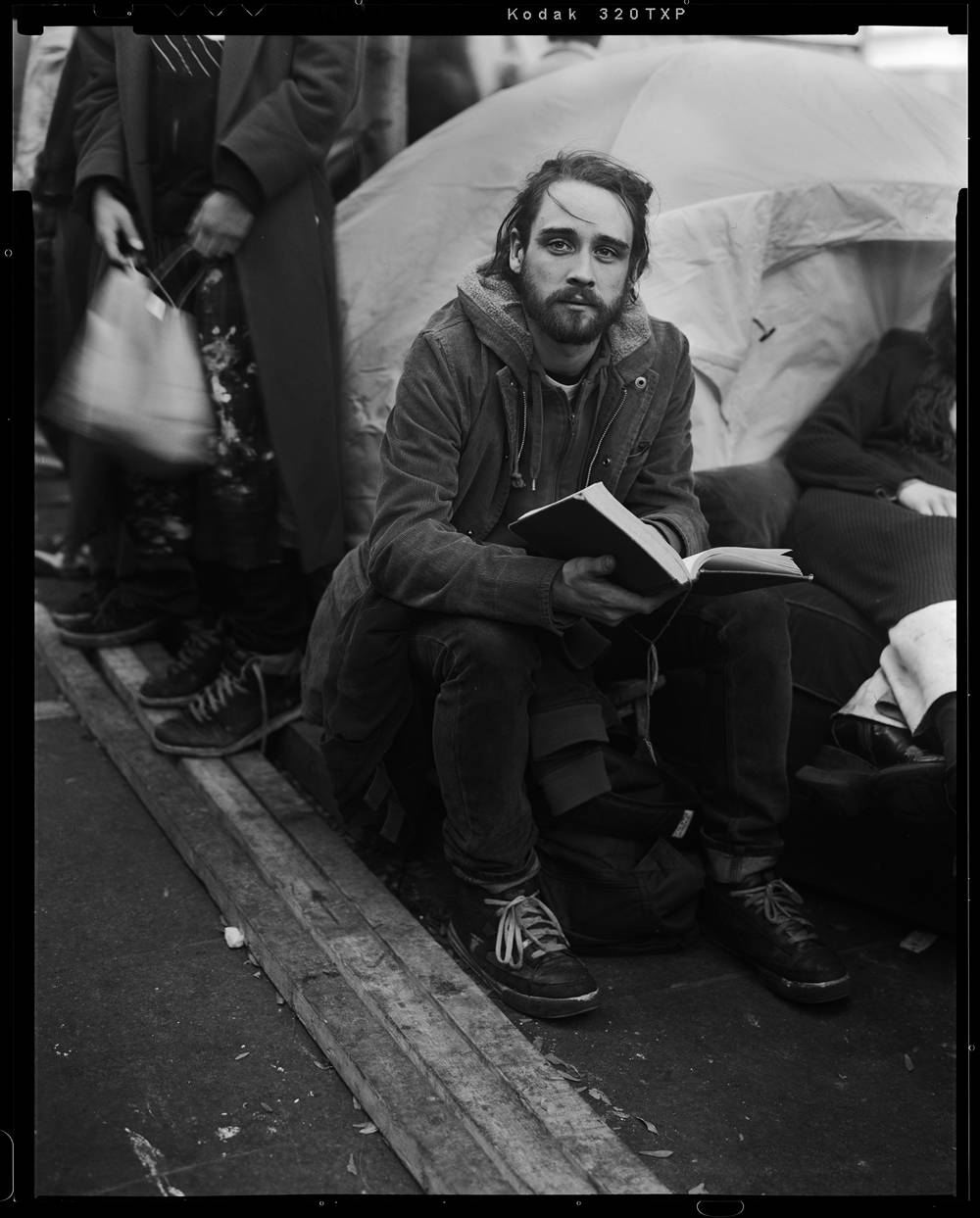

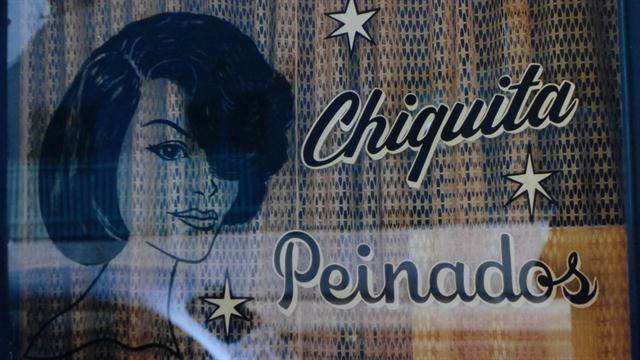

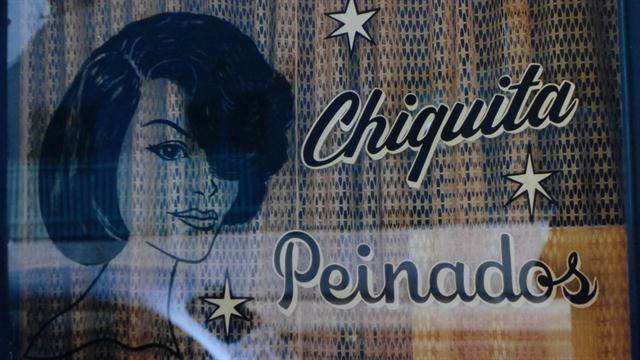

Zuviría’s photographs told a similar but much less festive story. New C-prints from negatives made in the 1980s presented a flaneur’s view of window displays and, of course, signage. There was a bit of Harry Callahan, some Walker Evans, and the bemused pleasure of Luigi Ghirri. In these close ups, the shop and café windows became palimpsests of signifiers, the best poignant in their simplicity – a blue coffee cup, a sign reading Cerrado (“Closed”) hanging inside on a window display of the Argentine flag. Upstairs at the gallery, the mood darkened with a selection of Zuviría’s black-and-white photographs of shuttered storefronts, from a series titled “Siesta Argentina.” Recalling Zoe Leonard’s series of Harlem storefronts, Zuviría’s, however, testified not to gentrification but to the devastating impact of the financial crisis following the devaluation of the peso in 2001. Stark as they were, many of the locales, if not the precise buildings, would have been identifiable to Porteños (natives of Buenos Aires), and some were familiar to this visitor, who had experienced them first-hand in 2003. And more recently. For the series seems as pertinent now as it was a decade ago, in neighborhoods from Villa del Parque to Barracas, where tourists and foreign capital are not likely to penetrate anytime soon. In a cab ride through the city, the taxi driver was asked about the country’s financial ups and downs. He answered, “You can’t really call it a crisis since it has been going on forever.”