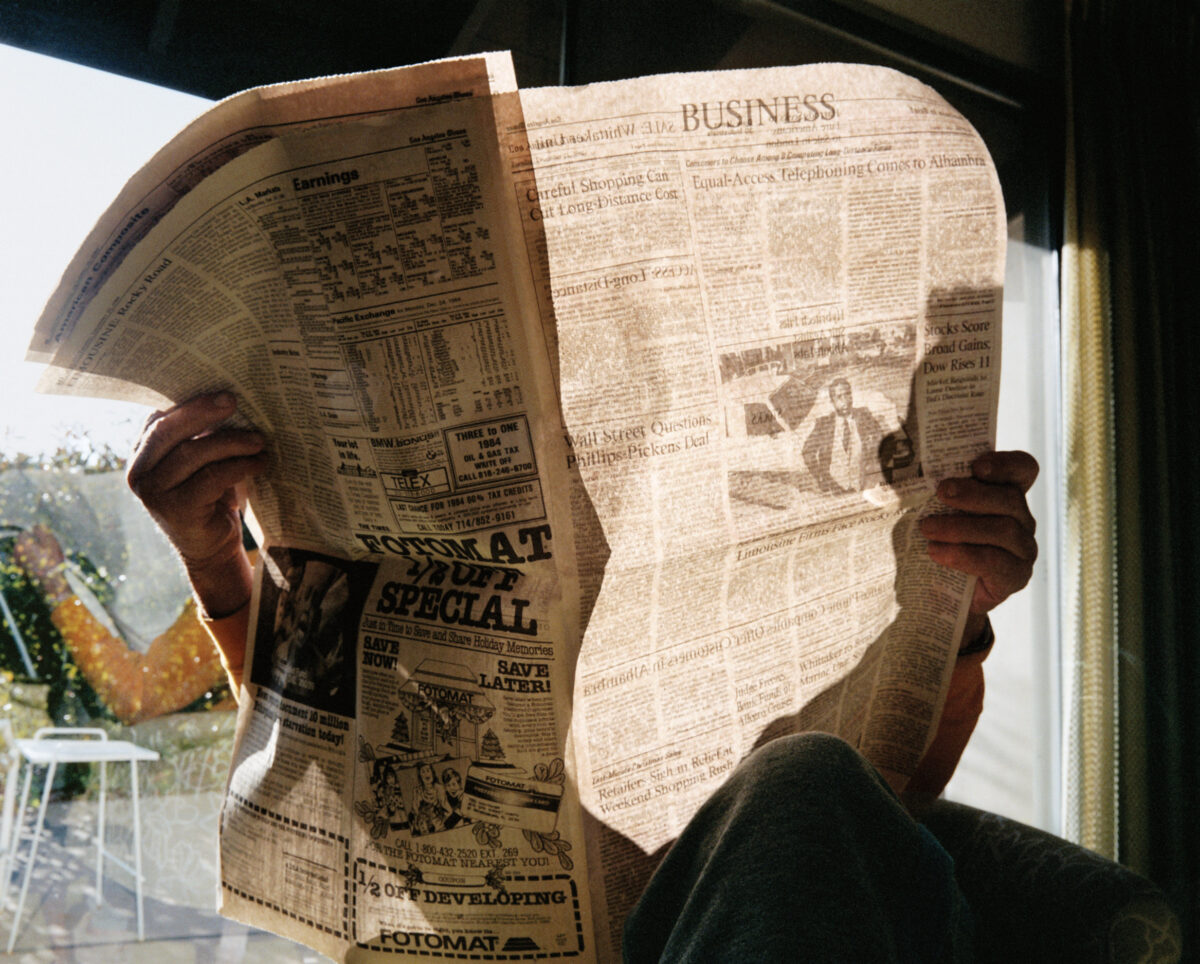

A self-taught photographer under the Soviet regime in Ukraine, Boris Mikhailov has been making experimental photographic work about social and political subjects for more than 50 years, dismantling propaganda with a sharp undercurrent of sarcasm. Before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, his studio was regularly searched by the KGB, who suspected him of being a spy, and his images were censored by the regime because they were considered subversive. Those pictures, however, made him one of the most influential contemporary artists in Eastern Europe. Ukrainian Newspaper, on view at MEP through January 15, 2023, is the largest and most exhaustive retrospective of the photographer’s work to date.

Conceived in close collaboration with the artist, Ukrainian Newspaper brings together more than 800 works and showcases 20 of his most important series. Tea, Coffee, Cappuccino (2000-10) paints a grim but frank portrait of his native city, Kharkiv, documenting the pervasive influence of western capitalism, in contrast to the country’s permanent poverty. Huge advertising banners and colorful billboards populate the city, while old women offer “tea, coffee, cappuccino” to pedestrians. The photographer turns his lens towards the less well off, sitting with their shopping bags, waiting for the streetcar.

Mikhailov’s early work is represented by Red Series (1968-75), which opens the exhibition and reveals the omnipresence of the Soviet military in Ukraine. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the red flags, placards, and billboards that had filled the streets disappeared almost instantly. In Mikhailov’s images, red was replaced with a cobalt blue that evokes cold and hunger. In the horizontal, hand-tinted images in At Dusk (1993), people queue for food or huddle around a bonfire. The social criticism in other images is implied rather that stated outright: The photographs in Yesterday’s Sandwich (1960s-1970s) allude to coded messages, common in times of artistic restrictions. With a biting but poetic irony, Mikhailov creates absurd and disembodied montages, including a giant pig purse wandering the road, or an armless Christ lying on two fried eggs.

Mikhailov’s work explores the boundaries between documentary photography, conceptual work, painting, and performance, incorporating unexpected angles, photo montages, superimposed images, and colorization. In Luriki (1971-85), he hand-painted anonymous family photographs. But this colorful world is fake, illustrating how the Soviet regime tried to embellish the image of people’s daily lives through propaganda. Often blurred and crudely printed on cheap paper, Mikhailov’s images are imperfect and flawed, like life.

With his wife Vita, Mikhailov invited homeless people into their house and asked them to pose for a sum of money. Anamnesis (1997-98) fill an entire room, a series dedicated to the paupers, the ostracized, the vagrants, and the alcoholics, a gallery of tragic characters.

Above all, Mikhailov’s work reflects the upheavals that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet Union and its aftermath and mirrors a time that was a precursor to the present war. His sometimes violent, sometimes disturbing images have created a dialogue with history and memory.