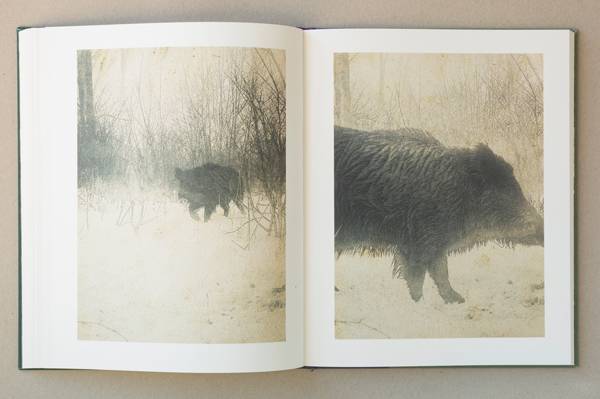

According to his website, the British photographer Stephen Gill has published 23 books since 2004 – a remarkable body of work, much of it made in the East London area of Hackney Wick, where industrial ruins meet woodlands and waterways. Gill’s latest book, Night Procession (Nobody), stakes out new territory in a remote rural area of southeastern Sweden, where he’s lived since 2014. Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose six-volume autobiographical novel My Struggle has made him a literary star, lives in a village nearby and has written the book’s only text, included as a stitch-bound insert. Knausgaard heard that Gill had set up a motion-activated camera in the woods to snap pictures of the deer, owls, hawks, and wild boar that came out at night, but he wasn’t prepared for the extraordinary results. His description of the work helps locate it in his own corner of the Swedish landscape, but, he writes, the place Gill’s photographs evoke is “the very opposite of the local and the particular.” It’s the forest of our imagination: “The wild, the dark, the free, the boundless, the mysterious, the alien, the humanless, the primitive. Fairy tales, myths, the Romantic.” This is a lot to pile on a little book, but Gill earns every word. From the beginning, his work has been low-tech and process-driven, incorporating elements of chance – things he could not control. Setting his camera up to record when he was nowhere around leaves the photographs open to all kinds of tilts, blurs, and revelations: a fox staring at his reflection in a stream or a ghostly rabbit, bounding right at us. Knausgaard calls this “the world inside the world” – the world that exists without us, despite us. Even when we can’t quite make it out, it’s fascinating. Not all of Gill’s photographs here were taken automatically, but they all have a sense of wonder – like seeing something for the first time – with terror close behind.

