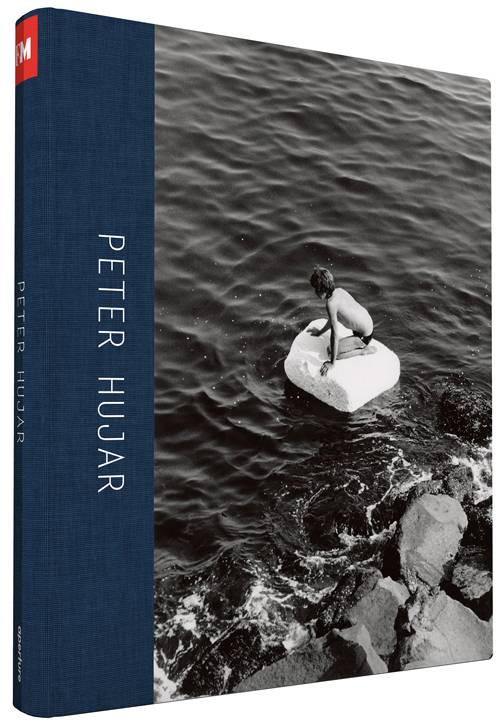

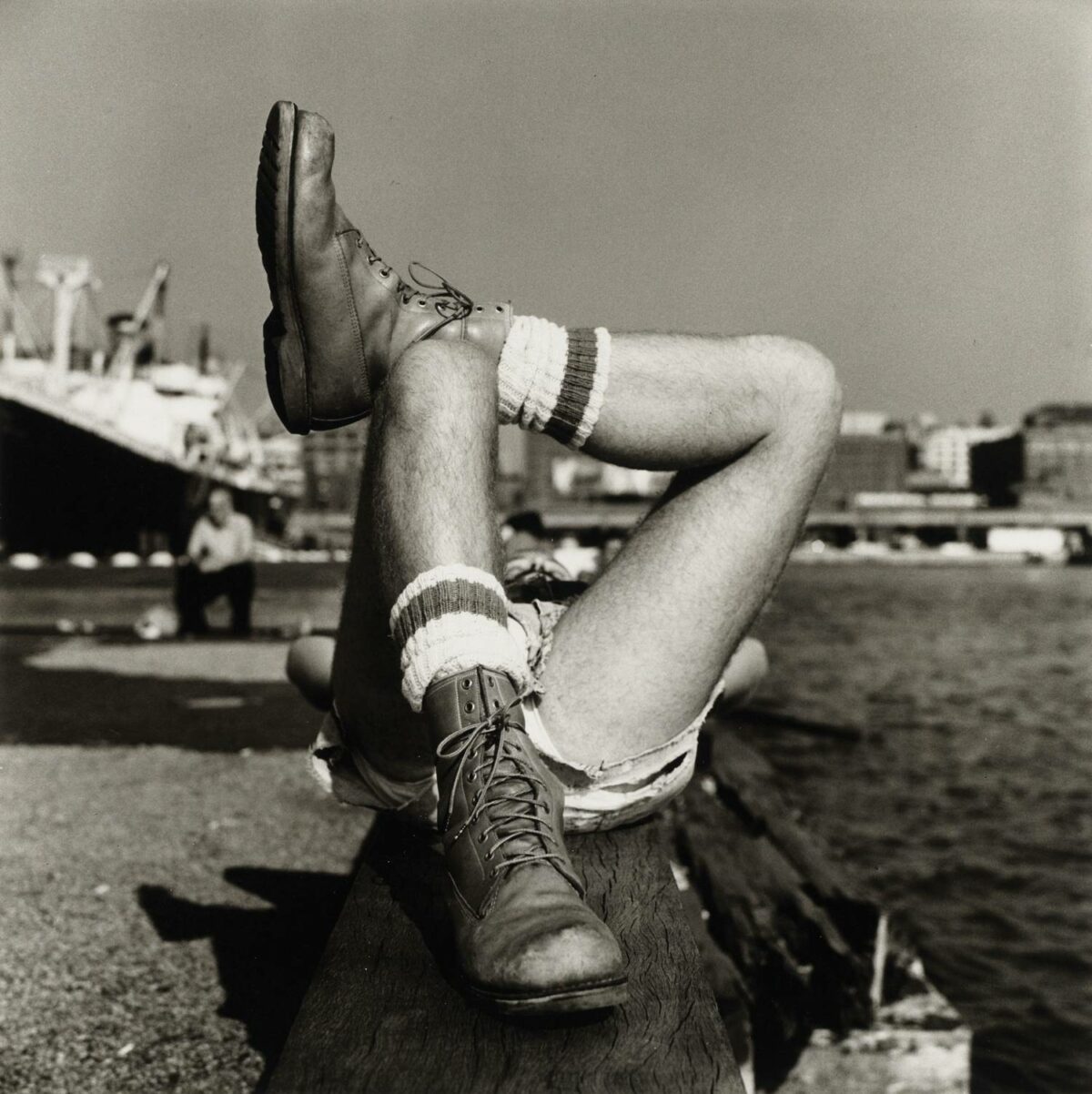

Peter Hujar was a friend, a great friend, so it’s gratifying to see his work getting the attention it rarely received in his lifetime (1934-1987). Peter Hujar: Speed of Life (Aperture/MAPFRE), the catalogue for an exhibition that arrives at the Morgan Library & Museum next January, is the most thorough and thoughtful re-evaluation of that work so far. Many of the 160 photographs here have not been published or exhibited before, and they’re framed by material from the Hujar estate that fleshes out a portrait of the artist with snapshots, contact sheets, tear sheets, and other ephemera. The Morgan’s Joel Smith, who organized the exhibition, contributes the smartly illustrated, meticulously researched opening essay and (with Martha Scott Burton) an obsessively detailed chronology that will surprise even the photographer’s closest friends. (On December 18, 1974, according to this rundown, Peter let me use his shower in exchange for a take-out Chinese dinner.) Both fill in biographical data that Hujar preferred to elide or embroider (he told one museum he was born in Hollywood, not Trenton) without losing sight of the queer downtown counterculture he helped to define but never wanted to be defined by. His sitters (all here) included William Burroughs and Peggy Lee, David Wojnarowicz and Louise Nevelson, Fran Lebowitz and Isaac Hayes, and a slew of genderfuck performers in and out of costume. His nudes were inevitably compared to Mapplethorpe’s, but they’re earthier, more soulful, and more affecting. “I want people to feel the picture and smell it,” Hujar said of the nudes, but that could apply to much of the work here, including pictures of dogs, skyscrapers, landscapes, crowds, a snake, a blanket, and a table full of Chinese food. If this complicates the image we have of Hujar, so much the better. By opening up the archive on the 30th anniversary of his death, Speed of Life presents a fuller picture and hints at more to come.

