The title of Bruce Davidson’s exhibition, Subject: Contact, was a double entendre. The show featured enlarged contact sheets from four series produced in the 1950s and ’60s – Circus, Brooklyn Gang, Time of Change, East 100th Street– that demonstrate Davidson’s method of getting to know his subjects up close and personal instead of shooting from the hip or on the sly, what today might be called embedded journalism.

In an exhibition that highlighted process as much as the photographer’s eye, enlarged images of Davidson’s contact sheets were shown alongside individual prints. The film strips are like the analogue version of the iPhone live photo feature that shows three seconds of action before the photo was taken. The inclusion of contact sheets also aligns with our Instagrammed lives and image-saturated world, where photo dumps require just a few taps of the finger and editing is optional. It’s also a clever way of recontextualizing familiar works.

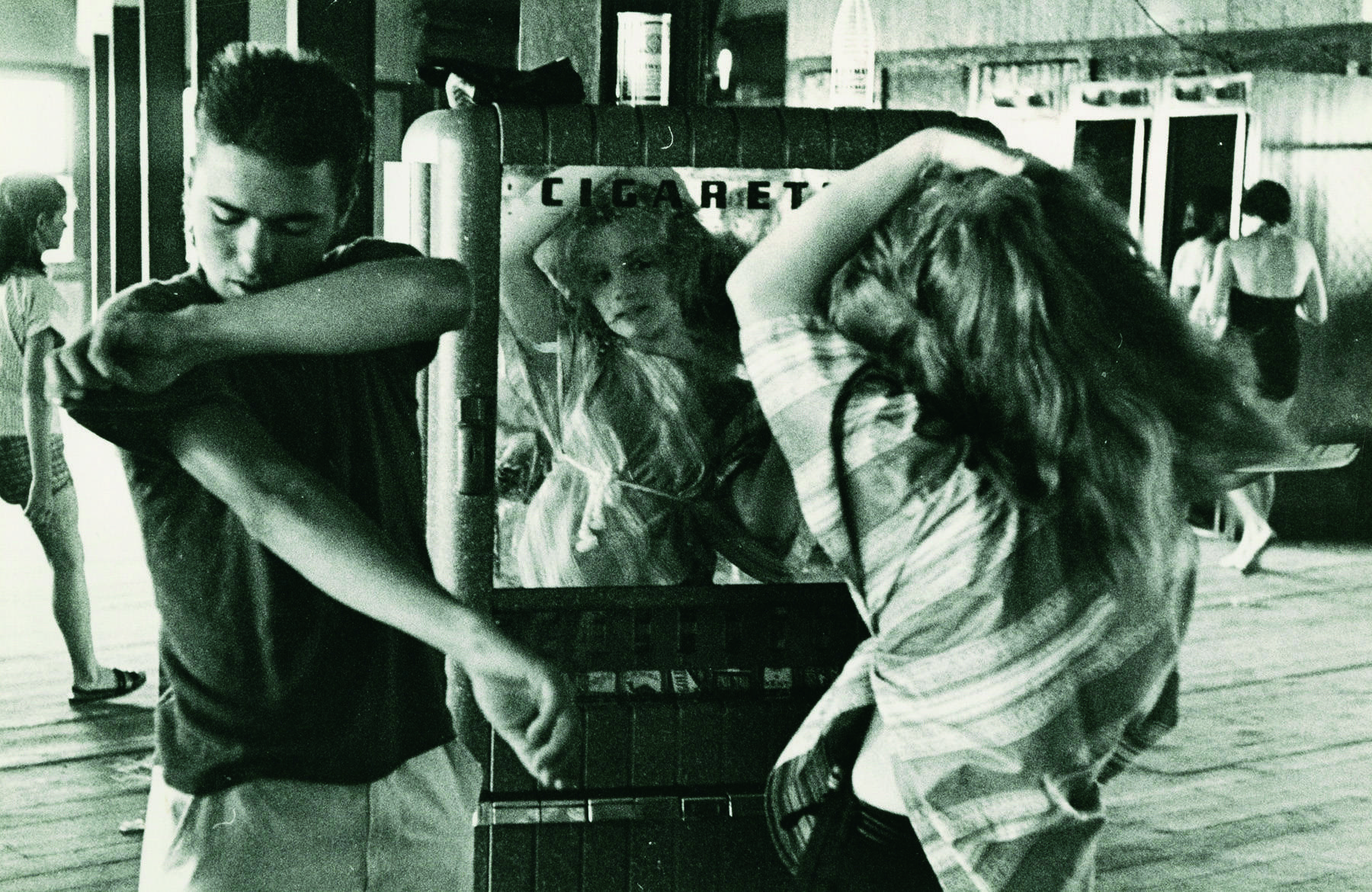

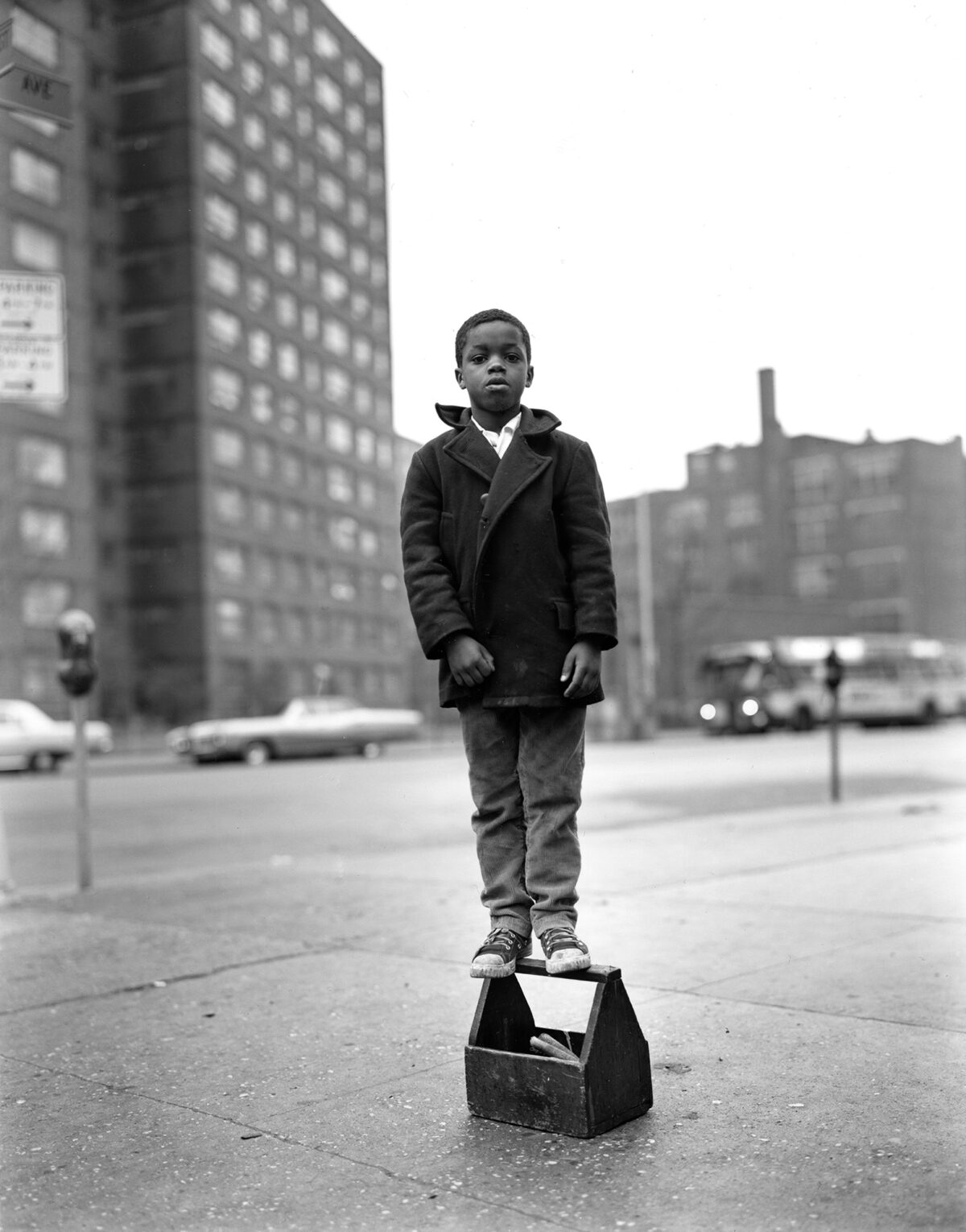

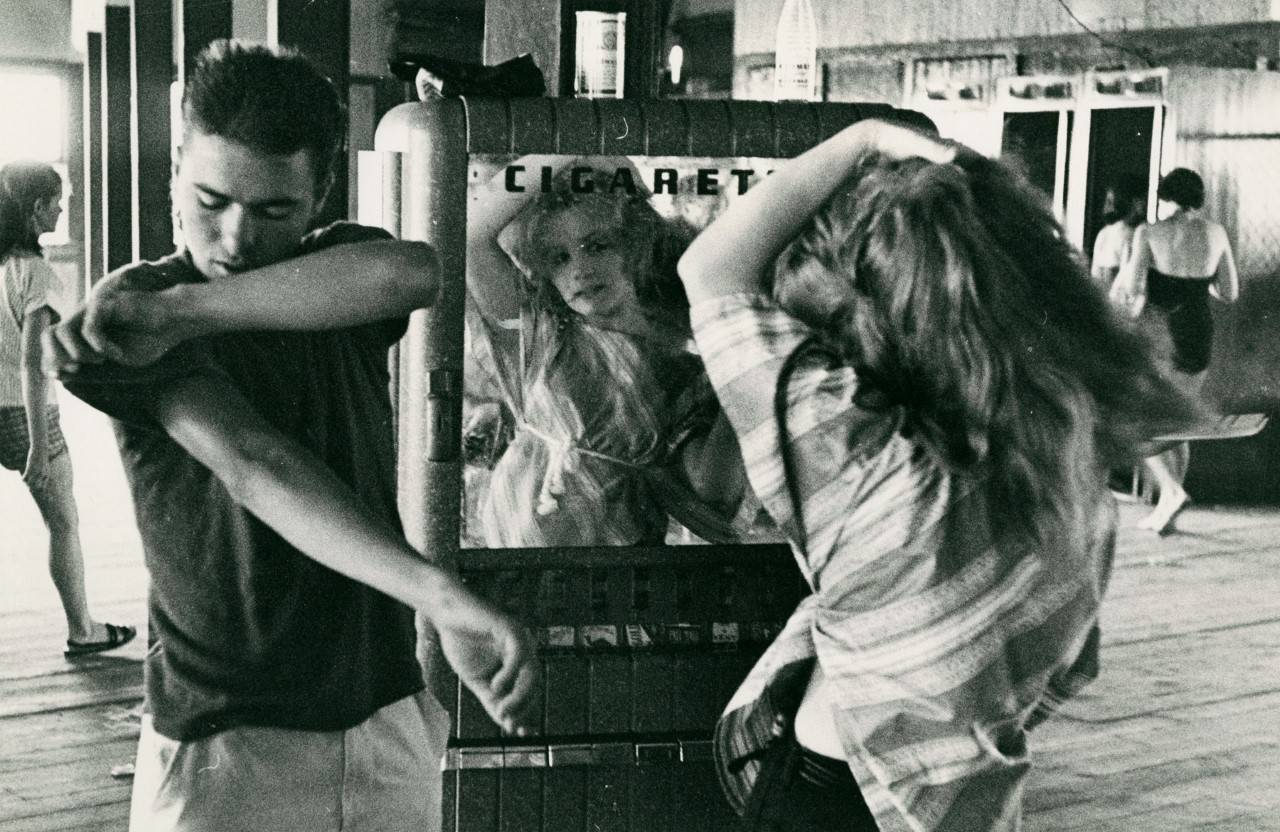

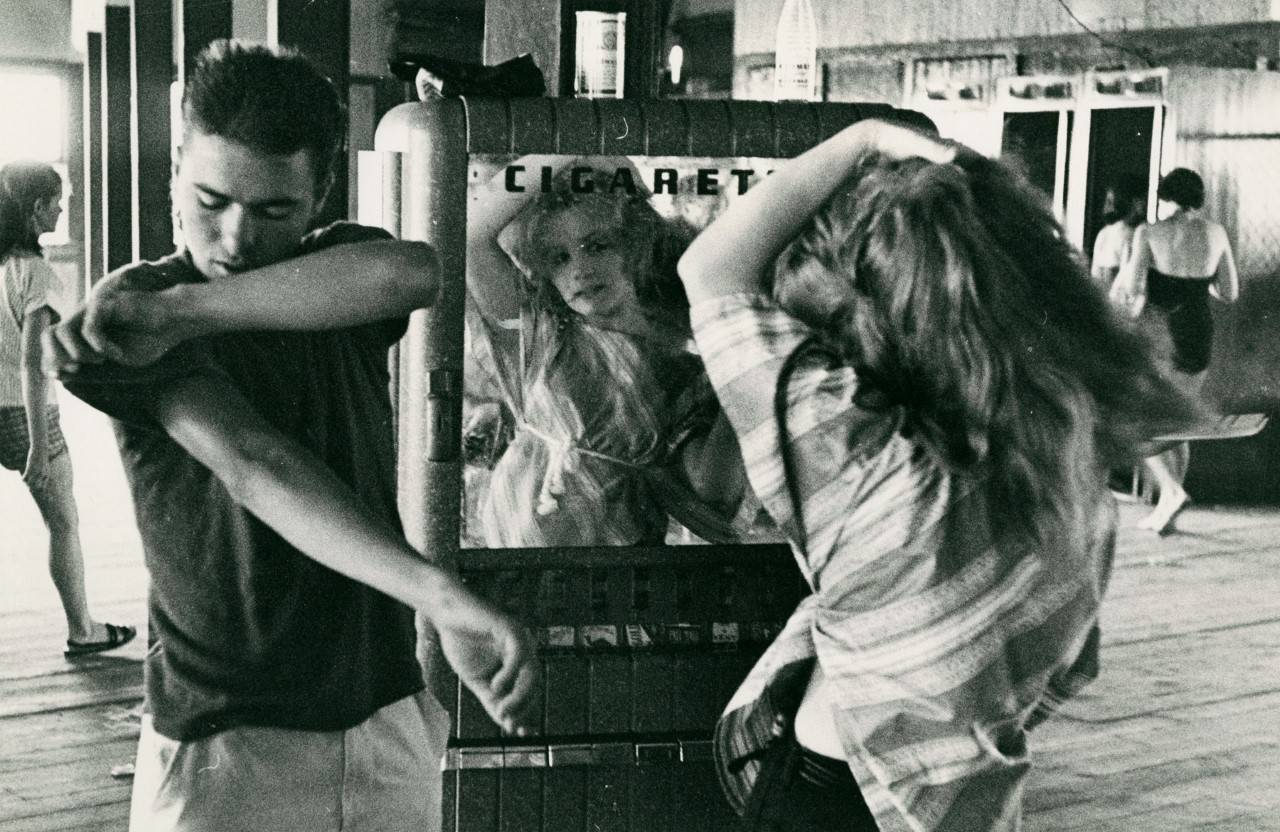

His series Brooklyn Gang might have shown this working method to best effect. In 1959, as stories of street-fighting were reported in the news, he hung out with a teen gang – at Coney Island, at parties, on the street, etc. – getting to know them as individuals. The candid photos suggest a certain intimacy, but it is in looking at the contact sheets that the teens’ ease with Davidson is most apparent. Similarly, in the East 100th Street series of 1966-68, the image of a scrawny girl in baggy underwear standing on a fire escape – in the contact sheet she also holds a rabbit – suggests a child’s comfort in a parent.

But it is Davidson’s Circus series featuring Jimmy Armstrong, “the dwarf,” that is perhaps the most compelling, if oppressive. Armstrong is seen in clown makeup, cigarette always in hand, in the gritty and forlorn backstage of a circus in Palisades, New Jersey. We see him, for example, in a cramped bunk in a trailer, smoking, standing outside a tent with two elephant asses looming over him, smoking. The images evoke a feeling of loneliness and ostracization, as when a group of gawking schoolchildren surround Armstrong, who appears all too familiar with the scrutiny.

While Davidson’s photos indulge in the troubling notion that poverty is picturesque (a trope perpetuated by many artists with less humanistic intentions), they were groundbreaking in a time when society was complacent about glossing over realities that conflicted with belief in the American Dream. Along with works from Time of Change, Davidson’s photos of the Freedom Riders and the Civil Rights era, the exhibition reminds us that though the faces have changed, the circumstances remain the same.