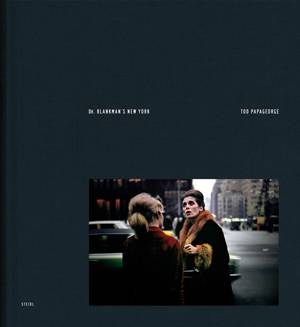

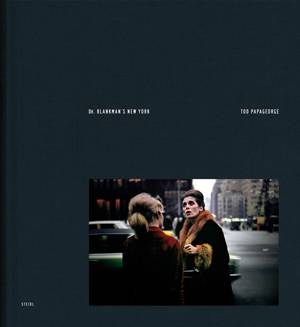

Dr. Blankman’s New York (Steidl), a collection of color photographs Tod Papageorge made in the city in 1966 and ’67, is an excellent place to kick off a roundup of street work. According to David Campany’s afterword, Papageorge was 25 that first year and new in town, but his work is strikingly confident and as subtle as it is vivid, always alert to the moment and the mood of the street. The book’s title comes from an optometrist’s sign in the window of the opening image – the first of many storefronts Campany traces back to Atget and Walker Evans and, thanks to a grocery-store’s row of Brillo boxes, forward to Warhol. Given the year, a Pop Art sensibility is all but inevitable, so it’s no surprise that Papageorge zeroes in on the sorts of signs, products, and displays that also excited Rosenquist and Rauschenberg. But Campany identifies an even more crucial quality here. “Papageorge seems to have intuited that, at its core, depiction is an affectionate art,” he writes, pointing to the “empathy and fascination” in the work. That sensitivity doesn’t keep Papageorge from making sharp, revealing observations of the passing scene, but when people are his subject, he’s never savage or blasé. Several lines from a poem Papageorge wrote in 1967 make that point: “I walk within a soft, electric storm/ brushed and charged by the dense, thrumming air,/ seeing things…”