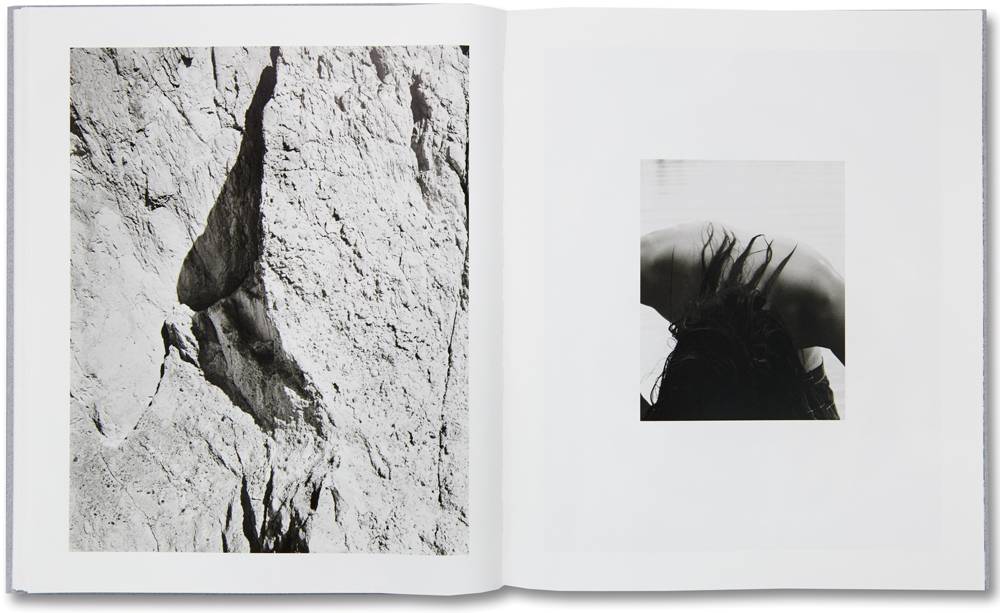

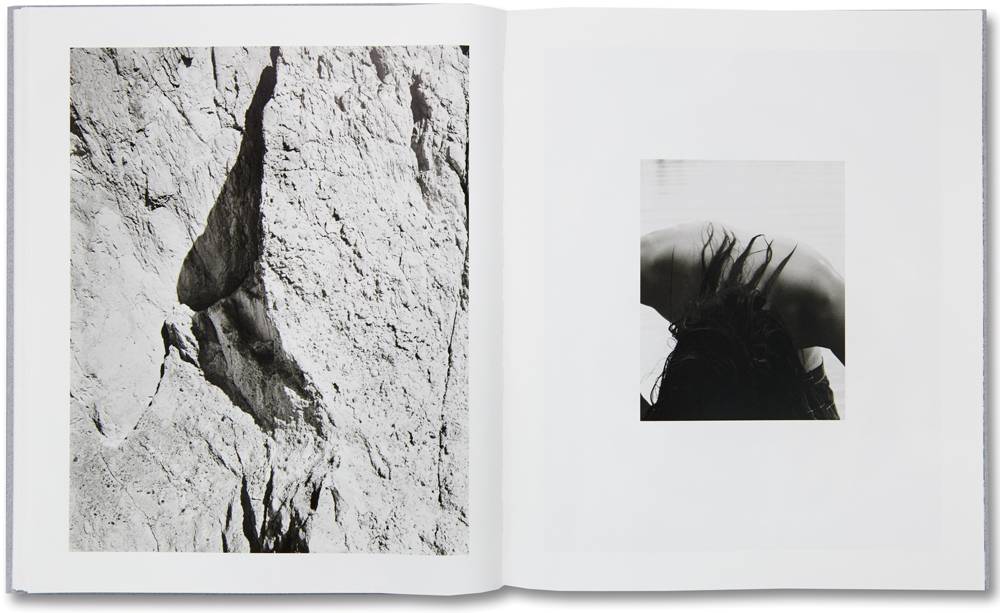

Like Collier Schorr and Justine Kurland, Sam Contis is a woman who photographs men with a probing sensitivity and remarkable subtlety, as if she’s wondering exactly what makes them tick and is determined to stick around and find out. That care and patience more than pays off in her first book, Deep Springs (MACK), made over five years at a small, isolated, all-male college in the California desert. With no text save for a brief endnote, the book is casual and impressionistic but far from random; pictures of the students, often engaged in the rugged manual labor that’s key to the college’s curriculum, alternate with panoramic landscapes, nature studies, still lifes, and vintage snapshots. Contis flirts with the myths of the American West – magnificence, manliness, freedom, grit – but she grounds her work in the bodies of young men, in flesh and bone. Maybe that’s why her pictures feel more like experiences than observations; Deep Springs isn’t a destination, it’s a journey.

