You won’t find Leo Goldstein in any of the dictionaries, encyclopedias, or guides to photographic history. Although one of his photographs is included in The Radical Camera (Yale University Press), the history of New York’s Photo League, his name never comes up. So a substantial, appealing new book of Goldstein’s work, East Harlem: The Postwar Years (powerHouse) is a genuine surprise. Little seen in his lifetime, Goldstein’s photographs were boxed up following his death, at the age of 71, in 1972, and only unpacked after the death of his wife, in 1996, when his son and daughter-in-law cleared out the family home and realized the importance of the work. Goldstein’s approach is solidly within the Photo League mold of concerned, left-leaning photojournalism. His influences were Paul Strand, Lewis Hine, and Berenice Abbott; he has obvious affinities with Walter Rosenblum and Helen Levitt, and his Spanish

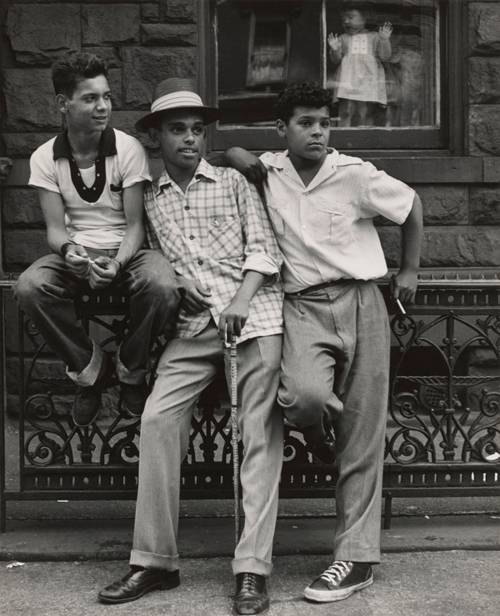

Harlem work anticipates Bruce Davidson’s darker, more intimately engaged East 100th Street. If he’d had more of a presence on the scene, Goldstein would have been a candidate for the group Jane Livingston dubbed the New York School, which included Saul Leiter, Lisette Model, Weegee, and Leon Levinstein. Impossible not to think of all these photographers when looking at Goldstein’s work, but, perhaps because he grew up for a time on these streets, there’s an intimacy, sympathy, and comfort here that feels unique. The earliest photographs were made in 1949 but nearly all the East Harlem work is from 1950, and despite the obvious poverty, it’s suffused with an aura of mid-century optimism. Even if that was only in the eye of the beholder, it gives Goldstein’s pictures a subtle warmth, a sense of camaraderie that’s all the more evident in the many pictures of people hanging out on stoops, as relaxed as if they were in their living rooms. They face the camera candidly, with little or no wariness or resentment, and Goldstein rewards them with portraits that are charming, compassionate, and among the period’s best (unintended, unself-conscious) fashion pictures.

Davide Sorrenti isn’t in any of those photography guides either. Just shy of 20 years old when he died in 1997, he was too young to have made much of an impact outside of his own charmed circle. But a book of the work he made between 1994 and his death, titled with his name and his graffiti tag, Davide Sorrenti ArgueSKE (Idea), proves the downtown legend was as talented as he was cool. Sorrenti grew up in a clan of fashion photographers, including his mother, Francesca, who edited the book; his brother Mario; and sister Vanina, and hung out with skateboarders and graffiti artists. His work draws on both influences, recalling Kids-era Larry Clark and vintage Nan Goldin by way of Ryan McGinley, Jack Pierson, and Corrine Day – a combination of wild-style spontaneity and romantic melancholy. When he wasn’t making self-portraits, Sorrenti’s pictures were mostly of friends and lovers – including the young model Jaime King (also, famously, a Goldin subject) – on the street, at home, and in bed. The mood is louche and laid back but highly charged – both erotic and narcotic. Sorrenti was deep inside what another generation thinks of as Youth Culture. It’s not his subject; it’s his life, and there’s not a false moment here. Working in color that’s luscious and bruised, Sorrenti made some of the best photographs of New York just before the turn of the millennium by focusing on his tribe: New York’s delinquents, strivers, and bohemians, the beautiful and the damned. Interspersed throughout, tributes by Jefferson Hack, Milla Jovovich, Edward Enninful, Harmony Korine, and others read like book-cover blurbs. They’re sincere but unnecessary; the photographs tell us all we need to know.