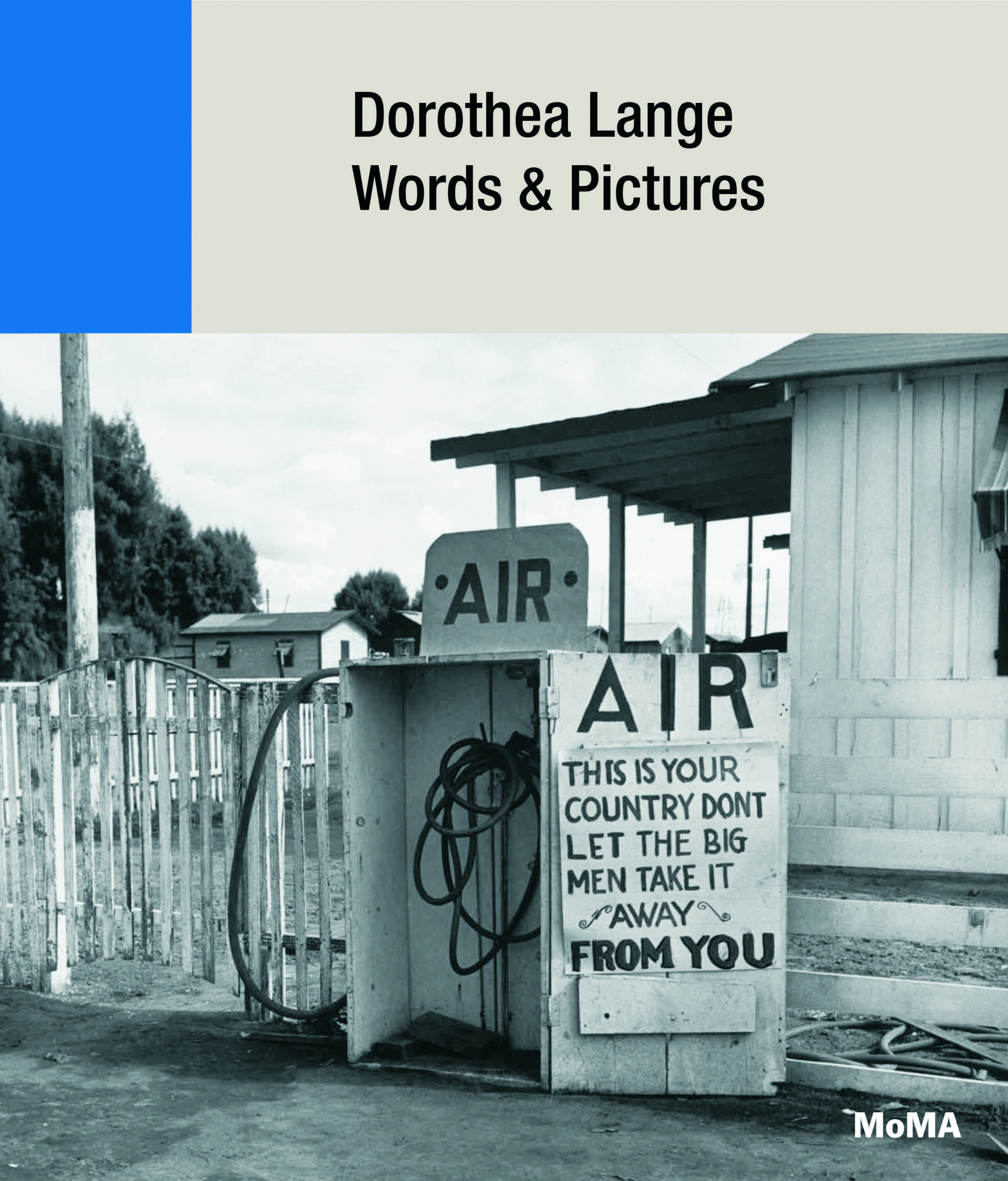

“I’m trying here to say something about the despised, the defeated, the alienated. About death and disaster. About the wounded, the crippled, the helpless, the rootless, the dislocated. About duress and trouble. About finality. About the last ditch.” No one could sum up Dorothea Lange’s achievement more trenchantly or more forcefully than the photographer herself in the wall text for what would become a posthumous exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1966. (The show opened in January; she died in October 1965, at 70.) Lange’s intentions could not have been more evident in her work. She saw clearly and concisely, without sentiment or polemics, but her pictures never feel detached or merely reportorial. Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures (MoMA), the catalogue to Sarah Meister’s exhibition (on view through May 9), reminds us of their enduring impact and importance at a time when Lange’s concerns couldn’t be more urgent. The book, which focuses on Lange in print, opens with a quote from Francis Bacon that hung on Lange’s studio door: “The contemplation of things as they are, without substitution or imposture, without error or confusion, is in itself a nobler thing than a whole harvest of invention.” With that in mind, Lange went out into a world in shambles and gave it shape. “Bad as it is,” she said, “the world is potentially full of good photographs. But to be good, photographs have to be full of the world.” At a time when exhibitions were rare, Meister looks at how those photographs were published and distributed, spurred by a mass-market surge in visual literacy. The work Lange did with the Resettlement Administration, the New Deal agency later known as the Farm Security Administration, was widely circulated by the government and appeared in Life, Look, US Camera, and other popular illustrated magazines. Those and other photographs of the Dust Bowl and its human toll were collected in An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, published in 1939, but Lange’s pictures had already become iconic. In a separate publication, part of MoMA’s One on One series, Meister details the history of the 1936 photograph that came to be known as “Migrant Mother,” summarized succinctly in Words & Pictures. Other key images get individual attention from a lineup of guest artists and writers, including Sandra Phillips, Julie Ault, Sam Contis, Rebecca Solnit, Wendy Red Star, and Sally Mann. But the book is most interesting when it looks beyond the famous photographs and shows us less familiar work in its original printed context.

