An exhibition such as A Long Arc: Photography and the American South Since 1845 invites criticism. Sweeping exhibitions about the complicated region are hardly unusual – the traveling exhibition Southbound was not so long ago – and even the most well-meaning survey can fall into romanticization or exploitation by reducing the very subjects it wishes to uplift into caricatures and stereotypes. A Long Arc deftly sidesteps this trap by taking the focus off Southern identity (impossible in any case, since a singular identity does not exist) or attempting to tell a narrative (whose, and with what authority?) and instead puts the focus on photography itself.

From its entry point in the years leading up to and during the Civil War, the exhibition focuses on photography’s relationship to the South throughout history, and how the medium has been used to push and pull the South’s gooey identity across time. Or rather, it is less about the identity of the South and those who live there, and more about how the region is seen.

The American South is often the center of crisis and disaster, a political and social hotbed, and a site of economic deprivation. In other words, a veritable flare gun for photographers. The Civil War, Reconstruction, the Great Depression, the Civil Rights Movement, and more recently, environmental calamity have all brought photographers to the region. A Long Arc takes the viewer through time, beginning with slavery and the Civil War, during which the photograph was used to document, but also as a propaganda tool on both sides. Half-plate daguerreotypes and albumen silver prints, some faded with signs of decay, present portraits of enslaved people, free Black Americans, and slaveowners. Some images were taken to depict the horrors of slavery and circulated in support of abolition; others attempted to cover up the truth of such horrors by presenting an “idyllic” antebellum economy. In the Civil War photographs on display, which are some of the earliest examples of combat photography, we begin to see a trend that continues to this day: the use of the Southern landscape as a metaphor for trauma. George N. Barnard’s Ruins in Charleston, S.C. (1866) shows crumbling buildings as evidence of the devastation of war, but also employs dramatic lighting and scale to enhance the connection between the ravaged landscape and the two small figures surveying their surroundings.

The exhibition proceeds chronologically with an extensive display of works from Reconstruction and the Great Depression, and then the High’s impressive collection of Civil Rights photography. Iconic and instantly recognizable images by Gordon Parks, Doris Derby, Robert Frank, and many more emphasize the South’s legacy as ground zero for the fight against injustice.

Atlanta, as a city, cultural hub, and historical site, takes a front seat in A Long Arc, particularly in the works from 1970 to the present. Atlantans may be intrigued to find their neighborhoods represented – in Oraien Catledge’s images of Cabbagetown residents from the 1980s, for instance, or Joel Sternfeld’s Domestic workers waiting for the bus, Atlanta, Georgia, April 1983, which shows racial and economic inequalities in the wealthy suburb of Sandy Springs that continue to reverberate today.

The exhibition’s framing – roughly the history of photography through images of the South – shifts slightly in the vibrant final section displaying contemporary artists who grapple with questions of identity and current political climates more overtly. While previous photographic eras are perhaps more easily defined in 20/20 hindsight, our current time, as evidenced by the contemporary works on display, has exploded any definitions of what Southern photography is or could be.