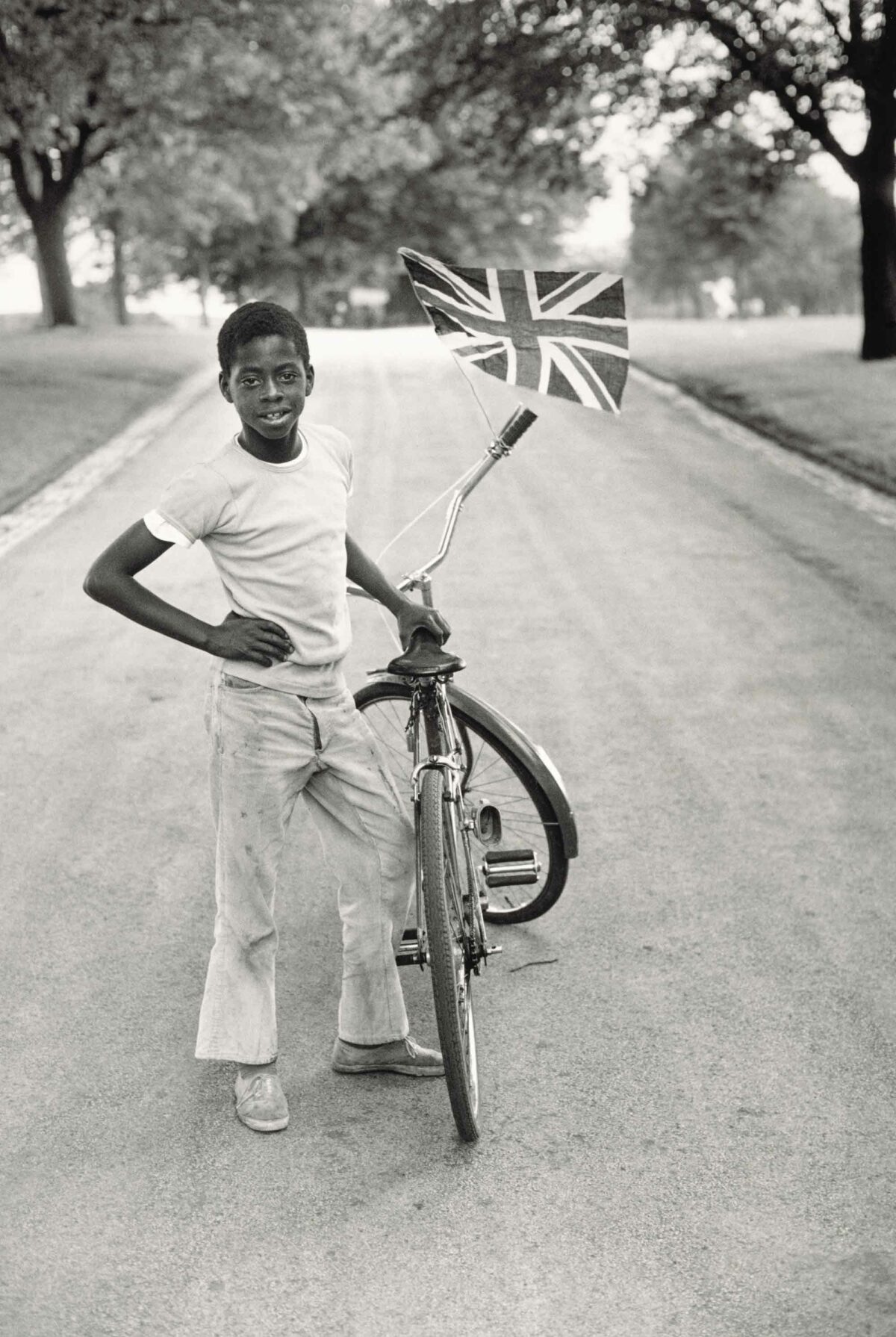

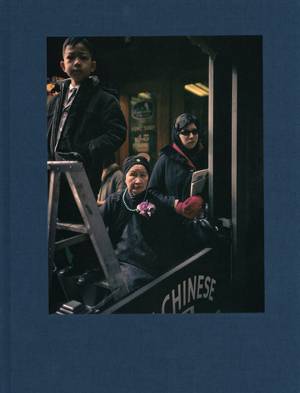

On the evidence of her pitch-perfect New York (Steidl), Evelyn Hofer shared some of that same thrumming air just a few years before – and nearly a decade after – Papageorge did. The color and black-and-white pictures in her book were taken mostly in the mid-’60s and mid-’70s; the most recent is from 1981. Hofer’s cityscapes recall Berenice Abbott’s and her street work has a similar formality and precision. Her subjects aren’t seen in passing; they’re arrested and posed, with occasional echoes of August Sander or Irving Penn’s “Small Trades” workers. What’s distinctly Hofer is warmth – a generosity of spirit that’s wide open to New York’s diversity of class and color. The owner of an animal funeral home looks like he belongs in a Diane Arbus photograph, but Hofer is more often drawn to less italicized subjects: a trio of women outside a Harlem church, a gaggle of workers in the Garment District, a vendor in Chinatown, a teenager on his bike. The affection Campany attributes to Papageorge is even more apparent in Hofer’s work. She loves New York and that (strictly unsentimental) sentiment is infectious.

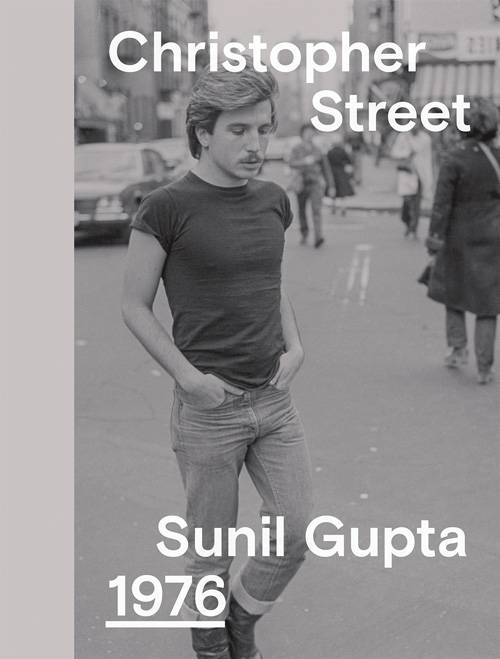

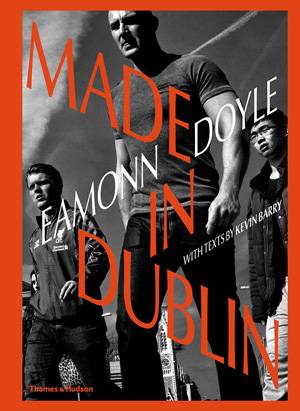

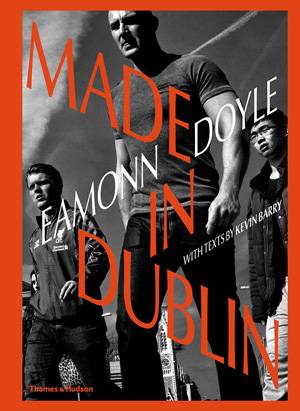

If only because all the work was made since 2011, Eamon Doyle’s Made in Dublin (Thames & Hudson) has an entirely different vibe: hectic, brusque, on edge – at once exhilarating and exhausting. A design-driven knockout built on clipped, cinematic montages, the book compiles three earlier Doyle volumes in one headlong rush. Mark Cohen is an obvious influence, as are Paul Graham and Bruce Gilden. But if Doyle doesn’t connect with the people in his pictures as viscerally or emotionally as those photographers do – he tends to skitter off his subjects’ surfaces – he’s hard to beat when it comes to graphic impact. He channels the energy of the Dublin street like a live wire. Handle at your own risk. It’s no slight to call Sunil Gupta’s Christopher Street 1976 (Stanley/Barker) a great book of fashion photographs. “It was the heady days after Stonewall and before AIDS,” Gupta writes, and gay men were out on the Village’s main artery in clothes that identified them as members of a newly empowered tribe – one that defined masculinity on its own terms. Gay Liberation can’t be pinned to a pair of faded 501s and a bomber jacket, but Gupta’s pictures of the way we were are poignant reminders of the power of self-invention.