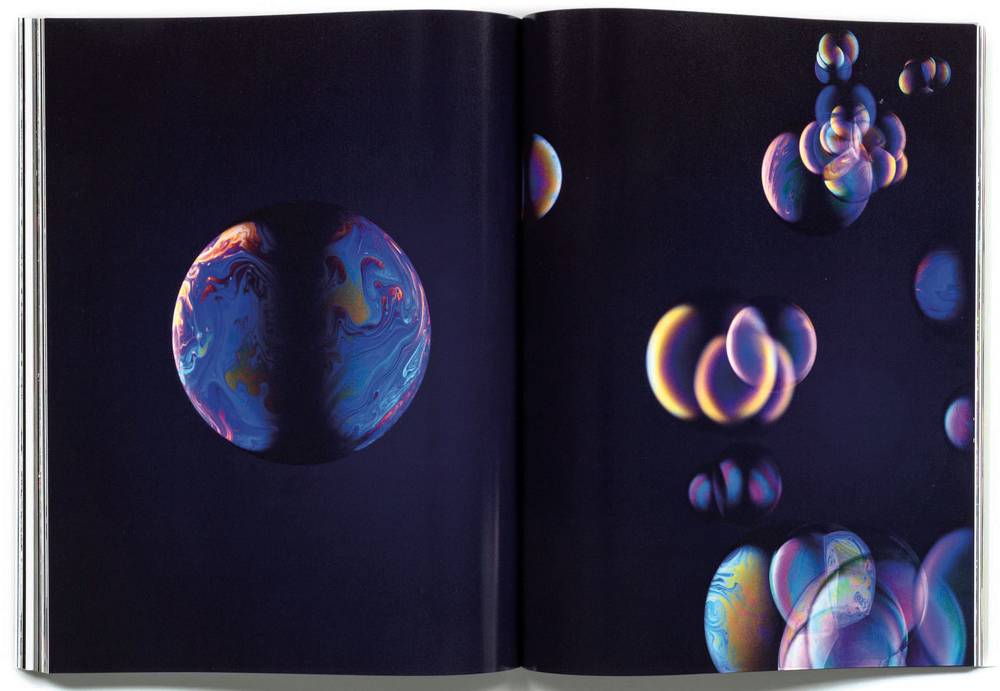

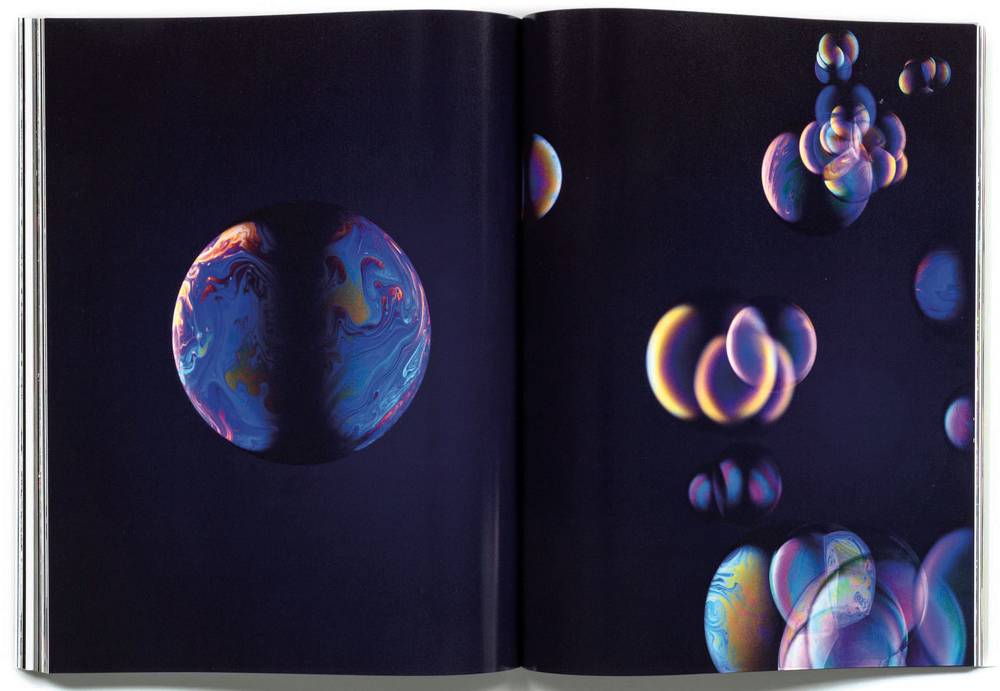

And now for something completely different: Mocafico Numéro (Steidl), a boxed set of six volumes devoted to the reliably, relentlessly inventive work Guido Mocafico has done for that French fashion monthly since 1999. Although Mocafico’s specialty is the sort of still life fashion magazines are obliged to feature (jewels, watches, perfume, make-up), his results are never routine, and he’s equally adept at landscape, architecture, and nature. This set of books is slick and much too much, but so dazzlingly encyclopedic it’s like dipping into a gorgeous reference book. Mocafico is famous for his close-up images of snakes coiled into the space of a magazine spread. Included here, those pictures have competition from spurting geysers, exploding volcanoes, hairy spiders, jellyfish, soap bubbles, and gems all but lost in the dust of torn-up vacuum-cleaner bags.