Bill Brandt embraced ambiguity, in his life and in his art, and the thoughtful, well-organized exhibition on view at The Museum of Modern Art through August 12 emphasizes his refusal to be pinned down to a particular style or subject. The German native who became known as the quintessential British photographer was also a documentarian who evolved into a surrealist.

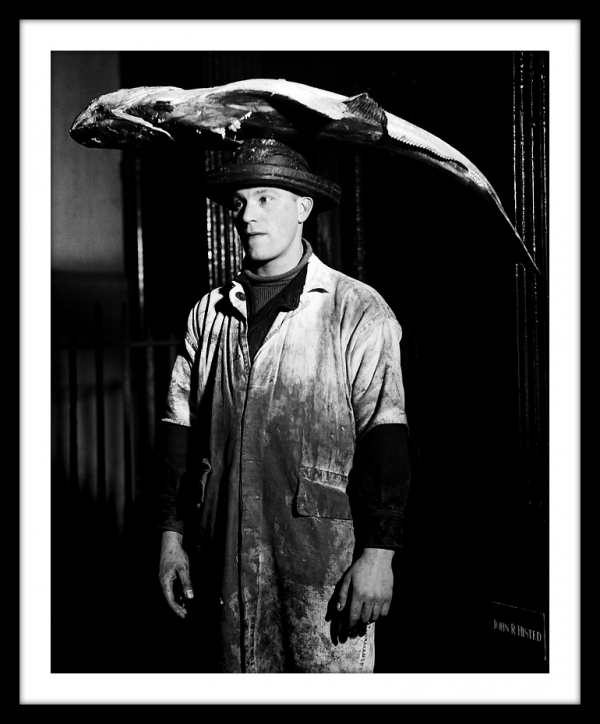

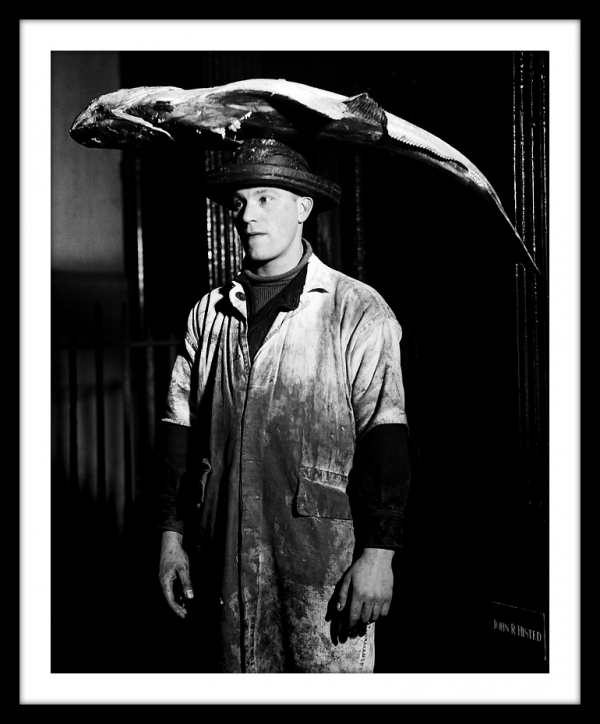

Brandt made his name with his extensive, almost ethnographic study of English society, The English at Home, in 1936. Though he adopted England and encouraged the misperception that he was a native, the fact that he wasn’t may have positioned him to photograph the class stratifications of British society with such equanimity. His gaze was the same whether it was focused on a fishmonger at Billingsgate Market or the upper classes at their leisure, playing golf or watching cricket. Brandt had family connections that allowed him access to some of London’s affluent families, and he regularly photographed his uncle’s maid, Pratt. Parlourmaid and Under-Parlourmaid Ready to Serve Dinner emphasizes the crisp white uniforms, but also the women wearing the uniforms, pulling them forward from the background into the foreground and focus of his pictures.

