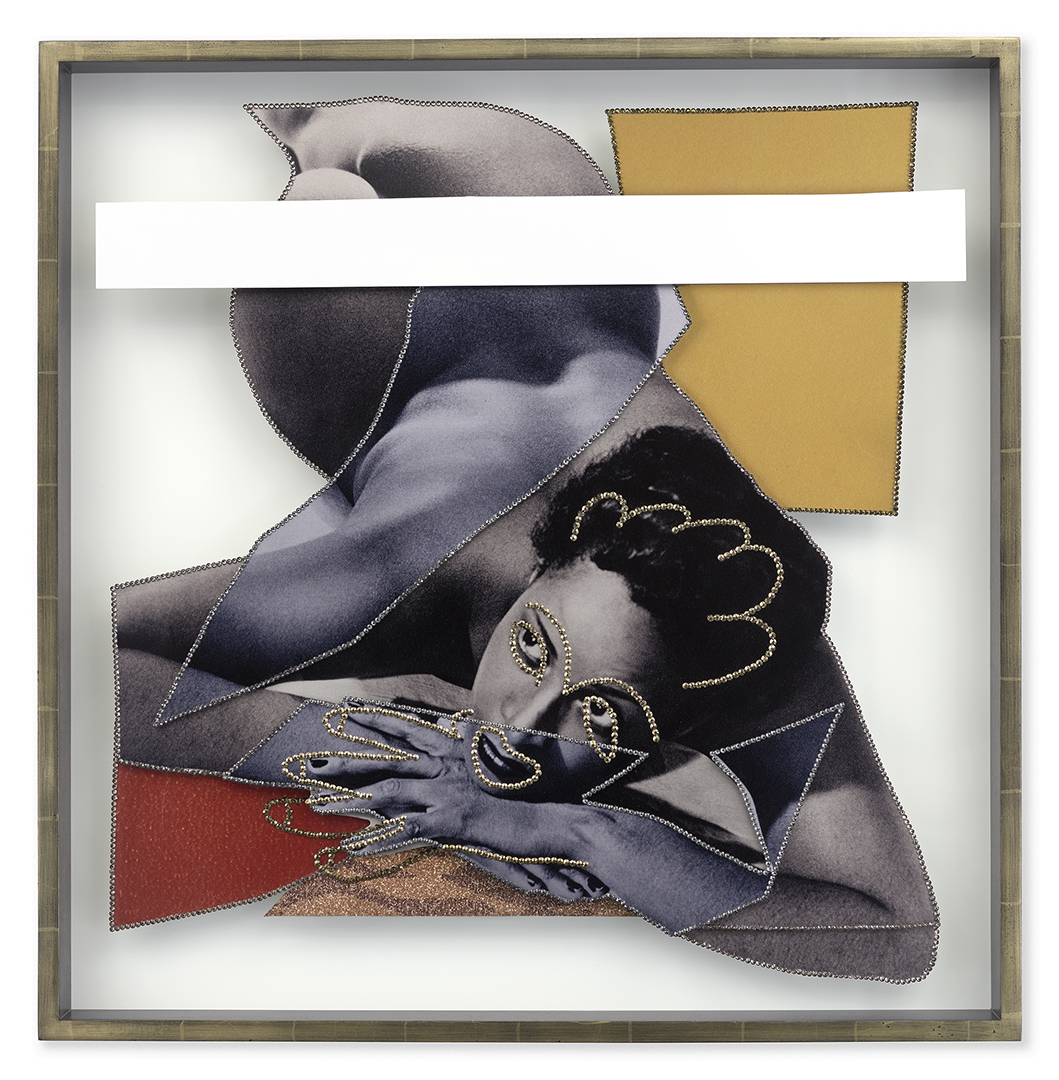

Carl Van Vechten, famous as a champion of the Harlem Renaissance, had published seven novels with Knopf by 1930, including the notorious Nigger Heaven, but his witty, satirical style wasn’t really suited to the radicalized 30s, and he put literature aside. By 1932, in a letter to his friend Langston Hughes, he announced that he had “become completely a photographer,” and he launched himself into a career as a portraitist. His influences were Steichen and Stieglitz; his subjects primarily artists, actors, writers, dancers, and other performers, many of them gay and nearly all members of his New York social circle. Fifty of those photographs are included in ‘O, Write My Name’: American Portraits, Harlem Heroes (Eakins Press), a handsomely produced book, based on a limited-edition portfolio first published in 1983, that focuses on key figures of the Renaissance (Hughes, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston) and the subsequent generation of what Darryl Pinckney calls, in his introduction, “Negro achievers, ambassadors of the black race.” Among this elite are James Baldwin, Bessie Smith, Jacob Lawrence, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ella Fitzgerald, and Joe Louis, but the portfolio’s original editor, Eakins Press founder Leslie George Katz, understood that Van Vechten saw beyond African American celebrity, so he included two tender portraits of women identified as “domestic workers,” one of whom was the photographer’s cook for more than 35 years. Van Vechten’s “admiration of his subjects was unambiguous,” Pinckney writes, speculating that “maybe he had that gay person’s sympathy for black Americans as outsiders.” It’s just as likely that Van Vechten saw his sitters as natural allies in the cultural avant-garde, and he gives each of them a similarly understated star treatment. Nearly all the portraits were made in his studio, with the subject seated before a draped or patterned fabric backdrop – a simple, easily improvised setting not unlike those used by countless small-town photographers or, to rather more sophisticated effect, by his contemporary Cecil Beaton. (From our perspective, the work looks like Man Ray as interpreted by Seydou Keita.) Within these confines, the pictures are formal and contemplative, rarely candid. In Ethel Waters’s words, quoted alongside her fine portrait here, Van Vechten’s subjects have “the truest dignity of man, the dignity of the undefeated.” With the exception of Lena Horne, photographed smiling and outdoors in 1941, there’s more gravity than vivacity here, but that’s entirely appropriate. Although his work is quiet and unpretentious, Van Vechten had his eye on history, American history, and you feel the weight of it here.

Thomas Ruff takes on another sort of history in Zeitungsfotos/Newspaper Photographs (Bookhorse), a compact brick of a book that reproduces 400 pictures culled from German newspapers between 1981 and 1991. Uncredited and uncaptioned, in grainy, low-contrast black and white, the photographs shuffle back and forth through time, from Mao to Gorbachev to Janis Joplin to Saddam Hussein, but return with pointed regularity to Hitler and the Third Reich. Although the sequence may not be random, it lurches about like a kid with ADD, seizing on the momentous, the enigmatic, and the absurd: protests, explosions, summit meetings, rocket launches, a Magritte painting, a baby carriage, a still from Breathless. Ruff has a long history with appropriated images, including the 2009 jpegs series of blown-up and pixilated news photos. Next to them, the clippings in Zeitungsfotos are relatively unmanipulated and undigested – a heavy meal. As raw, dumb data, they’re especially bewildering to anyone not steeped in recent German history, but you don’t need to identify all these politicians, bureaucrats, and criminals to know that Ruff’s edit of history is decidedly dark. Even the best old news is inevitably shadowed by death; here, it looms oppressively, turning this brilliant little book into a gaping black hole.