The photographs in Janelle Lynch’s series Another Way of Looking at Love felt, the first time I saw them, like a balm. We’d scheduled a studio visit for November 9, 2016, blithely assuming the election the night before would end otherwise. Even the weather in New York – heavy, overcast, and grey – felt like doom. But Lynch’s photographs, taken on her wooded property in the Catskills in upstate New York, reminded me to breathe. Carefully chosen details – spiky, tangled branches, sun-dappled leaves in golds and greens, bright snaps of red – suggested a well-known and well-loved landscape, and the photographs brought me back to the pleasures and deep satisfactions of art, nature, and connection.

Since that studio visit, Lynch has published a beautifully designed accordion-fold book of the work with Radius Books (2018), and a selection of her photographs is on view through February 16 at the Hudson River Museum. She was also shortlisted for the Prix Pictet, whose theme this year is Hope.

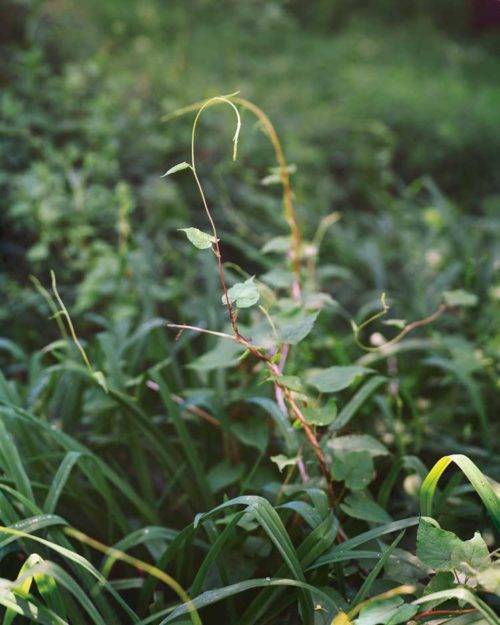

The book’s accordion-fold design refers, obliquely but effectively, to the bellows on the 8×10-inch view camera that she uses to make these photographs, which capture seasonal shifts: crisp reddish-brown autumn leaves; spare, Harry Callahan-like mark made by bare twigs against the snow; and images like Spring Tendrils, 2016, in which she’s pulled into focus a single, delicate, shoot shyly unfurling itself, while the surrounding greenery fades into the background.

Lynch began the series in 2015, following a period in which she studied painting and drawing intensively at the New York Studio School. That practice encouraged a different sort of looking – what she calls a “heightened visual perception” – and that quality of attention is tangible in the pictures. Although she draws inspiration from painting, drawing, and literature (Wendell Berry and Mary Oliver are favorites) as much as from photography, her images are rooted in the precision of her photographic process. Her large-format view camera enables her to play with the depth of field in a way that pulls shapes and patterns into the foreground. Her pictures establish what she calls a “suggestive space, open to interpretation, and to imagination.” The branches in Summer Wreath, 2016, bend toward each other to create an aperture-like opening, a circular shape that recurs in other photographs in the series. The branches are not actually touching, though they appear to in her photograph. It’s a hopeful bit of deception, the idea that if we alter our way of looking, or shift our vantage point, we’ll find connection. What better reason to engage with art in troubled times? As Michael Chabon put it in a recent essay for the Paris Review, “We are only one poem, one painting, one song away from another mind, another heart.”