Through January 14, 2024, the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation is showing Men Untitled, by Carolyn Drake, the winner of the 2021 HCB Prize. Drake’s work is first and foremost the fruit of anger – a dull anger towards the man she didn’t know how to say no to when she was a teenager, sunbathing alone on the beach; towards the guy at university who called her a “whore” after abusing her while she was unconscious; toward her fear of walking alone in the streets of the United States. Beyond that, Drake is furious at the larger patriarchy, and this anger is an essential driving force in her artistic work. Drake explains, in the epilogue to the book, that an unresolved fear of looking at men led her to arrange portrait sessions in which she asked male subjects if they would agree to undress for her photographs. “This is something I wouldn’t have dared to do when I was younger,” she writes in the preface to the accompanying book Men Untitled (TBW Books, reviewed in this issue), “but at fifty, some men don’t really see you as a woman, and this fact fortifies my imagination.”

Drake, whose previous series, Knit Club, focused on a group of women in Mississippi, challenges conventional representations of nudity in the photographs on view here: her subjects are frail bodies marked by time, wrinkles, and sagging skin. In contrast to clichés of male virility, the subjects of her photographs are usually older, often overweight men whom she refuses to idealize. Her aim is to explore a masculinity in decline. She photographs the men slouched on a couch, wading through mud, or suspended by their feet in what appears to be a garage. One can’t help but feel sympathy for these vulnerable, sometimes ridiculous men. In both a literal and figurative sense, they are laid bare, and our perception of masculinity is challenged.

