The exhibition spanning the career of Los Angeles photographer Anthony Hernandez at the San Francisco Museum of Modern last year (and currently on view in Milwaukee) showed clearly that Hernandez, now 70, is a pivotal figure bridging the tradition of street photography and later developments, often grouped together under the New Topographics rubric. For the artist’s first solo show at her gallery (on view through October 21), Yancey Richardson showed works from two of the Hernandez’s most critically acclaimed series: Public Transit Areas (1979-1980) and Landscapes for the Homeless (1988-1990).

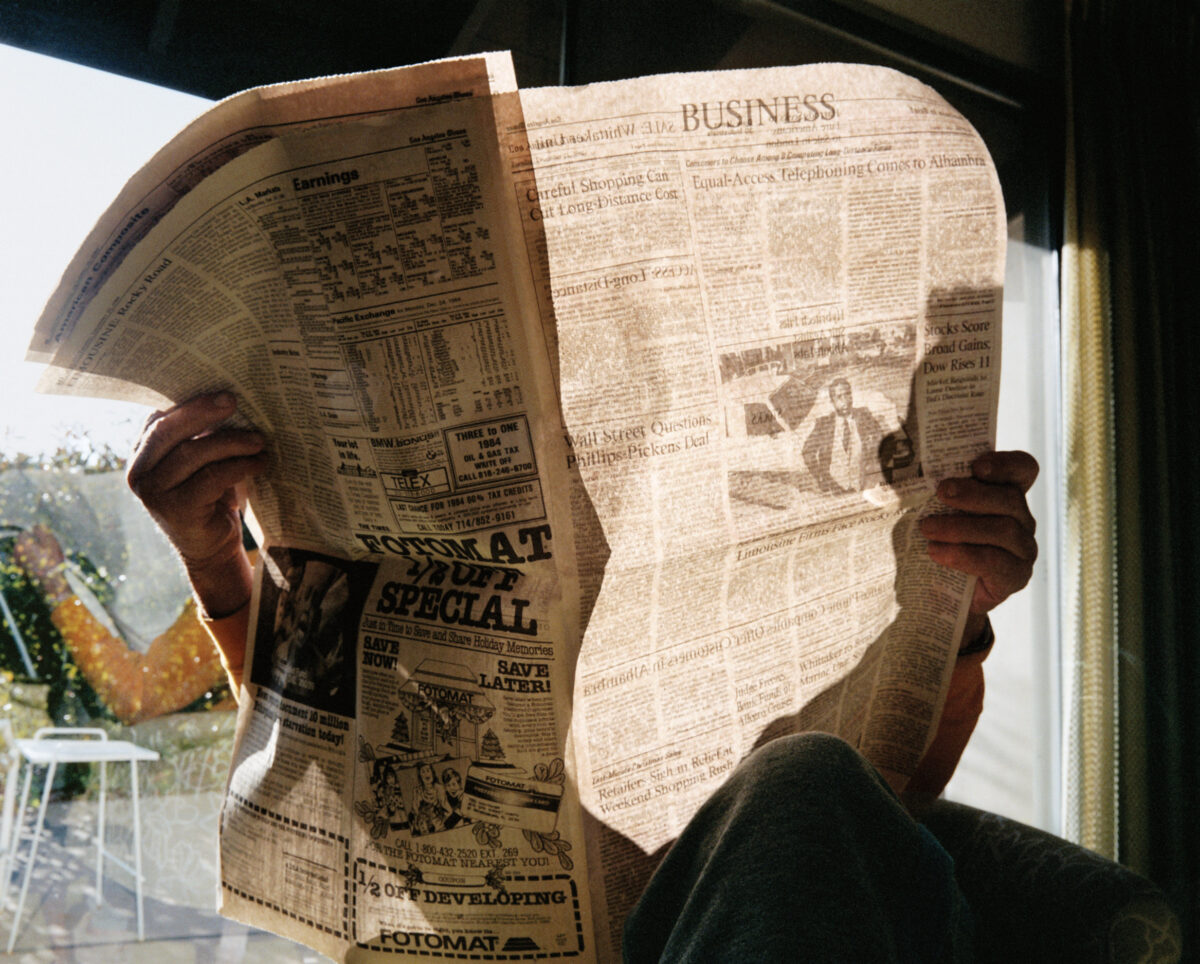

Hernandez’s early work was executed in a highly refined “social landscape” aesthetic and was shot with 35mm. Yet, this work was suffused with the particular psycho-geography of his native city. L.A. is dominated by cars, and bus stops are nearly invisible sites that have always been used almost entirely by working people of color. For Public Transit Areas, Hernandez swapped his 35mm for a large-format, 5 x 7 tripod-mounted Deardorff view camera. While earlier street photography – Winogrand and William Klein in particular – emphasized the fast-paced, manic energy of urban life, these pictures display an austere, almost classical order: dramatic one-point perspective is heightened by sharply receding diagonals, with verticals rising up along their sides. Since the larger format creates such a uniformly sharp depth of field, the human subjects command no more of our attention than, say, a signpost or bench, which only serves to magnify the sense of brooding alienation.

Hernandez is most often associated with the New Topographics photographers Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz. He shares with them a careful attention to visual structure and a consistent, almost minimalist approach to composition. In Landscapes for the Homeless (1988-1990), he continues in this vein. Setting out on foot, Hernandez documented – under freeways, in vacant lots, and in other abandoned and neglected locales – the resting places, campsites, and improvised dwellings of L.A.’s then-burgeoning homeless population. We are placed, front and center, in their “homes.” The human presence is registered as absence by the evidence left behind: a chair fashioned from scraps of plasterboard; oversize trousers splayed across tree branches; a yellow “curtain” stretched across low vines. As in Public Transit Areas, a continued blurring of the lines between elegant formalism and social critique calls attention to certain realities of life in L.A. from which most choose to avert their eyes, while at the same time avoiding the easy cliches of humanist documentary.