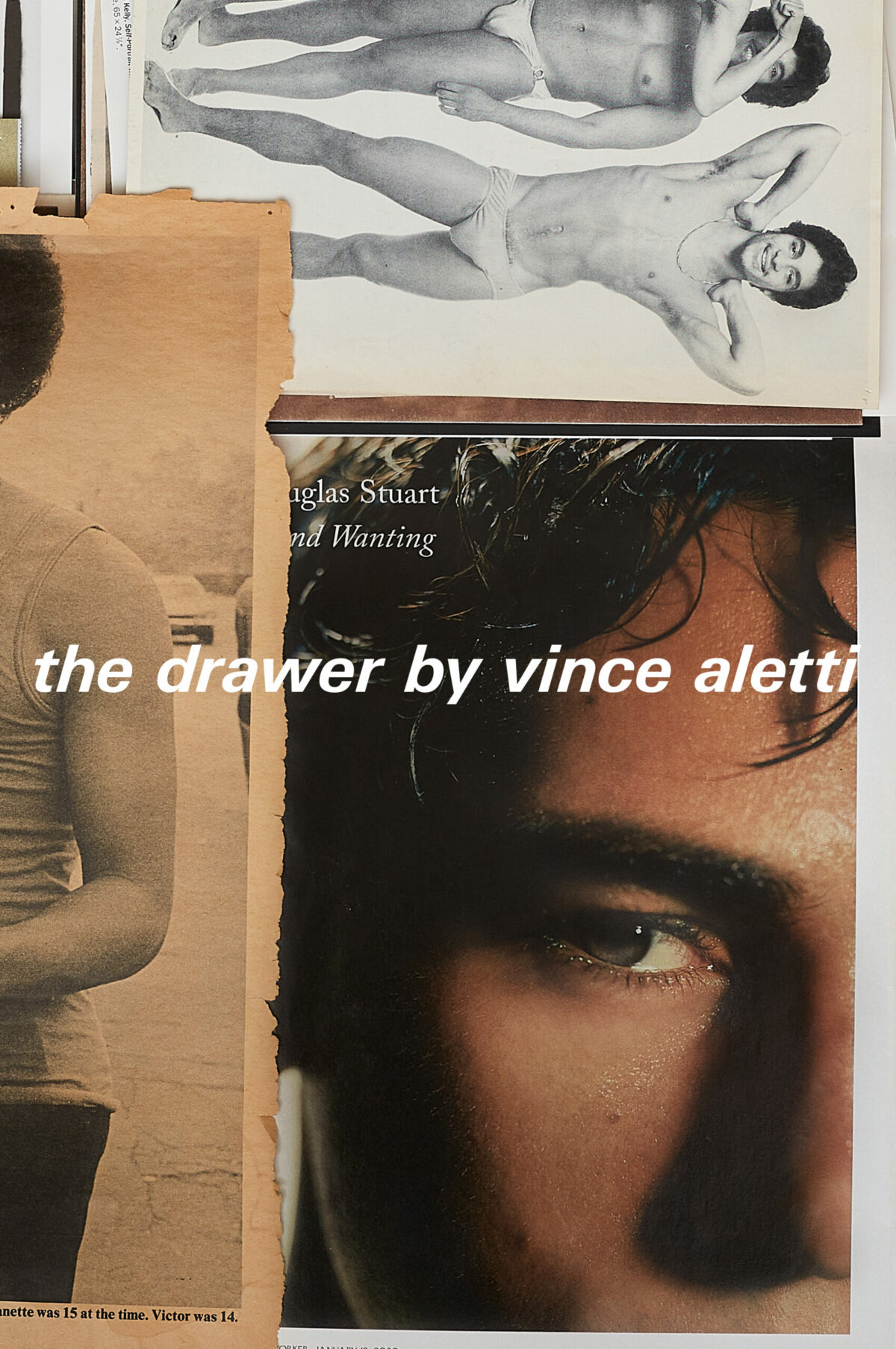

The publications Ari Marcopoulos collects in Zines (Aperture) were made between 2015 and 2021, years before and in the midst of New York’s pandemic lockdown. They’re typical of the small, Xerox-style pamphlets he’s been making for some years now alongside his gallery practice and more painstakingly produced bound books: casual, random, personal, immediate. Part wish-you-were-here update, part data dump. In 2012, he contracted with New York’s Dashwood Books to make a zine a week and turned out 52 issues collectively titled Anyway. “That nearly drove me insane,” he tells curator Hamza Walker in a rambling conversation dropped into the book. But the zines he produced during the pandemic were another matter entirely: “I had to make them to stay sane,” he says. They were a way to keep his lines of communication open and buzzing. Because of the scarcity of materials and the difficulty of making physical copies during lockdown, most of the zines Marcopoulos made between 2020 and 2021 were virtual, sent out as PDFs to a short list of friends and reproduced here for the first time.

