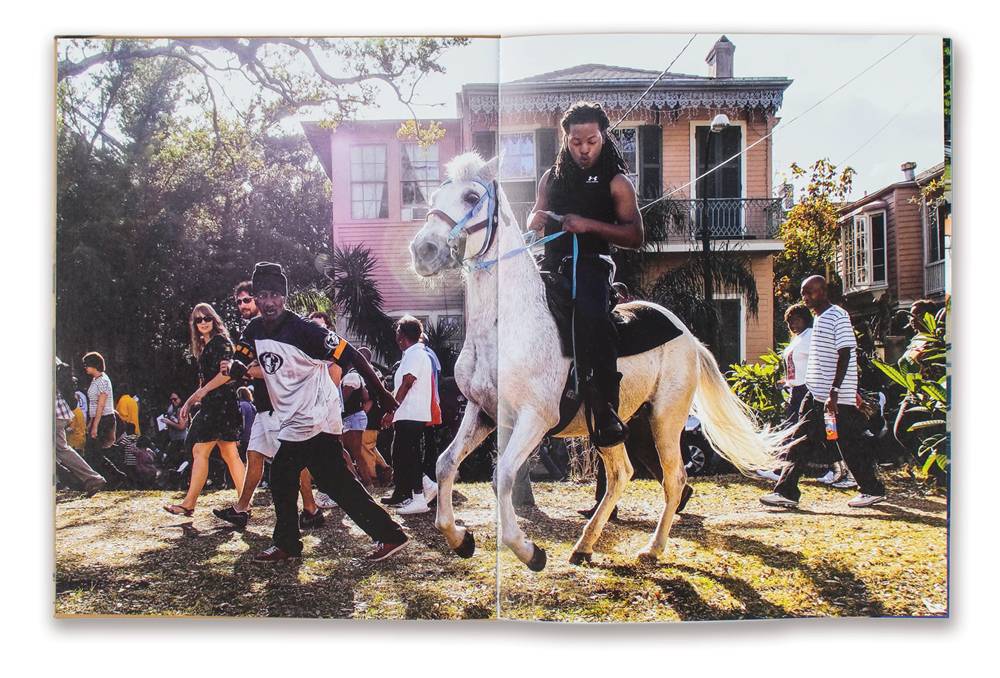

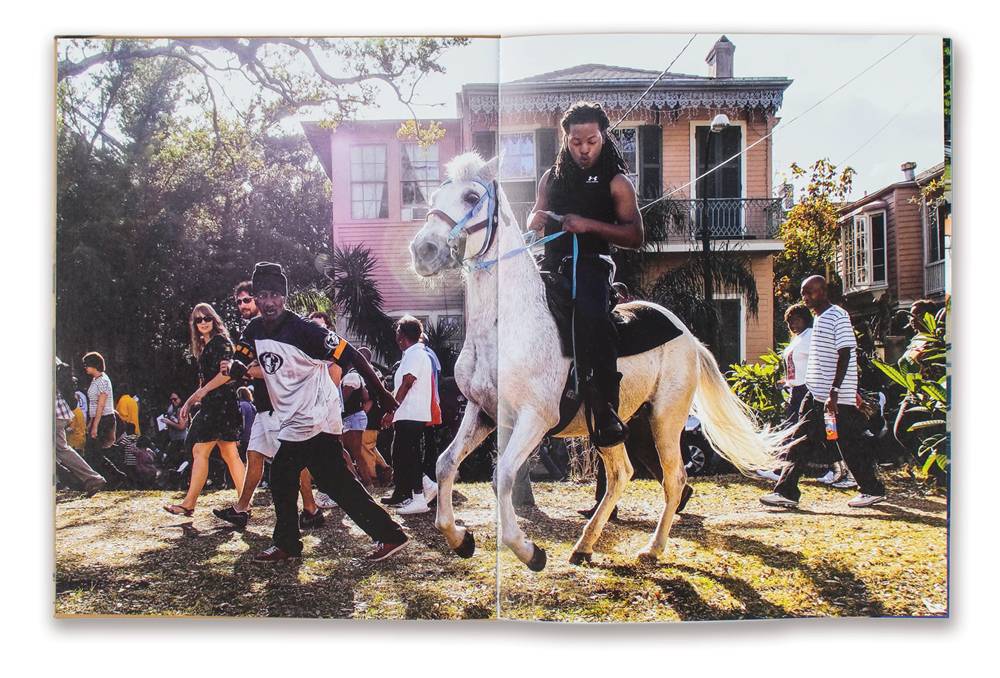

Peter van Agtmael’s last book, the widely celebrated Disco Night Sept. 11 (2014), shuffled between work the Magnum photographer made while embedded with troops in Afghanistan and Iraq and his equally engaged reportage from the home front. With captions that sometimes filled a page, he provided a running commentary that, in the words of his introduction, tried to make sense of “all the death and confusion and isolation and impotence these pictures represent.” His new book, Buzzing at the Sill (Kehrer), finds van Agtmael back in the States, where he can’t entirely shake the war or the death, confusion, etc. that continue to haunt the work. His texts are fewer but no less pointed or poignant. Conscious of his role as witness and journalist, he probes his youthful obsession with images of war at its most horrific, confesses “a deep wariness of humanity,” and questions his ethics: “There’s a great beauty but also a terrible presumption in taking the image of someone else and shaping it around one’s own version of reality.” Presumption comes with the territory, but beauty is hard won, and never a given, so when van Agtmael nails it again and again, in the most unexpected circumstances, it’s pretty remarkable. He photographs the American scene as if he’s rediscovering it, zeroing in on the occasional narrative (including murder and suicide in one African-American family in Detroit), but wide open and avid for all the facets of the bigger picture, whether it’s a white-robed Klan member emerging from the dark Maryland woods or the engagement party of two resettled Syrian refugees in Aurora, Illinois. Disco Night was traumatic – an alarm that never shut off. Buzzing, though just as tightly wound, suggests that there’s something to be said for humanity after all.

Richard Mosse, another photographer whose work is grounded in current events, is best known for a series he made in the Congo using outdated infrared film that turned green foliage bright pink and militarized landscapes into Fauvist fantasias. Mosse used another sort of technology for the images in Incoming (Mack), a solid brick of a book that offers a fragmented, hallucinatory view of the refugee crisis in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Mosse made the pictures with a military device used primarily for surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting that he adapted for digital-image capture. Its thermographic sensors allowed him to “see” people more than 30 miles away in some detail but only as heat generators, so features blur and melt. Although their circumstances are all too human, people look like phantoms or sci-fi aliens. That eerie effect is underlined by the colorlessness of the images, reproduced here in a soft-focus black and white that resembles platinum and shimmers with a silvery gloss on the book’s pages. Because these refugees, soldiers, and aid workers are unaware of the “camera” that captures them in close up, Mosse calls the results “stolen intimacy,” and in his text here, he acknowledges the “aesthetic violence” his device does. But he also identifies with his subjects: “We are portrayed as vulnerable organisms, corporeally incandescent, our mortality foregrounded.” It’s impossible not to feel like a spy, an intruder in these dramas of flight, rescue, and confinement, whether it’s the chaos of a boat landing or the sterility of a temporary camp. But if our intimacy is unearned, it’s not casual or easily shaken off. Mosse overwhelms us with images that flicker past like a film montage, accumulating a terrible, marvelous weight and power. So many lives lost and in limbo; a spectacle of desperation and frustration that builds to the repeated and increasingly zoomed-in image of a vehicle so overloaded with people and bundles it looks like the end of the world – or the beginning of a new one.