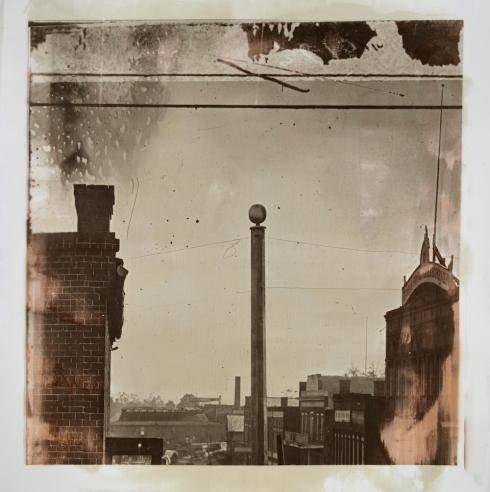

The coal towns of northern England seem tailor-made for Brandt, drawn as he was to greys and blacks in his brooding early prints. In the late 1930s he traveled to places like Halifax and Jarrow, and you can feel the soot in your lungs in Halifax, in which a dark cloud of smoke wafts over the street. But there are also hints of the disorienting perspectives that would predominate in his later work: In A Snicket in Halifax, 1937, a wet, cobblestone lane looms up dizzyingly and seems to end in mid-air. And his photograph of three eggs in a gull’s nest on the Isle of Sky, 1947, has a surreal quality that may be the result of the time Brandt spent as an informal apprentice to Man Ray in Paris before moving to London in 1934.

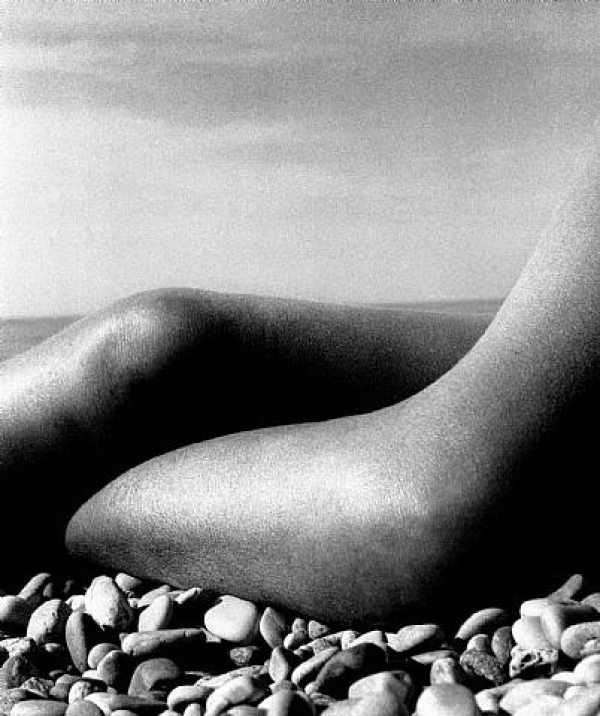

Man Ray’s nudes certainly influenced Brandt, who eventually turned his attention to the subject. These strange and unpredictable images may be the work for which he is best known, and as curator Sarah Meister points out in the catalogue for the show, they are made even more compelling by their elusiveness. They are sometimes so distorted that it’s difficult to make out a body part, and that part might just as easily be a foot or an ear as a breast, the setting as often a bed as a rocky beach.

Just as he experimented with distortion and framing, Brandt continually experimented with printing (even going back and making high contrast prints of earlier shadow images). Three versions of London (1953, 1969, and 1970s), a geometric composition showing a woman’s oval face through the crook of her arm, her breast in the lower corner, are on view in the show. He printed the image in increasingly brighter whites and deeper darks, sharper and higher in contrast, resulting in subtle changes to the tone and mood of the picture. Brandt wrote that the photographer’s job was to enable “men and women to see the world anew” as something “fresh and strange.” It’s clear from this exhibition that he, for one, never stopped seeing the world that way.