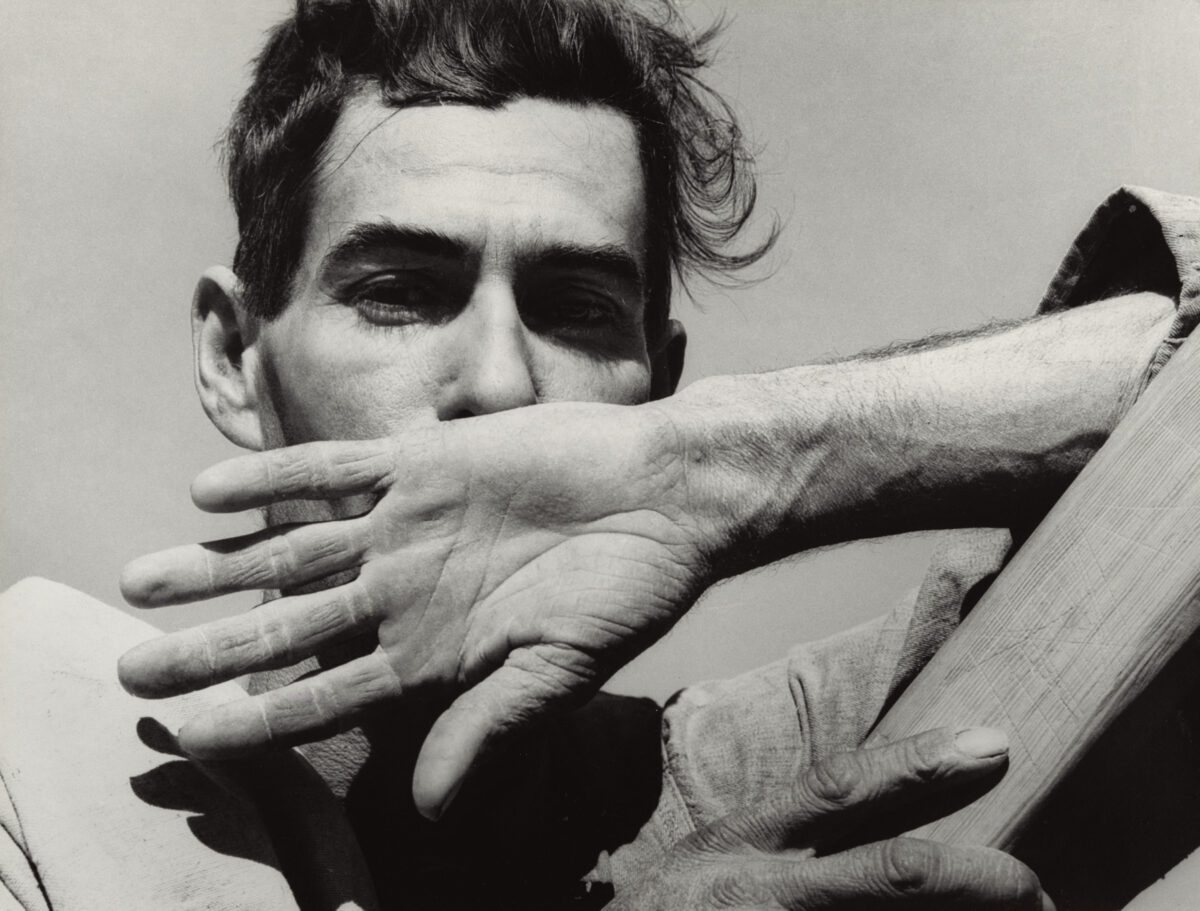

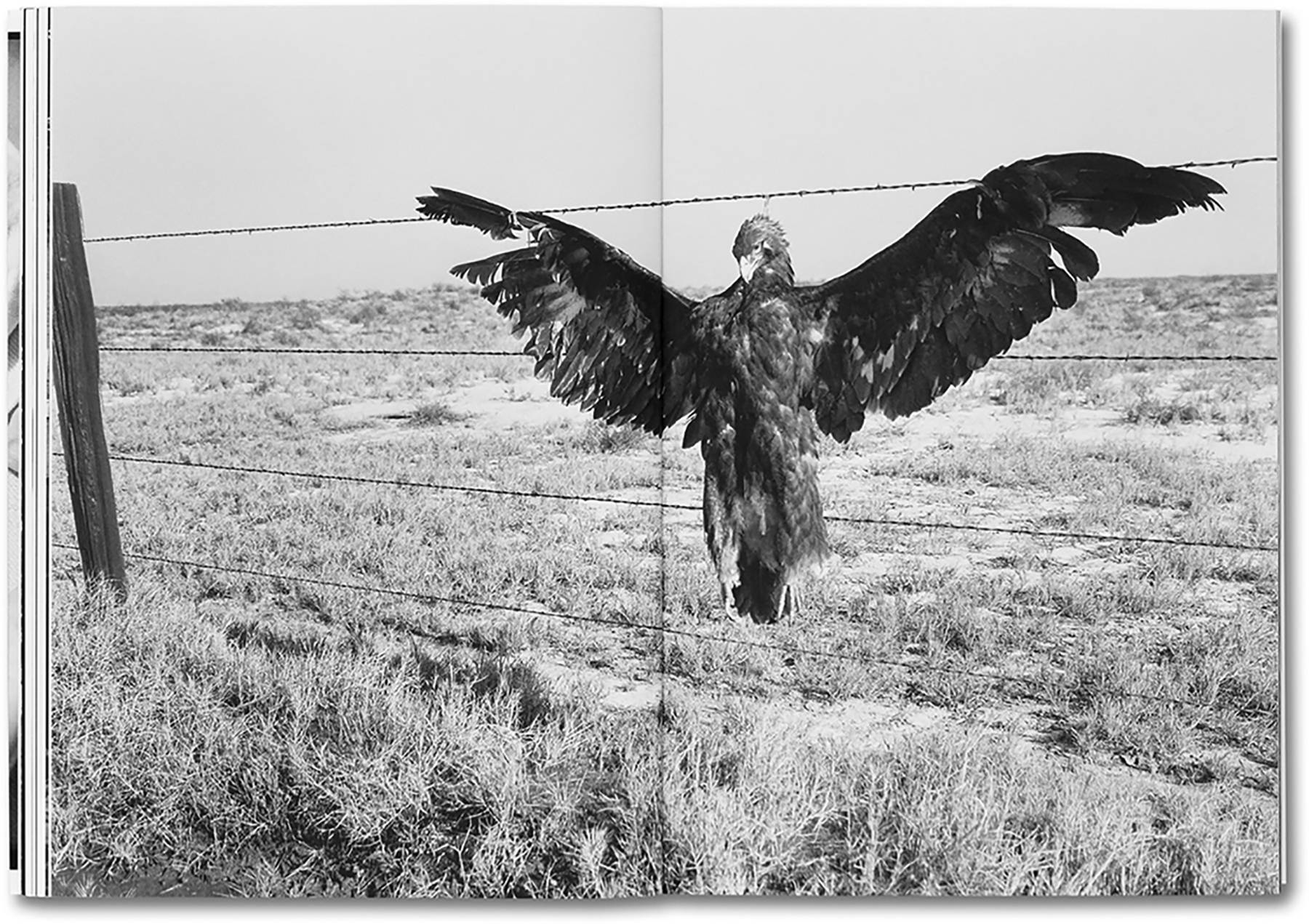

Excited by what she felt was “an unexpected kinship” and “a shared sensibility,” the Oakland-based photographer Sam Contis had been poring through the Lange archive at the Oakland Museum of California for some time when Meister invited her to be a contributor to Words & Pictures. She has no more space than the other essayists in its pages, but she takes much more in Day Sleeper (MACK), a book of more than 60 Lange photographs, nearly all previously unseen, chosen and sequenced to underline that shared sensibility. This would seem self-serving if the result wasn’t so revelatory, smart, and exciting. Encouraged when she read that Lange liked the idea of grouping images to suggest “relationships, equivalents, progressions, contradictions,” Contis channels her energy without disturbing the restrained, contemplative mood of much of the work. But she skews it to intimate moments – to gestures, tangents, and fragmented bodies that echo the pictures in her exceptional 2017 book, Deep Springs. Contis has installed some of this material at MoMA, but the fullest expression of this brilliant Artist’s Choice exercise is here between (soft) covers, with an imageof Lange’s sun-struck, sleeping son – angelic and aglow – on the front.