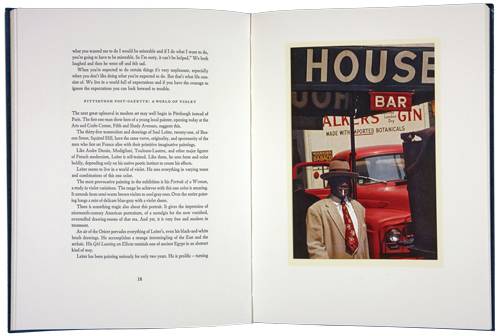

Harf Zimmerman was born in Dresden after World War II and grew up in the divided Berlin of East Germany. Dresden was almost completely destroyed by bombing and the urban landscape of East Berlin consisted mainly of large gaps between buildings that the bombs had missed – blocks of empty rubble-strewn lots, lined by so-called “firewalls.” Originally hidden from sight within the structure of the buildings, the firewalls were protective walls between two buildings, sturdy enough to remain standing. When Zimmerman took his first picture of one of the still-visible naked walls in 1988, something resonated for him. But it took until 1996 for him to understand what it represented for him, at which point he embarked on his Firewall project, which engaged him off and on for the next 20 years.

It seems obvious that where and when Zimmerman grew up shaped him as a person as well as a photographer. The spark he experienced in 1988 eventually grew into an artistic document that encompassed far more than his individual emotional landscape. The firewalls left standing were seductive objects for Zimmerman to explore with his large-format camera, but more importantly, their fading surfaces became testimonials to Germany’s past. These photographs were published in 2015 by Steidl in the book BRAND WAND.

While in the West, cities were re-built and walls were re-plastered, in the East, they became open-air museums of preserved World War II wounds. After the unification of East and West Berlin, commercial developments created new buildings and the firewalls started disappearing. Zimmerman captured a piece of history slowly vanishing. The firewalls he photographed preserved a specific time in East Germany – from pre-war jolly advertisements to post-Unification graffiti, and much in between.

His photographs can be beautiful and lyrical, or melancholic and gloomy. They evoke the German’s love of romanticism and also the dark side of their history. Some bear witness to the horrors of war, others reflect Germany’s love of beauty and order. All of them are visually expressive. It speaks to the photographer’s artistic powers, and perhaps the depth of his emotions, that he turned these utilitarian constructions into a mirror on the German soul and the terrible consequences of war.