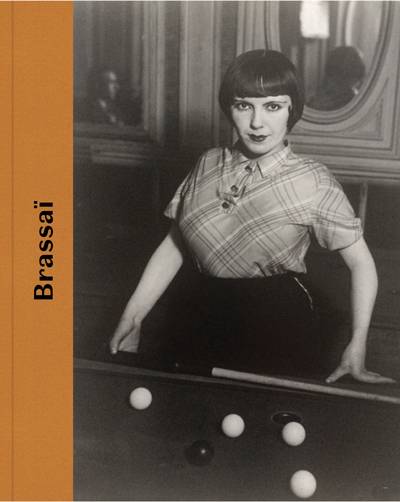

They may have nothing else in common, but three big new monographs give fuller, more in-depth views of their already well-known subjects than we’ve had before. Brassaï (Fundación MAPFRE), the catalogue for a retrospective exhibition that goes to SFMOMA in November, is, on first glance, the most familiar of the three. Although there are a number of previously unseen cityscapes and foreign views, we’ve seen most of these pictures of Parisian nightlife, with its thugs, swells, and bar girls, before. What’s new and immensely valuable is the supporting material, including meticulously researched, richly illustrated essays by Peter Galassi and Stuart Alexander, and a welcome emphasis on Brassaï’s work in the illustrated press; one section reproduces his pages in the avant-garde journal Minotaure. Joel Meyerowitz takes the retrospective into his own hands in Where I Find Myself (Laurence King), narrating his history in reverse by starting with the most recent work and going backward. In a career largely defined by color street work, there have been countless zigs and zags – into portraiture, reportage, black and white, the sublime seascapes of the Provincetown Bay/Sky series, and the devastation of Ground Zero. At least half the pictures here look new or newly contextualized; what connects them is Meyerowitz’s drive to witness the world, to give it shape. Early on, to overcome his shyness, he would photograph at parades, all but unnoticed by the throngs. “I could slip in under their gaze,” he writes, “like a plane flying too low to be picked up by radar. I would get so close I could hear them breathing.” Sally Mann’s A Thousand Crossings (Abrams) proceeds more or less chronologically through some 40 years of work, but time is difficult to pin down here. The catalogue for a traveling exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., through May 28 (see Sally Mann: Southern Discomfort, page 30), Crossings folds Mann’s work with her immediate family into what is essentially a book about the South at its most haunted and haunting. Impressionistic landscapes, some made on Civil War battlefields, dominate. Mann gives history palpable presence; essays by Hilton Als, Malcolm Daniels, and the exhibition’s curators, Sarah Greenough and Sarah Kennel, put it all in perspective.

Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger, Swiss photographers who met in Zurich art school, delve into a different sort of history in Double Take (Thames & Hudson) – the history of their own medium. Working in the studio with ordinary materials (cotton wool, transparent paper, feathers), they re-create famous photographs, rendering two-dimensional images in three dimensions, as if returning to the moment the picture was first made, but at tabletop scale. Their source material is, for the most part, immediately recognizable: the explosion of the Hindenburg, Buzz Aldrin’s footprint on the moon, Harold Edgerton’s milk splash, Robert Capa’s falling soldier. Their reconstructions are painstaking, often involving research into the original site or circumstance; they think of themselves as working “like forensic detectives.” And the results, in miniaturized scale, are astonishing. But their final photographs are not duplicates of the iconic originals – they’re pictures of the messy, improvisatory process of re-creating them without Photoshop. That moonwalk footprint was made on a square of what looks like cement dust with a slatted piece of wood, left on the floor nearby along with some red marking pens, a spoon, and a dustpan. William Eggleston’s bare bulb on a red ceiling hangs only a few feet above a floor scattered with the debris of its construction, the “room” it’s in nothing but a plasterboard corner propped up with a tripod. “We want to activate the viewer,” Sonderegger says, and engaging us in the process brings photographic history back to something like life.