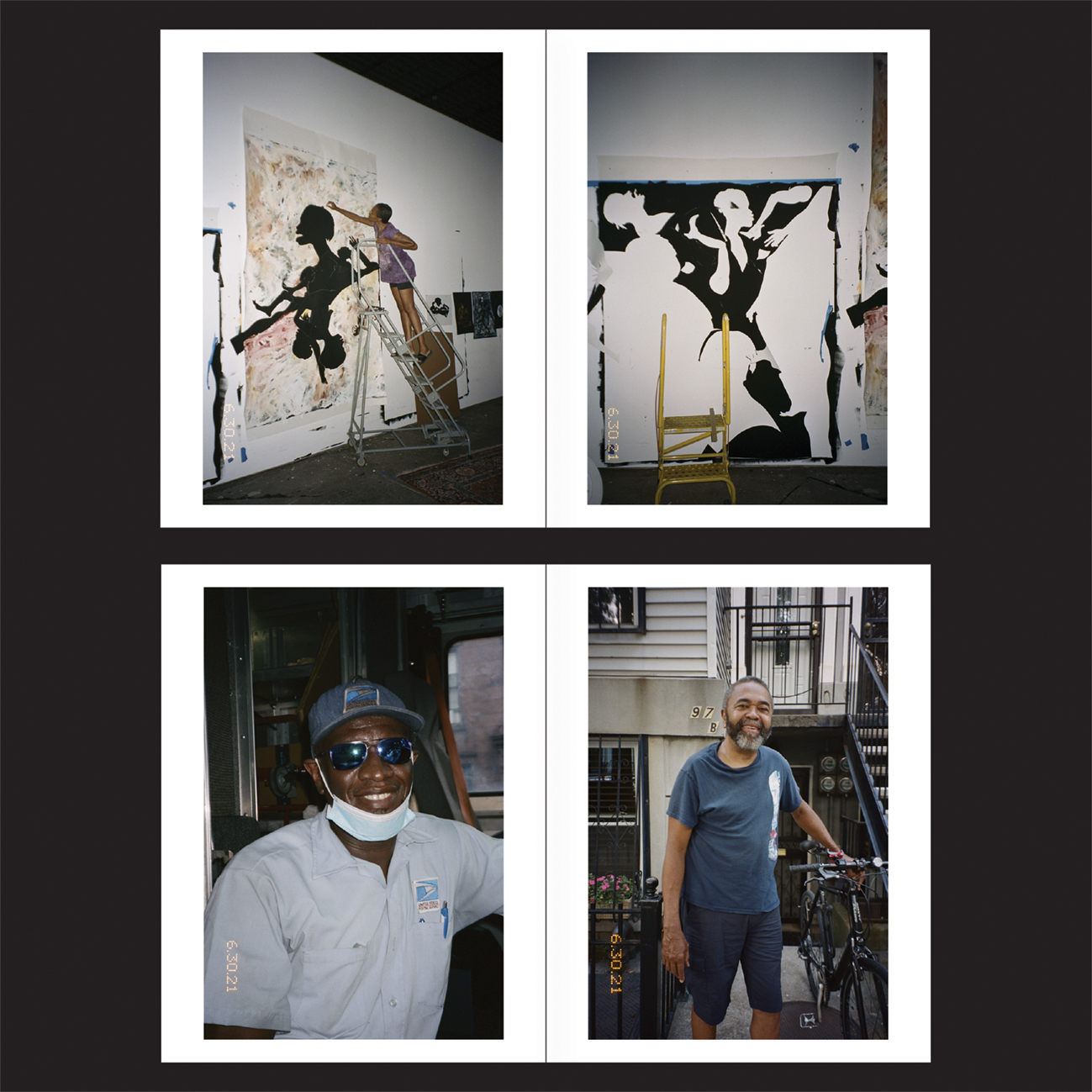

If Marcopoulos saw compiling and sending the PDFs as “a kind of personal letter-writing practice,” their content is not so different from the printed zines that preceded them. Working in color and in black and white, with simple point-and-shoot cameras and no pretense of mastery, he tends to make snapshots: tossed-off, time-stamped images of friends, family, street scenes, landscapes, the front page of the Times, landmarks, graffiti. Zine by zine, there’s no apparent narrative, no momentum. They’re scrapbooks, raw information: a life in pieces, some of which we recognize. Kara Walker, Marcopoulos’s partner (Zines is dedicated to her), crops up regularly, often in the process of making art. Here’s Hilton Als in a barber chair, Jay-Z on the street, and Stanley Whitney in his studio. But most of Marcopoulos’s subjects are people we don’t know, Brooklyn neighbors, skateboard buddies, passers-by. “Exchange is part of my practice,” Marcopoulos says. “[A piece] is really only finished if it’s circulating outside of yourself and there’s a viewer involved. Because the viewer finishes the work.” But the viewer can’t begin to bring that work to a close. Presented as one continuous scroll, Zines might stop on page 336, but it never really comes to an end.

The snapshot aesthetic Guido Guidi deploys in Di sguincio, 1969-81 (MACK) is classic by comparison to Marcopoulos’s. Although both photographers focus on the incidental and the everyday, in this body of early work, Guidi deliberately derails the matter-of-fact with comic, confounding, and sometimes poetic results. Nearly all his pictures here were taken without looking through the lens or making any attempt to frame or focus on his subjects. (Di sguincio means seeing things