Carrie Mae Weems’s subject is the formation, or rather imposition, of identity. Over the course of her long and justly celebrated career, she has repeatedly staged the burden of her particular inheritance of gender and race. Weems often takes straightforward portraits of people of color. But these are usually complicated by bold formal gestures – filters, effacements, blurring – that call attention to the historical assumptions and stereotypes that surround them. In this way, her photographs dramatize the disparity between her subjects and how they are seen; between their human presence and their public representation.

Weems’s 1989 series Colored People, for example, is comprised of portraits of African-American children photographed through various color filters. The effect is piercingly double-edged. On one hand, Weems’s range of tones – sepia, pink, yellow – reveals the absurdity of all racial classification. On the other, her subjects themselves are proof that classification still exists. Weems, in short, is visualizing the human consequence of our biased view of reality. In this concentrated form, both bias and reality are impossible to evade.

This project is continued in Blue Notes and All the Boys, two of the four series that comprise Weems’s present exhibition of photography, text, and video, at Jack Shainman Gallery through December 10.

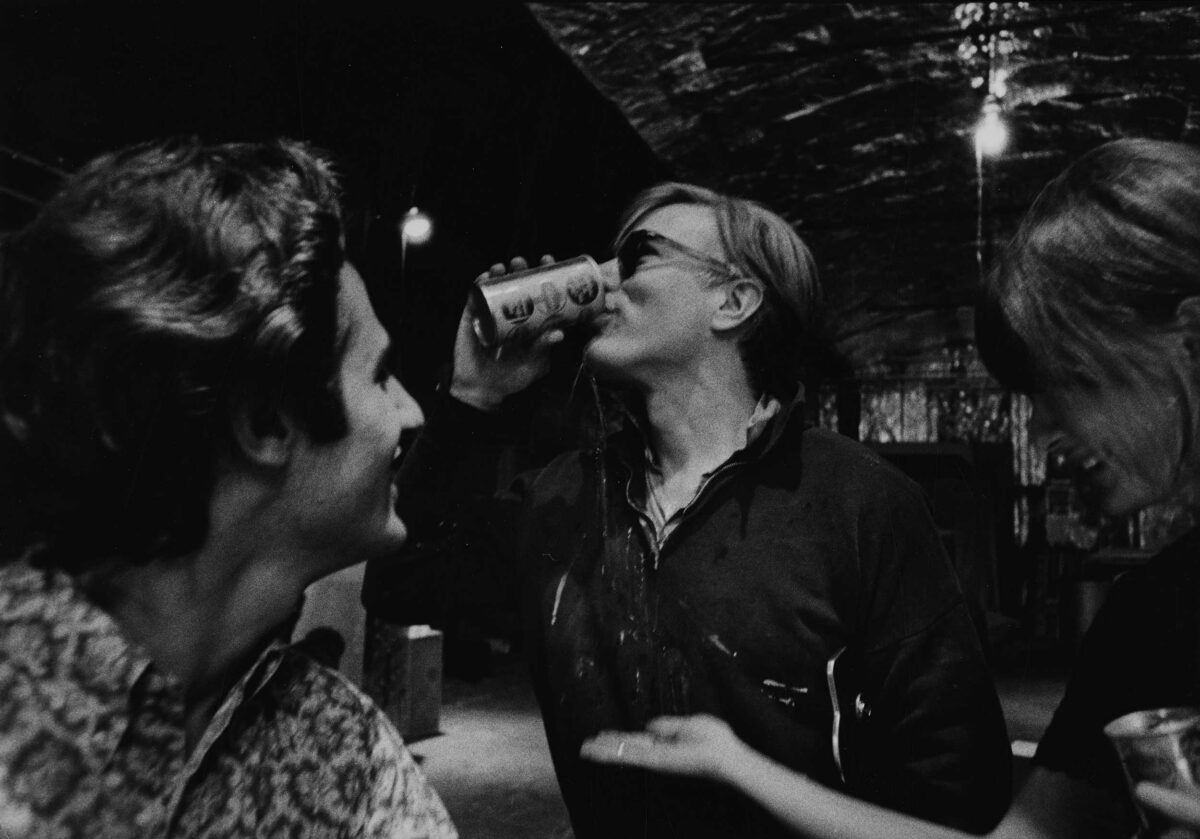

Blue Notes features grainy blue portraits of black artists and back-up dancers whose faces are covered by blocks of solid color. The formal vandalism is at once a reflection and critique of America’s historical erasure of black artists. All the Boys uses a similar technique, to more disturbing effect. This time, Weems photographs several black men in hoodies. Beside them, text panels provide the basic information about ten unarmed black victims of police shootings. It’s a damning gesture. These “usual suspects” may have different personal histories. But, in the end, they are united by the following fact: “Matching the description of the alleged, perpetrator was stopped and/or apprehended, physically engaged, and shot at the scene. Suspect killed. To date, no one has been charged in the matter.”

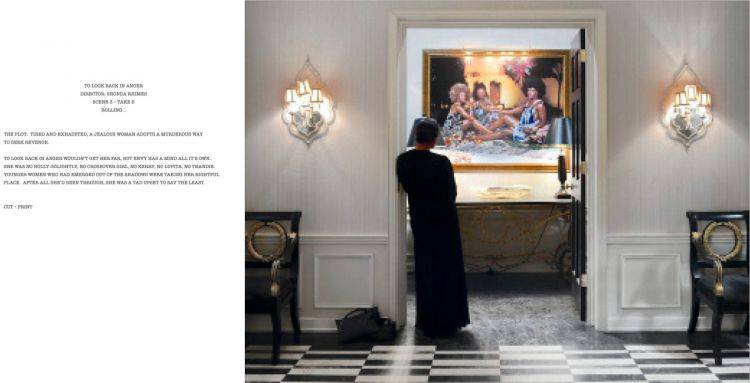

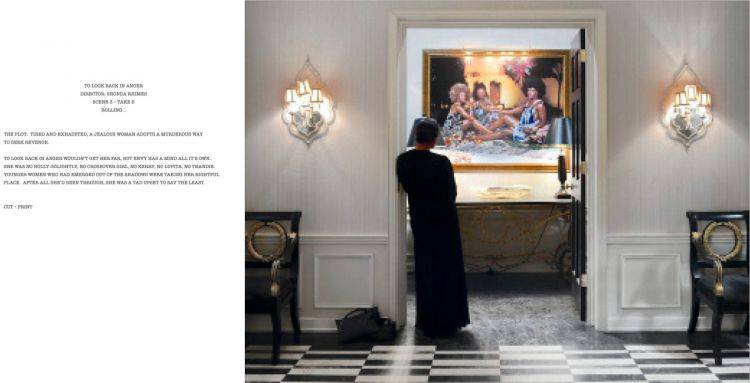

In a third series, Scenes & Takes, Weems reprises her black-robed muse persona to take self-portraits at various film and television sets. Despite the recent successes of Viola Davis and Shonda Rimes, she wants to remind us, the presence of a black women in entertainment is still anomalous, indeed unsettling.