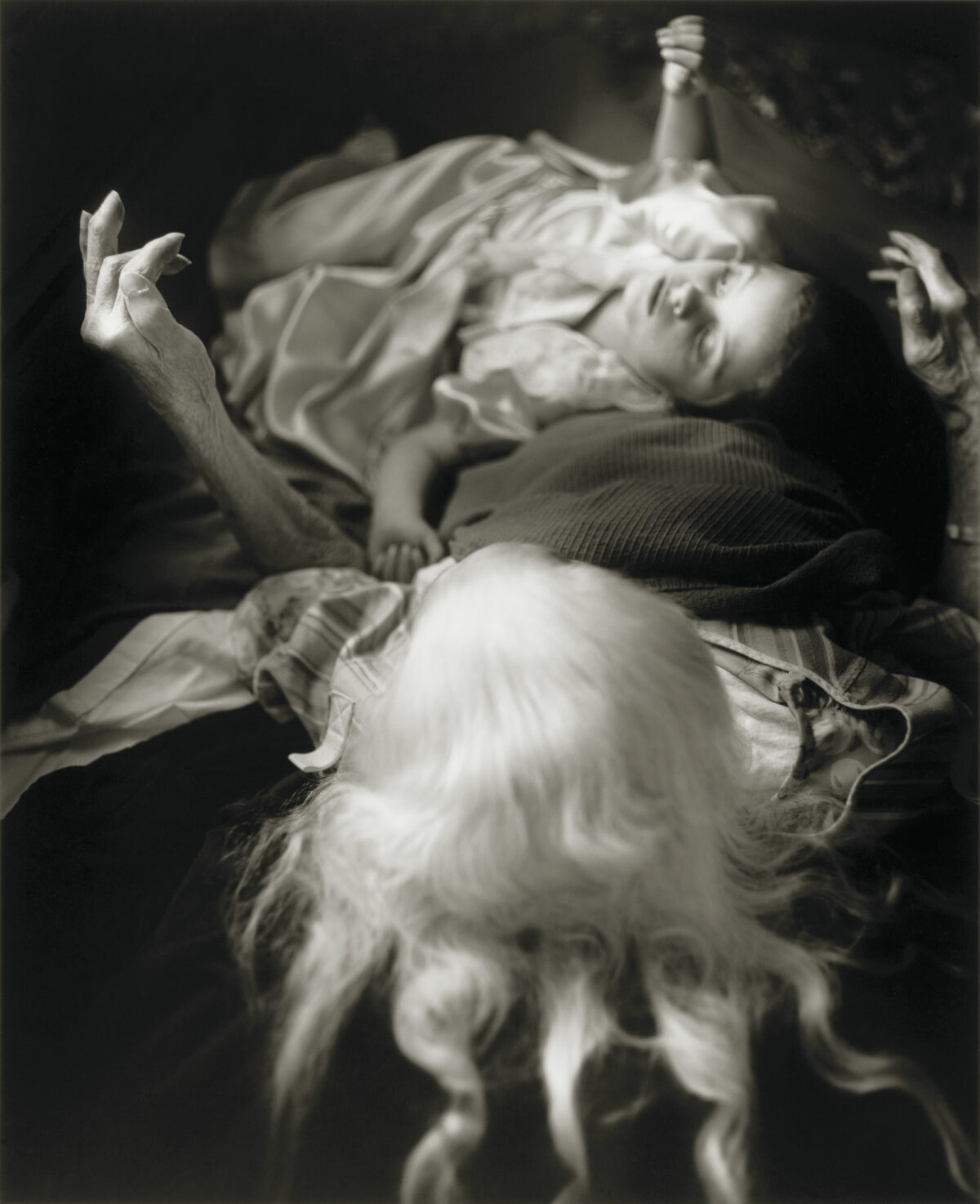

One of the books that really opened my eyes to photography – its range, depth, and infinite possibilities – was collector Sam Wagstaff’s A Book of Photographs (1978). Jack Shear takes Wagstaff as a model for Borrowed Light (DelMonico/Prestel), a book of the photographs he and curator Ian Berry culled from his collection as a gift to the Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College. “This is a book about pleasure, the pleasure of looking and the pleasure of seeing,” wrote Wagstaff, a quote that serves as the epigraph to Borrowed Light, but could just as easily apply to the Mexican collector Pedro Slim’s recent book, The Most Beautiful Part (Museo de Arte Moderna). Both Shear and Slim are photographers themselves, both are gay, and both have wide-ranging and highly individual tastes and a genuine appreciation of the power of eroticism. Their books complement one another, with plenty in common when it comes to photographers (Peter Hujar, John O’Reilly, Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, Danny Lyon, and Bruce Weber, for instance) and only one repeated image. Taking up the subject of the body, Slim’s collection is more narrowly focused (and a lot sexier) than Shear’s, but hardly constricted and far from predictable. Slim’s openness to gender fluidity puts masculinity and femininity in perspective. Shear, though just as even-handed, tends to skew toward images of men, including a number of portraits and self-portraits of writers and artists, from Walt Whitman to Ed Ruscha. With nearly 350 photographs and almost no text, Shear’s book covers a lot of historic and psychic ground, and his juxtapositions are always striking: Weegee faces McDermott & McGough, Julia Margaret Cameron speaks to Edward Weston. With a wealth of little-known and anonymous images, this is not a horde of trophies. In the Wagstaff mold, it’s a deeply personal collection and its strength is in its shrewd idiosyncrasy.