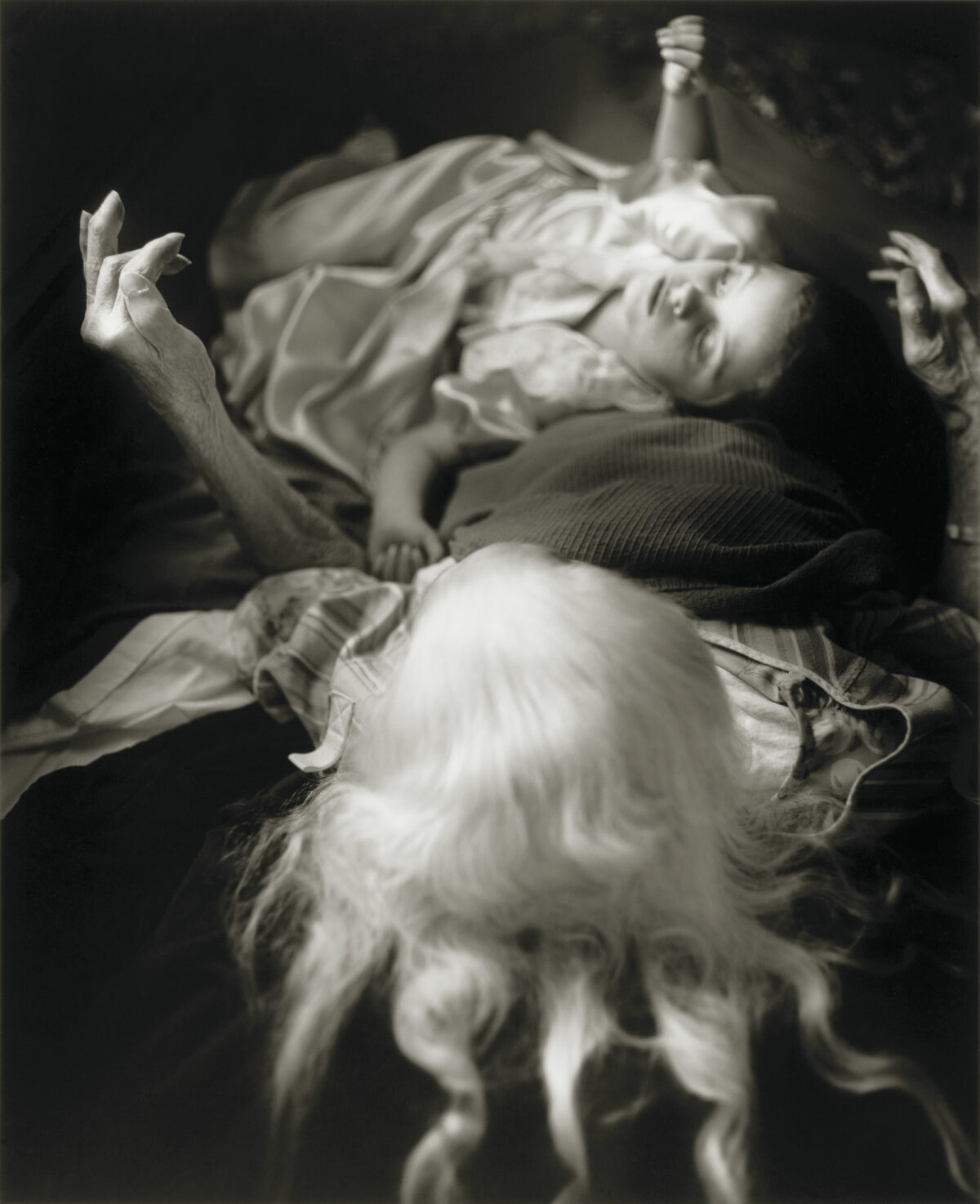

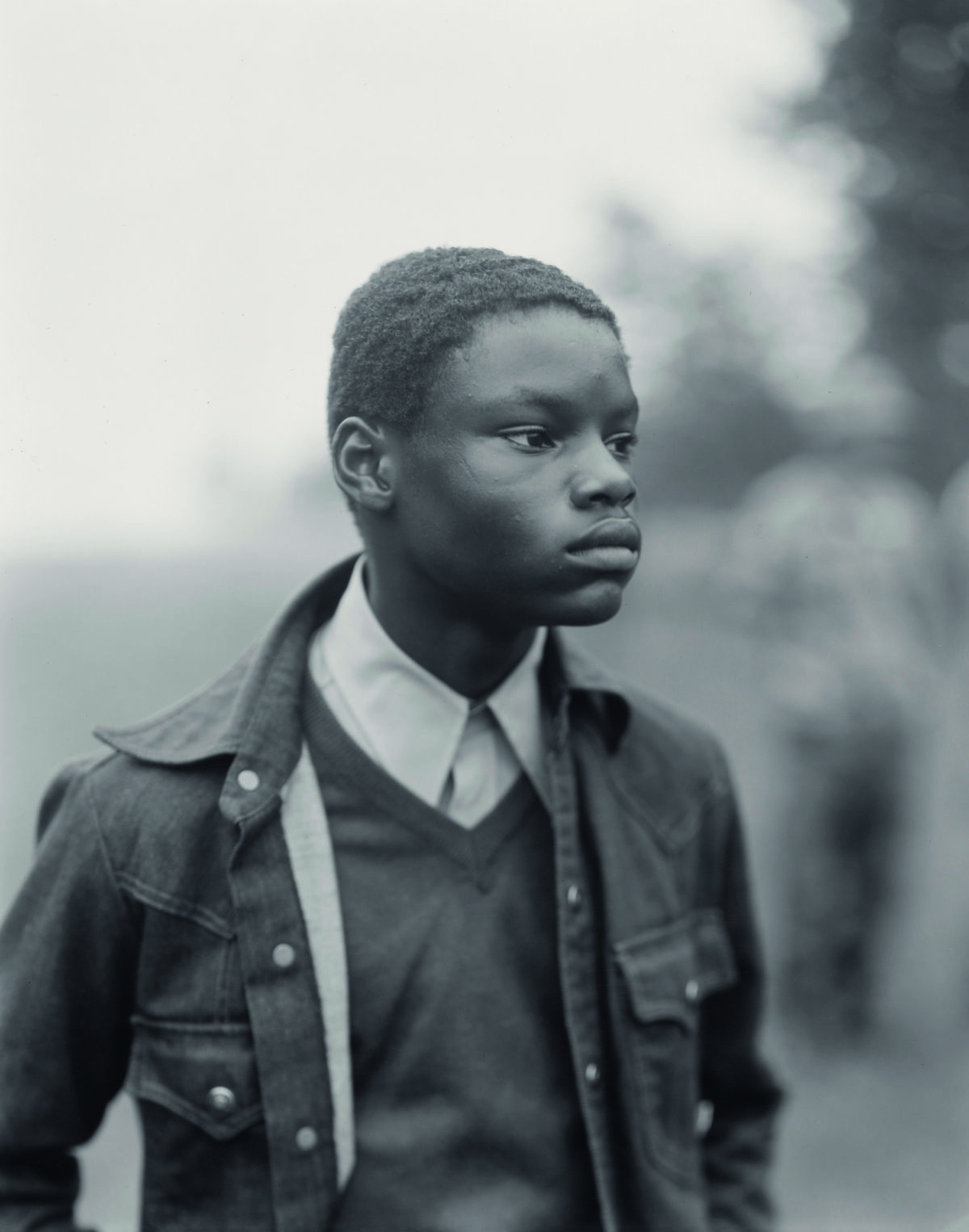

RaMell Ross speaks to such complexities, using the iPhone to play with notions of what it means to capture history, and who gets to tell stories. In iHome (2013), an antebellum house, a signifier of white Southern wealth, is shown in-focus on an iPhone screen held by a Black hand in the foreground while also shown blurred in the background, suggesting that new perspectives can offer clarity to previously warped narratives. Curran Hatleberg’s Untitled (Hole) (2016), like many of the photographs displayed in earlier eras, looks at labor, but elevates it to epic proportions as a small group of workers observe a mysterious grave-like hole in a junkyard, Kudzu-covered trees towering above them. There are striking photographs that point toward the cost of environmental degradation in the South – instead of landscape as metaphor, landscape as a horseman of doom. Other images, such as Sheila Pree Bright’s Untitled 28 (2007) from the Suburbia series, seeks to upend stereotypical narratives of Black communities by turning the lens on Black-owned homes and interiors. In this final section, we also see – arguably for the first time in the exhibition – a wider, more inclusive representation of the South. José Ibarra Rizo’s work Limbeth and Karim (2021), from the series Somewhere In Between, emphasizes care and intimacy between a young couple to counteract reductive narratives about Latinx communities, and Peyton Fulford’s Rian With Friends (2017), which depicts a group of young people entangled together on the grass, uses touch and softness to depict queer circles in the South.

Across the eras, there are recurring subjects: diversity, poverty, oppression, activism, labor; and recurring themes: landscape as stand-in for psychological trauma, labor as signifier of oppression or freedom (depending on the photographer), and the Southerner as “other.” There is an ongoing emphasis, perhaps even obsession, with portraiture. But for all the South’s publicly perceived infatuation with tradition, and for all the photographers who sought to capture the region for an array of personal and political reasons, the collection of photographs in A Long Arc point most forcefully to a region of roiling and constant change.