As the first artist-in-residence at the New-York Historical Society, German-born, London-based artist Bettina von Zwehl was asked to create a project in response to works in the NYHS collection. During her stay in the city, the Parkland, Florida, school shooting happened on February 14, 2018, followed by a student “die-in” five days later in front of the White House to protest gun violence. Calling for tighter gun-control laws, the protesting students presented themselves as potential future victims.

The works comprising Meditations in an Emergency, on view through April 28, are a logical extension of von Zwehl’s usual practice, which largely consists of side-facing portraits and silhouettes. She was drawn to the museum’s collection of American portrait miniatures, and in particular the 18th- and 19th-century profile drawings by Benjamin Tappan. For her project, von Zwehl conflated an historical art form – cut-paper silhouettes – with history in the making.

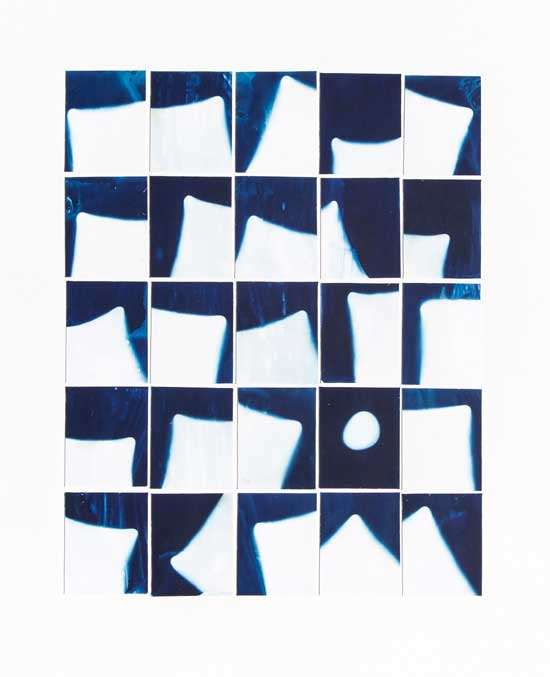

To create her photos, she recruited teenagers from New York City schools to pose for photographic silhouettes that she describes as “death masks sculpted from life.” The installation is appropriately funereal. Seventeen photographs – one for each of the victims in Parkland – line three walls of a somber, dimly lit gallery. The images are repetitive: all of the students were photographed lying on their backs, oriented in the same direction, with eyes closed. The effect is chilling; their supine position is intended to reference the student die-ins, which themselves are intended to resemble a lot of dead kids.

Together, the images make the students nameless and faceless, a sort of collective, symbolic victim. But that is arguably the problematic outcome of so much news coverage about multiple mass shootings. We’re losing the sense of individual tragedy; the events are blurring together.

In viewing the individual works, details emerge that hint at the students’ personal styles and, perhaps, personalities – a girl’s delicate necklace, a boy’s spiked hair, another boy’s messy locks under a knit hat. These subtle details serve as reminders of each teen’s humanity, and of a life cut short. The tragedy of von Zwehl’s show, and by extension society today, is that young victims of senseless mass murders are now an archetype.