at a slant.) People are seen in horizontal slices, usually in rude close-up and brutally cropped. (In a conversation at the end of the book, Guidi acknowledges Mark Cohen and Lee Friedlander as influences.) But, perhaps because everyone seems to be in on the joke (what Guidi calls his “playful teasing”) and many are laughing, the mood is buoyant. And the pictures are great – completely unpretentious and oddly ingratiating. “I was interested…in exploiting the immediacy of photography,” Guidi says. “Each photograph is a note or a kind of scribble that bears witness to the act of photographing and simultaneously to the reaction to being photographed.”

The collaboration of Lee Friedlander and filmmaker Joel Coen is being covered as an exhibition elsewhere in this issue, but I wanted to make note of the book, Lee Friedlander Framed by Joel Coen (Fraenkel). Friedlander is a notoriously prolific book maker (one dealer is offering what it describes as “a complete collection” of 83 titles for $225,000), so one more hardly seems notable or necessary. But he has not always been his own best editor; even if he often seems incapable of a bad picture, his exhibitions and books are often grossly overstuffed. So the prospect of Coen taking charge and reigning things in was exciting. No question: their sensibilities are cleverly matched. But it wasn’t until I saw the exhibition (at Luhring Augustine through July 28) that I really appreciated the book, which struck me as choppy and predictable on the first pass. The same sequence flowed on the gallery wall, where it didn’t feel too dependent on greatest-hits images. Going back to the book with the show in mind, it all clicked. High expectations are often the worst thing to bring to any project, but sometimes they’re rewarded.