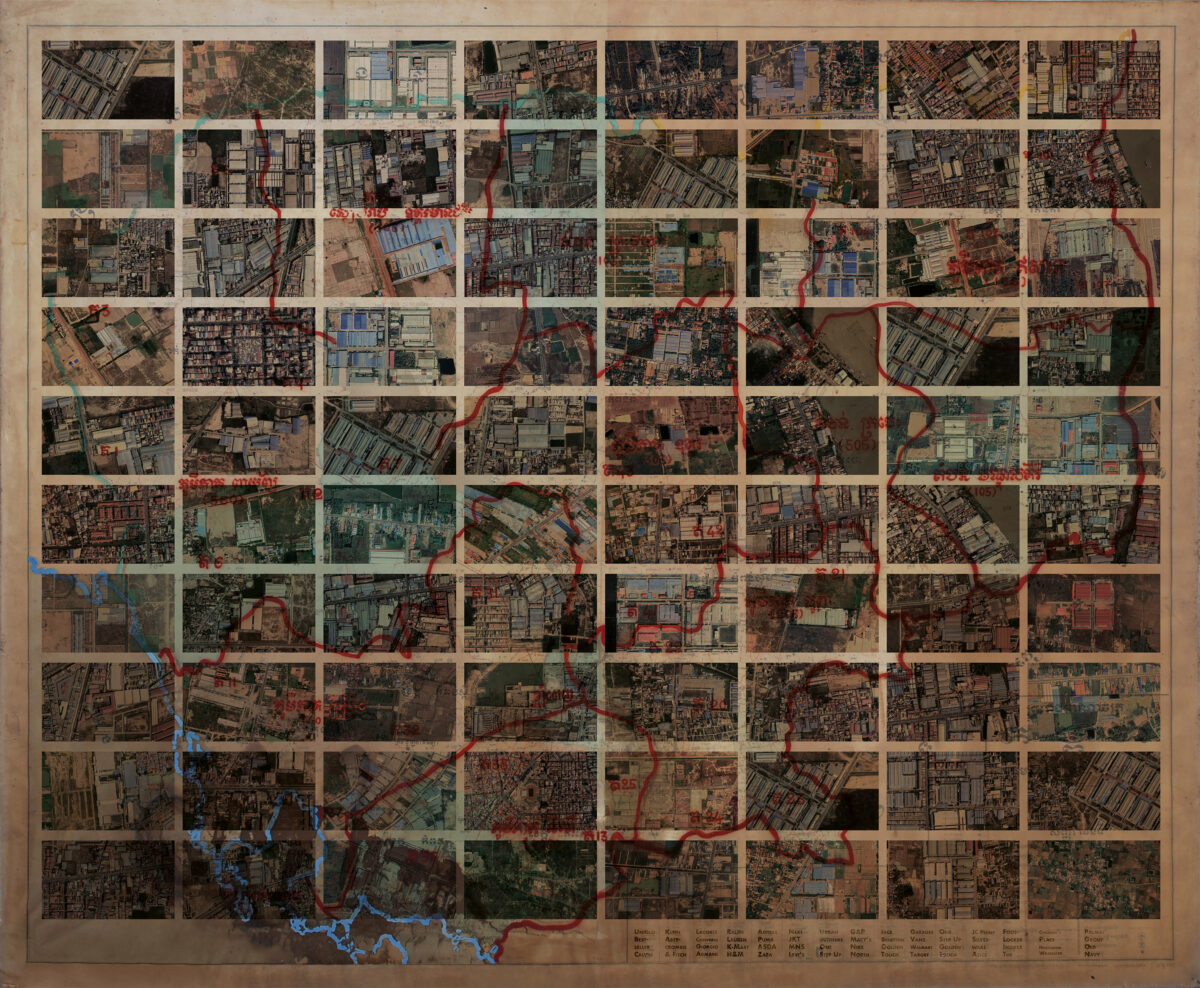

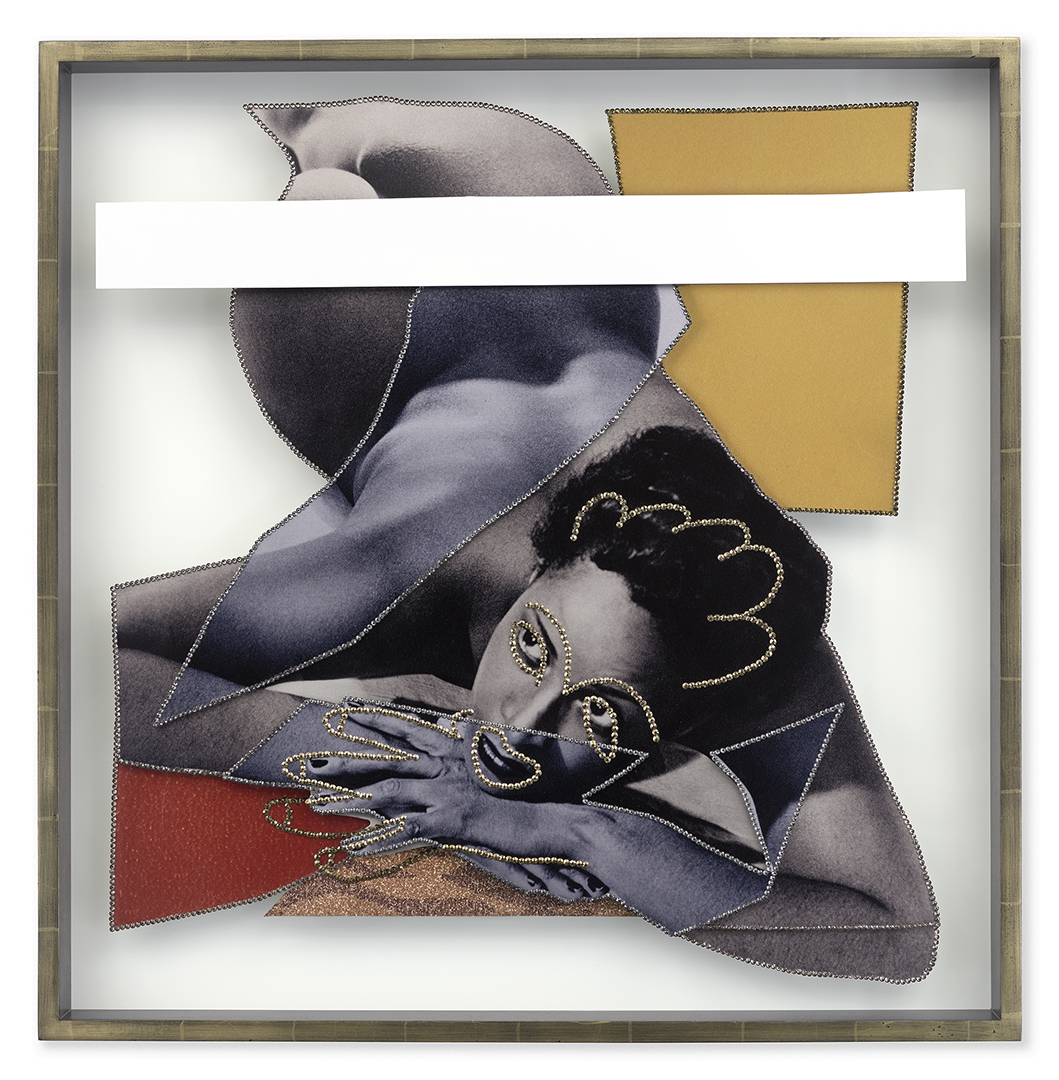

A smaller enclave in the exhibition space presents what Drake calls, in a video she recorded for the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, her “inner world.” The walls are covered with a “wallpaper of misogyny”: pages of the book Glorify Yourself, a beauty and seduction manual by Eleanor King that enjoyed great success in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s. The book’s idea was to encourage women to conform to beauty standards and stereotypical gender roles. The table of contents included items like Attractive Legs, A Graceful Walk, Sitting Technique, and Dieting for Size, and Drake photographed herself re-enacting poses from the book. More than a critique of patriarchy and the values of that era, this work is an act of introspection. What makes someone a man or a woman? This question is an underlying motif in Drake’s photographs, one brought to the fore in her self-portraits. Stripped of feminine signifiers, she blurs the boundaries of gender, questioning her own gender identity and observing in a text accompanying the exhibition that this work “dissects all these internal questions, adding, “My body is a tool of expression rather than a reflection of a fixed identity.”